Colin Woodard (4 page)

Authors: American Nations: A History of the Eleven Rival Regional Cultures of North America

Tags: #American Government, #General, #United States, #State, #Political Science, #History

Cultural geographers came to similar conclusions decades ago. Wilbur Zelinsky of Pennsylvania State University formulated the key theory in 1973, which he called the Doctrine of First Effective Settlement. “Whenever an empty territory undergoes settlement, or an earlier population is dislodged by invaders, the specific characteristics of the first group able to effect a viable, self-perpetuating society are of crucial significance for the later social and cultural geography of the area, no matter how tiny the initial band of settlers may have been,” Zelinsky wrote. “Thus, in terms of lasting impact, the activities of a few hundred, or even a few score, initial colonizers can mean much more for the cultural geography of a place than the contributions of tens of thousands of new immigrants a few generations later.” The colonial Atlantic seaboard, he noted, was a prime example. The Dutch may be all but extinct in the lower Hudson Valleyâand landed aristocracy may have lost control of the Chesapeake countryâbut their influence carries on all the same.

8

8

Our continent's famed mobilityâand the transportation and communications technology that foster itâhas been reinforcing, not dissolving, the differences between the nations. As journalist Bill Bishop and sociologist Robert Cushing demonstrated in

The Big Sort

(2008), since 1976 Americans have been relocating to communities where people share their values and worldview. As a result, the proportion of voters living in counties that give landslide support to one party or another (defined as more than a 20 percent margin of victory) increased from 26.8 percent in 1976 to 48.3 percent in 2004. The flows of people are significant, with a net 13 million people moving from Democratic to Republican landslide counties between 1990 and 2006 alone. Immigrants, by contrast, avoided the deep red counties, with only 5 percent living in them in 2004, compared with 21 percent in deep blue counties. What Bishop and Cushing didn't realize is that virtually every one of their Democratic landslide counties is located in either Yankeedom, the Left Coast, or El Norte, while the Republican ones dominate Greater Appalachia and Tidewater and virtually monopolize the Far West and Deep South. (The only exceptions to this pattern are the African American majority counties of the Deep South and Tidewater, which are overwhelmingly Democratic.) As Americans sort themselves into like-minded communities, they're also sorting themselves into like-minded nations.

9

The Big Sort

(2008), since 1976 Americans have been relocating to communities where people share their values and worldview. As a result, the proportion of voters living in counties that give landslide support to one party or another (defined as more than a 20 percent margin of victory) increased from 26.8 percent in 1976 to 48.3 percent in 2004. The flows of people are significant, with a net 13 million people moving from Democratic to Republican landslide counties between 1990 and 2006 alone. Immigrants, by contrast, avoided the deep red counties, with only 5 percent living in them in 2004, compared with 21 percent in deep blue counties. What Bishop and Cushing didn't realize is that virtually every one of their Democratic landslide counties is located in either Yankeedom, the Left Coast, or El Norte, while the Republican ones dominate Greater Appalachia and Tidewater and virtually monopolize the Far West and Deep South. (The only exceptions to this pattern are the African American majority counties of the Deep South and Tidewater, which are overwhelmingly Democratic.) As Americans sort themselves into like-minded communities, they're also sorting themselves into like-minded nations.

9

Of course, examining this book's national maps, readers might take issue with a particular county or city belonging to one nation or another. Cultural boundaries aren't usually as clear-cut as political ones, after all, and a particular region can be under the influence of two or more cultures simultaneously. Examples abound: Alsace-Lorraine on the Franco-German border; Istanbul, straddling the borders of Orthodox Byzantium and Turkic Islam; Fairfield County, Connecticut, torn between the discordant gravitational fields of New England and the Big Apple. Cultural geographers recognize this factor as well and map cultural influences by zones: a

core

or nucleus from which its power springs, a

domain

of lesser intensity, and a wider

sphere

of mild but noticeable influence. All of these zones can shift over time and, indeed, there are plenty of examples of cultures losing dominance over even their core and effectively ceasing to exist as a nation, like the Byzantines or the Cherokee. The map immediately preceding this Introduction has boundaries based on the core and domain of each nation circa 2010. If we added each nation's sphere, there would be a great deal of overlap, with multiple nations projecting influence over southern Louisiana, central Texas, western Québec, or greater Baltimore. These boundaries are not set in stone: they've shifted before and they'll undoubtedly shift again as each nation's influence waxes and wanes. Culture is always on the move.

10

core

or nucleus from which its power springs, a

domain

of lesser intensity, and a wider

sphere

of mild but noticeable influence. All of these zones can shift over time and, indeed, there are plenty of examples of cultures losing dominance over even their core and effectively ceasing to exist as a nation, like the Byzantines or the Cherokee. The map immediately preceding this Introduction has boundaries based on the core and domain of each nation circa 2010. If we added each nation's sphere, there would be a great deal of overlap, with multiple nations projecting influence over southern Louisiana, central Texas, western Québec, or greater Baltimore. These boundaries are not set in stone: they've shifted before and they'll undoubtedly shift again as each nation's influence waxes and wanes. Culture is always on the move.

10

Delve deeply into almost any particular locality and you'll likely find plenty of minority enclaves or even micronations embedded within the major ones I've outlined here. One could argue that the Mormons have created a separate nation in the heart of the Far West, or that Milwaukee is a Midlander city stranded in the midst of the Yankee Midwest. You might argue for the Kentucky Bluegrass Country being a Tidewater enclave embedded in Greater Appalachia, or that the Navajo have developed a nation-state in the Far West. There's a distinct Highland Scots culture on Nova Scotia's Cape Breton Island and on North Carolina's Cape Fear peninsula. One could write an entire book about the acute cultural and historical differences between “Yankee core” Maine and Massachusettsâindeed, this is a subject I treated in

The Lobster Coast

(2004). Digging into regional cultures can be like peeling an onion. I've stopped where I have because I believe the values, attitudes, and political preferences of my eleven nations truly dominate the territories they've been assigned, trumping the implications of finer-grain analysis.

The Lobster Coast

(2004). Digging into regional cultures can be like peeling an onion. I've stopped where I have because I believe the values, attitudes, and political preferences of my eleven nations truly dominate the territories they've been assigned, trumping the implications of finer-grain analysis.

I've also intentionally chosen not to discuss several other nations that influence the continent but whose core territories lie outside what is now the United States and Canada. Cuban-dominated South Florida is the financial and transportation hub of the Spanish-speaking Caribbean. Hawaii is part of the greater Polynesian cultural nation and was once a nation-state of its own. Central Mexico and Central America are, of course, part of the North American continent and include perhaps a halfdozen distinct nationsâHispano-Aztec, Greater Mayan, Anglo-Creole, and so on. There are even scholars who make persuasive arguments that African American culture constitutes the periphery of a larger Creole nation with its core in Haiti and a domain extending over much of the Caribbean basin and on to Brazil. These regional cultures are certainly worthy of exploration, but as a practical matter, a line needed to be drawn somewhere. Washington, D.C., is also an anomaly: a gigantic political arena for the staging of intranational blood-sport competitions, where one team prefers to park their cars in the Tidewater suburbs, the other in the Midland ones.

Finally, I'd like to underscore the fact that becoming a member of a nation usually has nothing to do with genetics and everything to do with culture.

a

One doesn't

inherit

a national identity the way one gets hair, skin, or eye color; one

acquires

it in childhood or, with great effort, through voluntary assimilation later in life. Even the “blood” nations of Europe support this assertion. A member of the (very nationalistic) Hungarian nation might be descended from Austrian Germans, Russian Jews, Serbs, Croats, Slovaks, or any combination thereof, but if he speaks Hungarian and embraces Hungarian-ness, he's regarded as being just as Hungarian as any “pure-blooded” Magyar descendant of King Ãrpád. In a similar vein, nobody would deny French president Nicolas Sarkozy's Frenchness, even though his father was a Hungarian noble and his maternal grandfather a Greek-born Sephardic Jew.

b

The same is true of the North American nations: if you talk like a Midlander, act like a Midlander, and think like a Midlander, you're probably a Midlander, regardless of whether your parents or grandparents came from the Deep South, Italy, or Eritrea.

11

a

One doesn't

inherit

a national identity the way one gets hair, skin, or eye color; one

acquires

it in childhood or, with great effort, through voluntary assimilation later in life. Even the “blood” nations of Europe support this assertion. A member of the (very nationalistic) Hungarian nation might be descended from Austrian Germans, Russian Jews, Serbs, Croats, Slovaks, or any combination thereof, but if he speaks Hungarian and embraces Hungarian-ness, he's regarded as being just as Hungarian as any “pure-blooded” Magyar descendant of King Ãrpád. In a similar vein, nobody would deny French president Nicolas Sarkozy's Frenchness, even though his father was a Hungarian noble and his maternal grandfather a Greek-born Sephardic Jew.

b

The same is true of the North American nations: if you talk like a Midlander, act like a Midlander, and think like a Midlander, you're probably a Midlander, regardless of whether your parents or grandparents came from the Deep South, Italy, or Eritrea.

11

The remainder of the book is divided into four parts organized more or less chronologically. The first covers the critical colonial period, with chapters on the creation and founding characteristics of the first eight Euro-American nations. The second exposes how intranational struggles shaped the American Revolution, the federal Constitution, and critical events in the Early Republic. The third shows how the nations expanded their influence across mutually exclusive sections of the continent, and how the related intranational struggle to control and define the federal government triggered the Civil War. The final part covers events of the late nineteenth, twentieth, and early twenty-first centuries, including the formation of the “new” nations and the intensification of intranational differences over immigration and the “American” identity, religion and social reform, foreign policy and war, and, of course, continental politics. The epilogue offers some thoughts on the road ahead.

Let the journey begin.

PART ONE

ORIGINS

1590 to 1769

1590 to 1769

CHAPTER 1

Founding El Norte

A

mericans have been taught to think of the European settlement of the continent as having progressed from east to west, expanding from the English beachheads of Massachusetts and Virginia to the shores of the Pacific. Six generations of hearty frontiersmen pushed their Anglo-Saxon bloodlines into the wilderness, wrestling nature and her savage children into submission to achieve their destiny as God's chosen people: a unified republic stretching from sea to sea inhabited by a virtuous, freedom-loving people. Or so our nineteenth-century Yankee historians would have us believe.

mericans have been taught to think of the European settlement of the continent as having progressed from east to west, expanding from the English beachheads of Massachusetts and Virginia to the shores of the Pacific. Six generations of hearty frontiersmen pushed their Anglo-Saxon bloodlines into the wilderness, wrestling nature and her savage children into submission to achieve their destiny as God's chosen people: a unified republic stretching from sea to sea inhabited by a virtuous, freedom-loving people. Or so our nineteenth-century Yankee historians would have us believe.

The truth of the matter is that European culture first arrived from the south, borne by the soldiers and missionaries of Spain's expanding New World empire.

The Americas, from a European's point of view, had been discovered by a Spanish expedition in 1492, and by the time the first Englishmen stepped off the boat at Jamestown a little over a century later, Spanish explorers had already trekked through the plains of Kansas, beheld the Great Smoky Mountains of Tennessee, and stood at the rim of the Grand Canyon. They had mapped the coast of Oregon and the Canadian Maritimesânot to mention Latin America and the Caribbeanâand given names to everything from the Bay of Fundy (

Bahia Profunda

) to the Tierra del Fuego. In the early 1500s Spaniards had established short-lived colonies on the shores of Georgia and Virginia. In 1565, they founded St. Augustine, Florida, now the oldest European city in the United States.

c

By the end of the sixteenth century, Spaniards had been living in the deserts of Sonora and Chihuahua for decades, and their colony of New Mexico was marking its fifth birthday.

Bahia Profunda

) to the Tierra del Fuego. In the early 1500s Spaniards had established short-lived colonies on the shores of Georgia and Virginia. In 1565, they founded St. Augustine, Florida, now the oldest European city in the United States.

c

By the end of the sixteenth century, Spaniards had been living in the deserts of Sonora and Chihuahua for decades, and their colony of New Mexico was marking its fifth birthday.

Indeed, the oldest European subculture in the United States isn't to be found on the Atlantic shores of Cape Cod or the Lower Chesapeake, but in the arid hills of northern New Mexico and southern Colorado. Spanish Americans have been living in this part of El Norte since 1595 and remain fiercely protective of their heritage, taking umbrage at being lumped in with Mexican Americans, who appeared in the region only in the nineteenth and twentieth centuries. Their leaders have a passion for genealogy that rivals that of the

Mayflower

descendants, and share the same sense of bearing a torch of culture that must be passed down from generation to generation. In 1610 they built Santa Fe's Palace of the Governors, now the oldest public building in the United States. They retained the traditions, technology, and religious pageantry of seventeenth-century Spain straight into the twentieth century, working fields with wooden plows, hauling wool in crude medieval carts, and carrying on the medieval Spanish practice of

literally

crucifying one of their own for Lent. Today, modern technology has arrivedâand the crucifixions are done with rope, rather than nailsâbut the imprint of old Spain survives.

1

Mayflower

descendants, and share the same sense of bearing a torch of culture that must be passed down from generation to generation. In 1610 they built Santa Fe's Palace of the Governors, now the oldest public building in the United States. They retained the traditions, technology, and religious pageantry of seventeenth-century Spain straight into the twentieth century, working fields with wooden plows, hauling wool in crude medieval carts, and carrying on the medieval Spanish practice of

literally

crucifying one of their own for Lent. Today, modern technology has arrivedâand the crucifixions are done with rope, rather than nailsâbut the imprint of old Spain survives.

1

Spain had the head start on its sixteenth-century rivals because it was then the world's superpower, so rich and powerful that the English looked upon it as a mortal threat to Protestants everywhere. Indeed, Pope Alexander VI considered Spain “the most Catholic” of Europe's many monarchies and in 1493 granted it ownership of almost the entire Western Hemisphere, even though the American mainland had yet to be discovered. It was a gift of staggering size: 16 million square milesâan area eighty times greater than Spain itself, spread across two continents and populated by perhaps 100 million people, some of whom had already built complex empires. Spain, with a population of less than seven million, had received the largest bequest in human history, with just one requirement attached: Pope Alexander ordered it to convert all the hemisphere's inhabitants to Catholicism and “train them in good morals.” This overarching mission would inform Spanish policy in the New World, profoundly influencing the political and social institutions of the southern two-thirds of the Americas, including El Norte. It would also plunge Europe into perhaps the most apocalyptic of its many wars and, in the Americas, trigger what demographers now believe was the largest destruction of human lives in history.

2

2

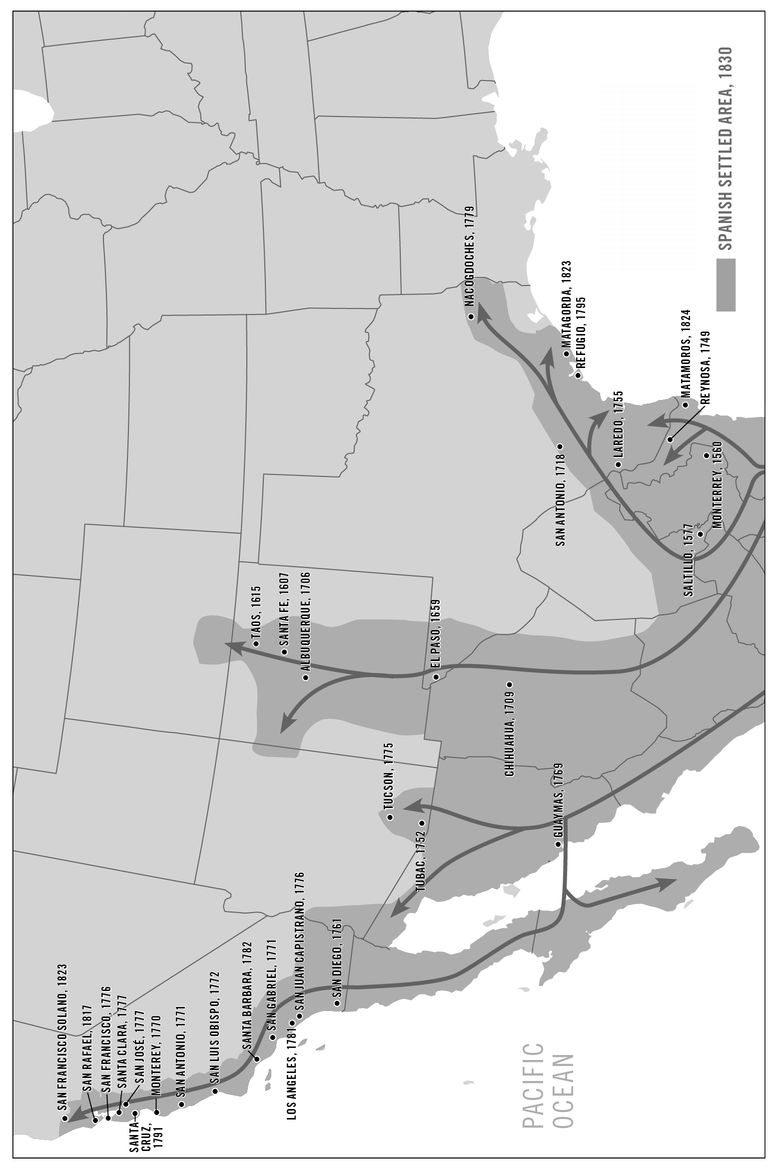

EL NOTRE 1560-1830

Â

History has tended to portray the native peoples of the Americas as mere extras or scenery in a Western drama dominated by actors of European and African descent. Because this book is primarily concerned with the ethnocultural nations that have come to dominate North America, it will reluctantly adopt that paradigm. But there are a few factors to bear in mind at the outset about the New World's indigenous cultures. Before contact, many had a standard of living far higher than that of their European counterparts; they tended to be healthier, better fed, and more secure, with better sanitation, health care, and nutrition. Their civilizations were complex: most practiced agriculture, virtually all were plugged into a continent-spanning trade network, and some built sophisticated urban centers. The Pueblo people the Spanish encountered in New Mexico weren't Stone Age hunter-gatherers; they lived in five-story adobe housing blocks with basements and balconies surrounding spacious market plazas. The Aztecs' capital in Central Mexico, Tenochtitlan, was one of the largest in the world, with a population of 200,000, a public water supply fed by stone aqueducts, and palaces and temples that dwarfed anything in Spain. The Americas were then home to more than a fifth of the world's people. Central Mexico, with 25 million inhabitants, had the highest population density on Earth at the time.

3

3

Other books

Hearts of Gold by Janet Woods

Rory's Proposal by Lynda Renham

The Key To Micah's Heart (Hell Yeah!) by Sable Hunter, Ryan O'Leary

Illusions by Richard Bach

Boardwalk Gangster by Tim Newark

The Wilderness by Samantha Harvey

Crooked Hearts by Patricia Gaffney

Truth Like the Sun by Jim Lynch

Mickey Slips (Tyler Cunningham Shorts) by Sheffield, Jamie

No Defense by Rangeley Wallace