Civilization: The West and the Rest (17 page)

the true wisdom of sovereigns is to do good and to be the most accomplished at it in their states … it is not enough for them to perform brilliant actions and satisfy their ambition and glory, but … they must

prefer the happiness of the human race … Great princes have always forgotten themselves for the common good … A sovereign pushed into war by his fiery ambition should be made to see all of the ghastly consequences for his subjects – the taxes which crush the people of a country, the levies which carry away its youth, the contagious diseases of which so many soldiers die miserably, the murderous sieges, the even more cruel battles, the maimed deprived of their sole means of subsistence, and the orphans from whom the enemy has wrested their very flesh and blood … They sacrifice to their impetuous passions the well being of an infinity of men whom they are duty bound to protect … The sovereigns who regard their people as their slaves risk their lives without pity and see them die without regret, but the princes who consider men as their equals and in certain regards as their masters [

comme leurs egaux et à quelques egards … comme leurs maitres

], are economists with their blood and misers with their lives.

70

Frederick’s musical compositions, too, had real merit – notably the serene Flute Sonata in C major, which is no mere pastiche of Johann Sebastian Bach. His other political writings were far from the work of a dilettante. Yet there was an important difference between the Enlightenment as he conceived it and the earlier Scientific Revolution. The Royal Society had been the hub of a remarkably open intellectual network. By contrast, the Prussian Academy was intended to be a top-down hierarchy, modelled on the absolutist monarchy itself. ‘Just as it would have been impossible for Newton to delineate his system of attraction if he had collaborated with Leibniz or Descartes,’ noted Frederick in his

Political Testament

(1752), ‘so it is impossible for a political system to be made and sustained if it does not emerge from a single head.’

71

There was only so much of this kind of thing that the free spirit Voltaire could stand. When Maupertuis abused his position of quasi-royal authority to exalt his own principle of least action, Voltaire wrote the cruelly satirical

Diatribe du Docteur Akakia, médecin du Pape

. This was precisely the kind of insubordinate behaviour Frederick could not stand. He ordered copies of the

Diatribe

to be destroyed and made it clear that Voltaire was no longer a welcome guest in Berlin.

72

Others were more inclined to submit. An astronomer before he became a philosopher, Kant had first come to public attention in 1754

when he won a Prussian Academy prize for his work on the effect of surface friction in slowing the earth’s rotation. The philosopher showed his gratitude in a remarkable passage in his seminal essay, ‘What is Enlightenment?’, which called on all men to ‘Dare to reason!’ (

Sapere aude!

), but not to disobey their royal master:

Only one who is himself enlightened … and has a numerous and well-disciplined army to assure public peace, can say: ‘Argue as much as you will, and about what you will, only obey!’ A republic could not dare say such a thing … A greater degree of civil freedom appears advantageous to the freedom of mind of the people, and yet it places inescapable limitations upon it. A lower degree of civil freedom, on the contrary, provides the mind with room for each man to extend himself to his full capacity.

73

Prussia’s Enlightenment, in short, was about free thought, not free action. Moreover, this free thought was primarily designed to enhance the power of the state. Just as immigrants contributed to Prussia’s economy, which allowed more tax to be raised, which allowed a bigger army to be maintained, which allowed more territory to be conquered, so too could academic research make a strategic contribution. For the new knowledge could do more than illuminate the natural world, demystifying the movements of heavenly bodies. It also had the potential to determine the rise and fall of earthly powers.

Today, Potsdam is just another dowdy suburb of Berlin, dusty in summer, dreary in winter, its skyline marred by ugly apartment blocks that bear the hallmarks of East German ‘real existing socialism’. In Frederick the Great’s time, however, most of the inhabitants of Potsdam were soldiers and almost all the buildings in Potsdam had some sort of military connection or purpose. Today’s film museum was originally built as an orangery but then turned into cavalry stables. Take a walk through the centre of town and you pass the Military Orphanage, the Parade Ground and the former Riding School. At the junction of Lindenstrasse and Charlottenstrasse, bristling with military ornamentation, is the former Guardhouse. Even the houses were built with an extra storey on top as lodgings for soldiers.

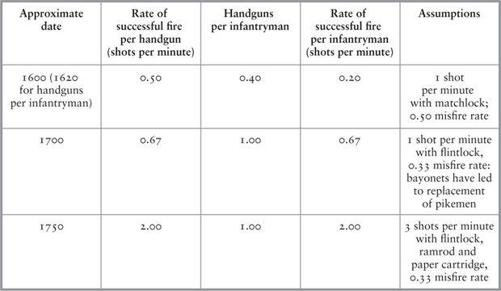

Military Labour Productivity in the French Army:

Rate of Successful Fire per Infantryman, 1600–1750

Potsdam was Prussia in caricature as well as in miniature.

Frederick’s adjutant Georg Heinrich von Berenhorst once observed, only half in jest: ‘The Prussian monarchy is not a country which has an army, but an army which has a country in which – as it were – it is just stationed.’

74

The army ceased to be merely an instrument of dynastic power; it became an integral part of Prussian society. Landowners were expected to serve as army officers and able-bodied peasants took the places of foreign mercenaries in the ranks. Prussia was the army – and the army was Prussia. By the end of Frederick’s reign over 3 per cent of the Prussian population were under arms, more than double the proportion in France and Austria.

A focus on drill and discipline was widely regarded as the key to Prussian military success. In this respect Frederick was the true successor to Maurice of Nassau and the Swedish King Gustavus Adolphus, the masters of seventeenth-century warfare. The blue-clad Prussian infantry marched like clockwork soldiers at ninety paces a minute, slowing to seventy as they neared the enemy.

75

The Battle of Leuthen was fought in December 1757, when the very existence of Prussia was threatened by an alliance of three great powers: France, Austria and

Russia. True to form, the Prussian infantry surprised the long Austrian line, attacking on its southern flank and rolling it up. But then, as the Austrians tried to regroup, they encountered something far more lethal even than a swiftly marching foe: artillery. For deadly accurate firepower was as crucial to Prussia’s rise as the legendary ‘cadaver-like obedience’ of the infantry.

76

In his early years, Frederick had dismissed artillery as a ‘pit of expense’.

77

But he came to appreciate its value. ‘We are now fighting against something more than men,’ he argued. ‘We must get it into our heads that the kind of war we shall be waging from now on will be a question of artillery duels …’

78

At Leuthen the Prussians had sixty-three field guns and eight howitzers as well as ten 12-pound guns known as

Brummer

– ‘growlers’ – because of their ominous rumbling report. The mobile horse-artillery batteries Frederick created soon became a European standard.

79

Their rapid and concentrated deployment on an unprecedented scale would be the key to Napoleon Bonaparte’s later victories.

Weapons like these exemplified the application of scientific knowledge to the realm of military power. It was a process of competition, innovation and advance that quickly opened a yawning gap between the West and the Rest. Yet its heroes remain largely unsung.

Benjamin Robins was born with nothing but brains. Without the means to attend university, he taught himself mathematics and earned his crust as a private tutor. Already elected a member of the Royal Society at the age of twenty-one, he was employed as an artillery officer and military engineer by the East India Company. In the early 1740s Robins applied Newtonian physics to the problem of artillery, using differential equations to provide the first true description of the impact of air resistance on the trajectories of high-speed projectiles (a problem that Galileo had not been able to solve). In

New Principles of Gunnery

, published in England in 1742, Robins used a combination of his own careful observations, Boyle’s Law and the thirty-ninth proposition of book I of Newton’s

Principia

(which analyses the movement of a body under the influence of centripetal forces) to calculate the velocity of a projectile as it left the muzzle of a gun. Then, using his own ballistics

pendulum, he demonstrated the effect of air resistance, which could be as much as 120 times the weight of the projectile itself, completely distorting the parabolic trajectory proposed by Galileo. Robins was also the first scientist to show how the rotation of a flying musket ball caused it to veer off the intended line of fire. His paper ‘Of the Nature and Advantage of a Rifled Barrel Piece’, which he read before the Royal Society in 1747 – the year he was awarded the Society’s Copley Medal – recommended that bullets should be egg-shaped and gun barrels rifled. The paper’s conclusion showed how well Robins appreciated the strategic as well as the scientific importance of his work:

whatever state shall thoroughly comprehend the nature and advantages of rifled barrel pieces, and, having facilitated and completed their construction, shall introduce into their armies their general use with a dexterity in the management of them; they will by this means acquire a superiority, which will almost equal any thing, that has been done at any time by the particular excellence of any one kind of arms.

80

For the more accurate and effective artillery became, the less valuable were sophisticated fortifications; the less lethal were even the best-drilled regular infantry regiments.

It took Frederick the Great just three years to commission a German translation of Robins’s

New Principles of Gunnery

. The translator Leonard Euler, himself a superb mathematician, improved on the original by adding a comprehensive appendix of tables determining the velocity, range, maximum altitude and flight time for a projectile fired at a given muzzle velocity and elevation angle.

81

A French translation followed in 1751. There were of course other military innovators at this time – notably Austria’s Prince Joseph Wenzel von Liechtenstein and France’s General Gribeauval – but to Robins belongs the credit for the eighteenth-century ballistics revolution. The killer application of science had given the West a truly lethal weapon: accurate artillery. It was rather a surprising achievement for a man born, as Robins was, a Quaker.

The Robinsian revolution in ballistics was something from which the Ottomans were of course excluded, just as they had missed out on the more general Newtonian laws of motion. In the sixteenth century Ottoman arms from the Imperial State Cannon Foundry were more than a match for European artillery.

82

In the seventeenth, that began

to change. As early as 1664, Raimondo Montecuccoli, the Habsburg master strategist who routed the Ottoman army at St Gotthard, observed: ‘This enormous artillery [of the Turks] produces great damage when it hits, but it is awkward to move and it requires too much time to reload and sight … Our artillery is more handy to move and more efficient and here resides our advantage over the cannon of the Turks.’

83

For the next two centuries that gap only widened as the Western powers honed their knowledge and weaponry at institutions like the Woolwich Academy of Engineering and Artillery, founded in 1741. When Sir John Duckworth’s squadron forced the Dardanelles in 1807, the Turks were still employing ancient cannon that hurled huge stone balls in the general direction of the attacking ships.

Montesquieu’s epistolary novel

Persian Letters

imagines two Muslims embarking on a voyage of discovery to France via Turkey. ‘I have marked with astonishment the weakness of the empire of the Osmanli,’ writes Usbek on his journey westwards. ‘These barbarians have abandoned all the arts, even that of war. While the nations of Europe become more refined every day, these people remain in a state of primitive ignorance; and rarely think of employing new inventions in war, until they have been used against them a thousand times.’

84