Read Delphi Works of Ford Madox Ford (Illustrated) Online

Authors: Ford Madox Ford

Delphi Works of Ford Madox Ford (Illustrated) (619 page)

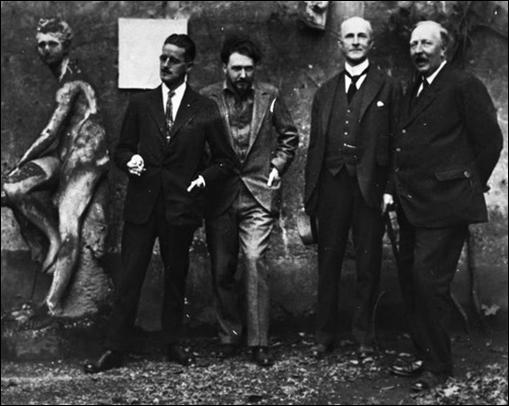

James Joyce, Ezra Pound, John Quinn and Ford Madox Ford in Paris, 1923

I DO not wish to apologize for this publication, but I wish to propitiate beforehand those who may object that I am putting out Collected Poems rather than a Selection, and I wish to make some speculations as to the differences between prose and verse as they are written nowadays. I do the latter here because there is no periodical in this town that would print my musings — and quite rightly, because few living souls would wish to read them. Let me then become frankly biographic, a thing which may be permitted to the verse-writing mood.

The collection here presented is made up of reprints of five volumes of verse which have appeared at odd times during the last fifteen years. The last poem in the book was written when I was fifteen, the first, a year ago, so that, roughly speaking, this volume represents the work of twenty-five years.

But the writing of verse hardly appears to me to be a matter of work: it is a process, as far as I am concerned, too uncontrollable. From time to time words in verse form have come into my head and I have written them down, quite powerlessly and without much interest, under the stress of certain emotions. And, as for knowing whether one or the other is good, bad or indifferent, I simply cannot begin to trust myself to make a selection. And, as for trusting any friend to make a selection, one cannot bring oneself to do it either. They have — one’s friends — too many mental axes to grind. One will admire certain verses about a place because in that place they were once happy; one will find fault with a certain other paper of verses because it does not seem likely to form a piece of prentice work in a school that he is desirous of founding. I should say that most of the verses here printed are rather derivative, and too much governed by the passing emotions of the moment. But I simply cannot tell; is it not the function of verse to register passing emotions? Besides, one cherishes vague, pathetic hopes of having written masterpieces unaware, as if one’s hackney mare should by accident be got with a winner of the Two Thousand.

With prose, that conscious and workable medium, it is a perfectly different matter. One finds a subject somewhere — in the course of gossip or in the Letters and State Papers of some sovereign deceased, published by the Record Office. Immediately the mind gets to work upon the “form,” blocks out patches of matter, of dialogue, of description. If the subject is to grow into a short short-story, one knows that one will start with a short, sharp, definite sentence, so as to set the pace:

“Mr Lamotte,” one will write, “returned from fishing. His eyes were red; the ends of his collar, pressed open because he had hung down his head in the depths of his reflection....”

Or, if it is to be a long short-story, we shall qualify the sharpness of the opening sentence and damp it down as thus:

“When, on a late afternoon of July, Mr Lamotte walked up from the river with his rod in his hand...” Or again, if the subject seems one for a novel, we begin:

“Mr Lamotte had resided at the White House for sixteen years. The property consisted of

But with verse I just do not know: I do not know anything at all. As far as I am concerned, it just comes. I hear in my head a vague rhythm:

and presently a line will present itself:

“Up here, where the air’s very clear,”

Or else one will come from nowhere at all: “When all the little hills are hid in snow,”

and the rest flows out.

And I confess myself to being as unable to judge the result as I am to influence the production.

And, as I have said, I have no outside “pointers” at all. Whence should I get it? From the public? From the Press? From writers whom I revere? From my publisher?

As for the Press and the Public. My first book of verse was received with extraordinary enthusiasm by the former. The

Times

praised it for a column; the

Daily News

for a column and a half; the

Academy

gave it a page. The Public bought fourteen copies. With the publication of my second volume the publisher failed. The Press devoted to it less space, but stated that I had not belied my earlier promise; the public bought no copies at all. That may have been because the publisher had disappeared. My third volume received nine notices from the Press; I never had any accounts from the publishers, and, since they are quite honest folk, I presume that, had there been any sales, they would have paid me the few shillings that would have been upon their books. I paid for the publication of the fourth volume and purchased one hundred copies for use as Christmas cards. It received five notices in the Press. (There were no advertisements.) My fifth venture I also subsidized and used for a similar festive purpose. ONE provincial newspaper devoted four lines to it; I believe that two people purchased copies.

It will thus be manifest that, from the Press and the Public I have received no sort of pointer at all, except to suppress these faggots of irregular lines — which are all they are to me.

Is that a test? Or is anything any test? I do not know. I know that I would very willingly cut off my right hand to have written the “Wahlfart nach Kevelaar” of Heine, or “Im Moos,” by Annette von Droste. I would give almost anything to have written almost any modern German lyric or some of the ballads of my friend Levin Schucking. These fellows you know. They sit at their high windows in German lodgings; they lean out; it is raining steadily. Opposite them is a shop where herring salad, onions and oranges are sold. A woman with a red petticoat and a black and grey check shawl goes into the shop and buys three onions, four oranges and half a kilo of herring salad. And there is a poem! Hang it all! There is a poem.

But this is England — this is Campden Hill, and we have a literary jargon in which we must write. We

must

write in it or every word will “swear.”

Denn nach Koln am Rheine

Geht die Procession.

“For the procession is going to Cologne on the Rhine.” You could not use the word procession in an English poem. It would not be literary. Yet when those lines are recited in Germany people weep over them. I have seen fat Frankfort bankers — and Jews at that — weeping when the “Wahlfart” was recited in a red plush theatre with gilt cherubs all over the place.

That I think is why I know nothing about and take very little interest in English poetry. As to my own — that here presented I can say this — there is no single poem in the whole number that I have not been heartily advised by one person or another not to republish. Then comes the publisher — a real publisher, though I imagine a mad one, who offers me money — yes, real money — for the right to publish a Collected Edition! A Collected Edition with nothing left out this publisher commands. What then am I to do? Suppress all or publish all?

To suppress all would be too painful. I have worked at these things; some people will be pleased to read some of them; others will be flattered. They represent emotions, fears, aspirations! And, for the life of me, I cannot tell which, if any, is good and which is the merest trifling.

II

With regard to more speculative matters. I may really say that for a quarter of a century I have kept before me one unflinching aim — to register my own times in terms of my own time, and still more to urge those who are better poets and better prose-writers than myself to have the same aim. I suppose I have been pretty well ignored; I find no signs of my being taken seriously. It is certain that my conviction would gain immensely as soon as another soul could be found to share it. But for a man mad about writing this is a solitary world, and writing — you cannot write about writing without using foreign words — is a

métier de chien.

It is something a matter of diction. In France, upon the whole, a poet — and even a quite literary poet — can write in a language that, roughly speaking, any hatter can use. In Germany, the poet writes exactly as he speaks. And these facts do so much towards influencing the poet’s mind. If we cannot use the word “procession” we are apt to be precluded from thinking about processions. Now processions (to use no other example) are very interesting and suggestive things, and things that are very much part of the gnat-dance that modern life is. Because, if a people has sufficient interest in public matters to join in huge processions it has reached a certain stage of folk-consciousness. If it will not or cannot do these things it is in yet other stages. Heine’s “Procession” was, for instance, not what we should call a procession at all. With us there are definite types — there is the King’s Procession at Ascot. There are processions in support of Women’s Suffrage and against it; those in support of Welsh Disestablishment or against it. But the procession at Koln was a pilgrimage.

Organized state functions, popular expressions of desire are one symptom; pilgrimages another. But the poet who ignores them all three is to my thinking lost, since in one way or another they embrace the whole of humanity and are mysterious, hazy and tangible. A poet of a sardonic turn of mind will find sport in describing how, in a low pot-house, an emissary of a skilful Government will bribe thirty ruffians at five shillings a head to break up and so discredit a procession in favour of votes for women; yet another poet may describe how a lady in an omnibus, with a certain turn for rhetoric, will persuade the greater number of the other passengers to promise to join the procession for the saving of a church; another will become emotionalized at the sight of the Sword of Mercy borne by a peer after the Cap of Maintenance borne by yet another. And believe me, to be perfectly sincere, when I say that a poetry whose day cannot find poets for all these things is a poetry that is lacking in some of its members.

So, at least, I see it. Modern life is so extraordinary, so hazy, so tenuous with, still, such definite and concrete spots in it that I am for ever on the look out for some poet who shall render it with all its values. I do not think that there was ever, as the saying is, such a chance for a poet; I am breathless, I am agitated at the thought of having it to begin upon. And yet I am aware that I can do nothing, since with me the writing of verse is not a conscious Art. It is the expression of an emotion, and I can so often not put my emotions into any verse.

- I should say, to put a personal confession on record, that the very strongest emotion — at any rate of this class — that I have ever had was when I first went to the Shepherd’s Bush Exhibition and came out on a great square of white buildings all outlined with lights. There was such a lot of light — and I think that what I hope for in Heaven is an infinite clear radiance of pure light! There were crowds and crowds of people — or no, there was, spread out beneath the lights, an infinite moving mass of black, with white faces turned up to the light, moving slowly, quickly, not moving at all, being obscured, reappearing.

I know that the immediate reflection will come to almost any reader that this is nonsense or an affectation. “How,” he will say, “is any emotion to be roused by the mere first night of a Shepherd’s Bush exhibition? Poetry is written about love, about country lanes, about the singing of birds.” I think it is not — not nowadays. We are too far from these things. What we are in, that which is all around us, is the Crowd — the Crowd blindly looking for joy or for that most pathetic of all things, the good time? I think that that is why I felt so profound an emotion on that occasion. It must have been the feeling — not the thought — of all these good, kind, nice people, this immense Crowd suddenly let loose upon a sort of Tom Tiddler’s ground to pick up the glittering splinters of glass that are Romance, hesitant but certain of vistas of adventure, if no more than the adventures of their own souls — like cattle in a herd suddenly let into a very rich field and hesitant before the enamel of daisies, the long herbage, the rushes fringing the stream at the end.