Chatham Dockyard (21 page)

Authors: Philip MacDougall

Chatham Reach. If John Rennie’s plans had come to fruition, this area of the Medway would have been locked into the dockyard with a new cut for shipping created on the far side of the Frindsbury Peninsula.

The remaining trade masters were all abolished seven years later, replaced by foremen.

The years 1832–34 witnessed a further series of reforms that tackled the central weakness of dockyard management, the limited authority of the Commissioner. Under a Parliamentary Act of 1832 Superintendents replaced them, with the Act suggesting that these new officers would perform the same duties as the Commissioners they were replacing. But this was not to be. The subsequent general instructions, empowered by an order-in-council of 18 July 1833, made it clear that the Superintendent had full authority over all yard officers. Furthermore, all correspondence ceased just passing through his office; instead it was directly addressed to him with any returning correspondence, whether from the officers or workmen, having to be approved by him. The introduction of the new title also meant that those styled Commissioner would now cease to hold office, so that the Whig administration was able to make its own appointments. At Chatham, the newly appointed Superintendent was Sir James Alexander Gordon, the warrant for this appointment being dated 9 June:

By the Commissioners for executing the office of Lord High Admiral of Great Britain and Ireland to Sir James Alexander Gordon, KCB, a Captain in His Majesty’s Navy, hereby appointed Captain Superintendent of His Majesty’s Dock Yards at Chatham and Sheerness by virtue of the power and authority to us given we do hereby constitute and appoint you Captain Superintendent of His Majesty’s dockyards at Chatham and Sheerness to be employed in conducting the business of the said dockyards during our pleasure willing and requiring you to take upon you the charge and duties of Captain Superintendent of the said dockyards accordingly and to obey all such instructions as you may from time to time receive from us for your guidance in the execution of the said duties strictly charging and commanding all persons employed as subordinates to you to behave themselves jointly and severally with all respect and obedience unto you as their Captain Superintendent and for your care and trouble in the execution of the duties of your office you will be entitled to receive a salary of £1,000 per annum until further orders and for so doing, this shall be your warrant.

13

Totally omitted from the Act, and resulting from an 1831 policy document, was the recommendation that appointed Superintendents should retain their naval rank. Like the former Commissioners, they were to be drawn from serving naval officers, but unlike Commissioners they were not to lose their seniority. For this, there were sound reasons. Those who had been appointed to the post of Commissioner, and so without naval rank, had frequently found their authority undermined when working with those of naval rank, the latter sometimes countermanding their instructions.

With regard to the reforms of 1833–34, a backward step concerned the reading of instructions to the officers. Prior to 1833, the principal officers of the yard had collected together, listened to the Commissioner reading the instructions from London and had then jointly discussed how these duties might be performed. From July 1833, those meetings were to cease. Instead, the Superintendents were merely to read the orders of the day, the officers being immediately despatched to their duties. Unable to share their problems with each other, they were forced to approach the Superintendent as individuals, communicating with him in private. As was noted by Bromley, a senior clerk of the Admiralty, this situation not only prevented the superior officers from working in concert, but created ‘petty jealousies’. A further retrograde step created by the instructions of 1833 was the ending of the daily meetings that once took place between the superior and inferior officers.

Relations between the Admiralty and Navy Board during the period 1816 to 1832, despite a potential for animosity, was one of relative tranquillity. In part, this was a result of the extraordinary longevity of the Tory administration under Lord Liverpool with Robert Dundas, 2nd Viscount Melville, the longest serving First Lord. Having taken office in February 1812 Melville had, by 1816, not only appointed the Comptroller, Sir Thomas Byam Martin, but the majority of those who made the Navy Board. Through a number of careful selections, Melville created a politically allied body that had every reason to make the system work. Nevertheless, members of the Navy Board were still intent upon upholding their own professional opinion. In particular, differences occurred over the extent to which the dockyards should economise following the conclusion of the war with Napoleon. Melville proposed that the workforce should both receive a wage cut and work longer hours, a view supported by Robert Barlow, the Chatham resident Commissioner from 1808–23. However, Martin, as Barlow’s

senior, was quick to take issue, unhappy that he so freely supported the view of the Admiralty against that of the Navy Board:

Our friend Barlow seems to think that if we have the right to keep the men in the yard ten hours we have an equal right to demand ten hours active hard labour or a scheme of task, when the very Commissioners of Naval Revision admits that the extension of the men working by task shall entitle them to earn half as much again, and in the merchant yards double.

14

In his efforts to maintain artificer numbers within the dockyards the numbers that he considered adequate for the works to be performed, Martin appears to have received the support of a former First Lord, the Earl St Vincent:

I agree with you

in toto

as to the rapid ruin of the British Navy. Instead of discharging valuable and experienced men, of all descriptions from the dockyards, the Commissioners and secretaries of all the boards ought to be reduced to the lowest number they ever stood at and the old system resorted to. One of the projectors of the present diabolical measures should be gibbeted opposite to the Deptford yard and the other opposite the Woolwich yard, on the Isle of Sad Dogs.

15

In general, Martin was highly critical of those who called for excessive economies and supported measures that protected the most skilled workers from dismissal. Nevertheless, during the years that followed upon the ending of the wars against Napoleon, numbers employed at Chatham were dramatically reduced. Whereas in 1814, the total workforce at Chatham had stood at 2,600, the number employed by 1832 was much nearer to 1,300.

The ability of the Admiralty and Navy Boards to work in harmony during the years that followed the Napoleonic Wars did not extend to the Whig-led coalition that entered power in November 1830. Having experienced, while First Lord between February and September 1806, the difficulties that could result from a hostile inferior Board, the new Prime Minister, the 2nd Earl Grey, was intent upon abolishing the Navy Board. Shortly after his accession to office, the new First Lord of the Admiralty, Sir James Graham, with the help of John Barrow, the senior permanent Secretary to the Board of Admiralty, put together a discussion document that outlined the reasons for abolishing the Board while indicating how it was to be replaced. Instead of an inferior Board, a number of principal officers were to be appointed, these to carry out tasks previously performed by the Navy Board. These officers were neither to act in concert nor have any form of executive authority. Instead, a naval lord was to be placed in immediate authority over each of them, with each principle officer having only the power to refer matters to his directing naval lord for discussion by the Board of Admiralty. It was upon the terms of this discussion paper, with but a few amendments, that the Naval Civil Departments Act, which reached the statute books on 9 June 1832, was ultimately based and which was responsible for the complete abolition of the Navy Board.

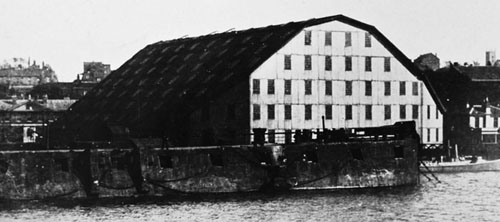

An important addition to the yard during the early nineteenth century was this building, standing at the head of No.4 Dock and which contained the pumping machinery that was eventually to allow Chatham to acquire docks of greater depth. Prior to the arrival of steam pumps, the dry docks had been gravity drained and could not have a depth below that of the low tide level.

A major problem for the newly reformed system was the general expansion of dockyard business and a consequent growth in correspondence directed to the Admiralty. According to Barrow, there was a 33 per cent growth in letters received and despatched from the Admiralty during the period 1827 to 1833. Graham had believed the opposite would take place. In 1836 Barrow went so far as to indicate that the Admiralty was being simply overwhelmed by becoming directly involved with all matters directly relating to dockyard matters.

16

A reference to the Admiralty minute books confirms this: one entry indicates that the principal officers were not to oversee the accounts without these being examined, on a quarterly basis, by members of the Admiralty Board – even though that Board had no understanding of accountancy matters.

17

A further aspect of the Whig-led coalition reforms of this period was a desire to ensure that every member of the workforce worked with the highest possible levels of efficiency. In particular, the Whigs were unhappy with payment by task and job (piece rates), believing that this particular means of remuneration led to work being rushed. Conversely, they also questioned payment at a fixed daily rate, believing that this failed to encourage anything other than work performed at a most leisurely pace. The solution adopted was a complete revamping of the wage system through the introduction of a scheme known as ‘classification’ and by which artisans and labourers were paid according to their perceived merit. Introduced in 1834, it divided the workforce into three classes, with the most efficient placed into the highest, or first class, and paying them at a higher rate than other members of the same trade group who had been placed in either the second or third class. Designed to encourage higher rates of work output, it was supposed to encourage those in the second or third classes to work with a degree of efficiency that would eventually lead to promotion into the class above.

The No.2 Slip at Chatham was the first to be covered, with the roofing added in 1810. Unfortunately, this slip cover no longer exists, having been destroyed by fire in 1966.

In completely overturning the existing system of wage payment, classification was seen by the mass of the workforce as distinctly unfair. Previously, two factors had governed wage rates. First and foremost was the distinction between workers of different skill levels or trades. Within each of the yards a shipwright, the most skilled of all dockyard workers, was guaranteed a higher wage than that of either a caulker or an anchor smith. Similarly, the anchor smith earned more than a rigger or yard labourer. However, the precise wage earned was further determined by whether the worker concerned was paid by the day or had been placed on piece work. To ensure fairness, a book of prices had been maintained and frequently updated, this indicating the monetary reward attached to items of work agreed and completed.

Upon the introduction of classification, the amount of work paid by piece rate was restricted with differentiation by skill distorted. Under the scheme of classification it became possible for a labourer appointed to the first or highest class to receive earnings that paralleled many of those who performed a skilled trade. Similarly, a lesser skilled artisan might find himself in receipt of earnings considerably in excess of a large proportion of shipwrights. However, it was not the partial ending of the pre-existing differential wage structure to which the dockyard workforce was primarily opposed. Instead, it was the divisive nature of the scheme that permitted only a small select group of workers to earn the highest possible wage. While the right to work ‘task’ and ‘job’ had, under the old system, been strictly limited as to numbers, it had at least been operated on a ‘turn and turnabout principle’.

18

In other words, within any given year, most would have participated, with annual earnings more or less equitable between those of the same trade.