Brittle Innings (8 page)

The Titan pulled out the thronelike chair at the end of the table and lowered himself into it. Even sitting, he had a good foot on Musselwhite. A helluvan entrance. Ankers, Heggie, and Dobbs had frozen in place, with tea glasses or forks lifted to their mouths. Me too, I guess.

“Gentlemen, meet Jumbo Hank Clerval,” Musselwhite said. “Glad you could join us, Jumbo.”

“Thank you.” The big guy’s voice was like a ship’s gun booming over deep water.

“Meet the new guys,” Musselwhite said. “Ankers, Dobbs, Heggie, and Bowes. Bowes is their silver-tongued spokesman.”

“Call him Boles,” Parris said. “With an

l

.”

“Delighted to meet yall,” Jumbo said, glancing at us with what seemed like real curiosity. Despite the

yall

, he had a Frenchified accent, an odd lilt that rode the natural booming of his voice. Jumbo—how else could I think of him?—turned to me. “How do yall like Highbridge, Mr. Boles?”

“Boles aint

my

spokesman,” Ankers said. “I am.”

“Actually, Mr. Clerval, Danny

cain’t

talk,” Junior Heggie said, a hiccup in his voice.

Everybody, including Jumbo and me, looked at Junior as if he’d belched at a piano recital. Not that I didn’t welcome his explanation; only that, being so bashful, he’d boggled us all just by speaking. “But I’m shore he can play ball,” he hurried to add.

“He looks like a player,” Jumbo said.

“He looks like a chitlin with ears,” Trapdoor Evans said.

I flushed tomato-red again. The whole table, except for Heggie and Jumbo, guffawed. In Jumbo’s case, I couldn’t tell if he hated jabs at people’s looks or if he had the sense of humor of a cast-iron pot. In my view, Evans hadn’t meant to hurt me; just to get off a funny saying, a josh.

“Too bad about your disability, Mr. Boles,” Jumbo said. “I’m Henry Clerval. Muscles”—he nodded at Lon Musselwhite—“has an imperfect grasp of the etiquette of introductions.”

Mariani whistled, meaning, “Boy, he popped you, Muscles,” but Jumbo frowned at the other guys’ sniggerings.

“You’re a big one to talk about

my

imperfect Emily Posts,” Musselwhite said. “Coming down here with your cap on. You owe the house kitty a dime, Jumbo.”

“A dime!” the ballplayers all cried. “Ante up! Ante up!”

Jumbo’s yellow eyes darted. Bare feet were okay at Kizzy’s table, I guess, but wearing a cap indoors was a McKissic House no-no. Like you’d been raised in a pigsty. Jumbo yanked it off and pressed it down into his lap, out of sight. His hair was greasy black, with a shock of silver-white in the middle of his lumpy forehead and streaks of nickel-gray around his mangled-looking ears. Cripes, I thought, if you staggered into him on a pitch-black street, the fella’d give you about twelve quick heart attacks. Even the overhead lights and the ragging of his fellow Hellbenders couldn’t hide his weirdness. I was ugly, but this guy’d been put together in a meat-packing plant by clumsy blind men.

Everyone called Clerval Jumbo, including Musselwhite, and Musselwhite towered over half the guys on the team. It was scary, those two big palookas sitting there and Jumbo making Musselwhite look like a midget. I wanted to bolt for my room, but I didn’t

have

a room yet. About then, a line job at Deck Glider back in Tenkiller didn’t seem so bad a fate.

Although I didn’t get up and run, I had a devil of a time eating. Not Jumbo. He anted up his dime and dug in, paying no attention to the war talk, baseball gossip, and gripes about wages or family problems going on around him. He asked for, or picked off in the passing, every bowl of vegetables on the table. In fact, he wiped out the mashed potatoes, the field peas, the okra, and the squash. He drank a pitcher of water. He inhaled half a wheel of cornbread and a dozen biscuits. He cut one of Kizzy’s banana cream pies in two and knocked back half of it like it was a jigger of hooch. The last to stumble in, he finished chowing down first, then laid his greasy napkin aside and gazed cowlike and content around him.

“Please excuse me,” he said to Muscles in his bassoon of a voice.

“You’re excused.” Musselwhite gnawed on his second or third pork chop. “If there’s an excuse for you.”

Jumbo said, “Gentlemen,” then unfolded upward from his chair. He ducked out clutching his Hellbenders cap and made his way up the foyer staircase. The stairs creaked under him (but not much more than they would’ve for Junior Heggie or me); and he disappeared, leaving behind a fleet of empty bowls, his own slick china plate, and a table of half-amazed men. Not even the old hands, it hit me, had totally adjusted to either his looks or the shows he put on at mealtimes.

“The Great Thunderfoot,” Reese Curriden said.

“Hell, that’s Sudikoff,” Trapdoor Evans said. “Jumbo’s dainty next to Sudikoff. A regular twinkletoes.”

Sudikoff, a married fella, wasn’t there to defend himself. He was chief backup at first base, though: the graceful lummox who’d tried to fill in for Jumbo at practice.

I can’t recall much else about my first sit-down meal in Highbridge, not even if I got a piece of Kizzy’s banana cream pie, a treat renowned countywide. Jumbo’s performance wiped every later impression of that meal right out of my head.

7

S

oon after, every Hellbender, including married fellas from the Cotton Creek district, along with our driver and unofficial team manager, Darius Satterfield, had crowded into the parlor for Mister JayMac’s big meeting.

The only person not there to begin with was Jumbo Clerval, who, like Buck Hoey had charged that afternoon, seemed to have a weird privileged-character status. Well, why not? “When does a gorilla show up for dinner?” “Whenever he damn well feels like it.”

Anyway, the parlor burst with edgy ballplayers, not counting Jumbo. Sweat ran down my sides. Every face in the room, even with a fan creaking overhead, looked greasily sequin-sprinkled. Chairs, footstools, sofa backs, even the floor—players sat or sprawled on any sort of furniture, or surface, they could find.

In wrinkled seersucker trousers and a sweated-out dress shirt, Mister JayMac had worked his way, along with Darius, to the front of the parlor. Darius set up an easel and a book of flip charts to help Mister JayMac explain the Hellbenders and the CVL to Ankers, Dobbs, Heggie, and me. It meant a tedious rehash for the old hands, but nobody squawked. Not even Buck Hoey, who perched on a sofa back to the rear, an expression on his face like, Hey, what a welcome refresher, we’re all so lucky to get the full scoop again.

“Gentlemen, hayseeds, and hangers-on,” Mister JayMac said when Darius had his flip charts ready. “As most of yall know, we play a seventy-seven-game season. Today, after a month of what passes for some of yall as top-notch baseball, we’re a shabby seven and eight, five games back a the Opelika Orphans, a crew I once wouldn’t have reckoned fit to climb a molehill without succumbing to oxygen deprivation. Muscles called them mewling pansies, and we trail them by five. So what does that make us?”

“Pansy chasers,” Buck Hoey said.

Nobody laughed. Like Jumbo, though, Buck Hoey seemed to have a special status; he could rag the boss—some—without getting sent to his room. Anyway, I felt again how hard it would be to take his job away. And if I did, the other guys would probably resent my success.

Mister JayMac looked around. “Where’s Jumbo? Didn’t he make it back for supper?”

“Like the locust made it to Pharaoh’s Egypt,” Hoey said.

That line

did

get a laugh.

“So where is he now? What the hell’s he doing?”

“Conferring with Count Tallywhacker,” Hoey said. “That’s why it’s taking him, uh, so long.”

A kind of hesitant edgy laugh this time. Mister JayMac curled his lip the way you would if a whiff of spoiled poultry spilled from your Frigidaire. But he sent Euclid upstairs to fetch Jumbo from his third-floor apartment.

“So

looong

,” Hoey said as Euclid went by. This time, half a dozen guys whooped like world-champeen morons.

“Hush,” Mister JayMac said. I realized then, or gradually over the next few days, that Mister JayMac never said, “Shut up.” I’d heard a lot of “Shut ups” in my short life, so I liked the way he said “Hush” instead.

“Any of yall who’ve been dogging it’d better look sharp,” he said. “We’re taking on some young fellas who can

play

. I’ve seen em. This isn’t hearsay, but observed fact.”

“High school wonders,” Buck Hoey said.

“Perhaps,” Mister JayMac said. “But I don’t like being tied for fourth place in this league, and I won’t allow us to stay in fourth if good alternatives to mediocrity present themselves. Maybe they already have.”

Euclid came into the parlor ahead of Jumbo Clerval, who, by the looks of him, had “dressed” for the meeting. He wore a humongous pair of wingtip Florsheims, a pair of patched gray pants, and a shiny black frock coat. Euclid played tug to Jumbo’s ocean liner and, as soon as he got the big man among us, tooted on out of the room. Jumbo’s head, capless now, spiked up almost to the picture molding. He slouched against the wall, straight across the doorway from Buck Hoey on the broken-backed sofa. It looked as if Mister JayMac might say something to him, bawl him out even, but he didn’t. He nodded at us four rookies.

“Yall come up here. I want everybody to see you.”

Ankers, Dobbs, Heggie, and I sidled to the front of the room to stand beside the easel. Ankers may’ve been the only one of us not unsettled by the spotlight. When Mister JayMac introduced us, he stepped out and gave a clasped-hands salute, like a boxer greeting a ringside crowd.

“High school graddyiots,” Hoey said.

“Actually, Mr. Ankers has only completed his sophomore year,” Mister JayMac said.

The Hellbenders stared at Ankers like he was a sideshow freak. Unless he’d been held back a time or two, he was fifteen years old, a baby with the stubble of a lumberjack.

“All right,” Mister JayMac said, “give these fellas a friendly Hellbender hello. Ready? Hip, hip . . .”

“Hooray,” the regulars said, without much in it.

Mister JayMac told them to try again. “Hooray!” they said, with maybe an exclamation point. “Again,” he said. They did a third cheer so loud it more or less mocked the idea of hip-hip-hooraying. But Mister JayMac nodded and tapped a pointer on the first page of his chart:

CHATTAHOOCHEE V ALLEY LEAGUE / CLASS C PROFESSIONALS

“Ever last fella here ought to be reminded how damned lucky yall are to be playing ball,” he said. “You could be training as infantry replacements with all the scared puppies out to Camp Penticuff. Or crawling on your guts toward a bunker full of deadeye Jerries or Japs.”

“We could all be dead,” Hoey said.

“You could indeed!” Mister JayMac roared. “But no, thank God, yall’re privileged to be playing baseball, the national pastime, and getting paid for that hardship to boot.”

“Some of you guys’re getting

paid?

” Hoey said.

“Can it, Hoey,” Lon Musselwhite said.

“Major league baseball continues on presidential sufferance and the affections of our war-weary citizens. Minor league ball is wounded. Nationwide, the farm system is down to ten training leagues in only seventy cities, and, as I know from my work on the draft board, Uncle Sam needs even more able-bodied men to defeat the foes of democracy abroad.

“Listen up now,” Mister JayMac went on. “The Chattahoochee Valley League, one of the youngest around, is a small-town league, with a pitiful ‘C’ training classification, but we make it in spite of the war because we’re the hardest-playing saps anywhere and flat-out beaucoups of fun to watch. Wouldn’t you agree, Mr. Nutter?”

“Yessir.” Creighton Nutter was a married relief pitcher, a balding guy in his late thirties.

“In addition,” Mister JayMac said, “our eight teams are near to one another. The President and the Office of Price Administration appreciate the fact it doesn’t siphon off all that much gas or use up that much tire rubber for one CVL team to travel to another CVL team’s field for a three- or four-game series. Jes last year, the Attorney General said the CVL is the only league he’s ever visited where the National Anthem plays at the end as well as at the start of every contest. A tribute to our national pride. Let me further remind yall that FDR himself views ballplayers as morale boosters and heroes. I concur. At least the good ones are. The bad ones, on the other hand, are—”

“Traitors.” Jumbo’s judgment boomed and echoed.

It stopped Mister JayMac for a second. “Near to,” he said. “Playing the national pastime bad is like spitting on Old Glory. A sorry bungler may not purposely affront the game, but it’s still damnably hard to forgive him.”

“Amen,” Lon Musselwhite said.

Mister JayMac turned to us rookies. “Mr. Boles, tell us the locations and names of the eight teams in the CVL.”

My tongue jumped to the roof of my mouth. My eyes cut around like minnows. The last time I’d been in Mister JayMac’s presence, I’d had at least stammering use of my own tongue.

He remembered that.

“Tell us

one

team in the CVL,” Mister JayMac said. “

Other than

the Hellbenders.”

“Speak up, dummy!” Hoey shouted this out.

Darius, over Mister JayMac’s shoulder, said, “The Boles boy is a dummy, sir. Got no voice.”

Mister JayMac gave me a put-out look, like he’d asked for swordfish steak and the waiter’d brought him a lousy crawdad. Quick, though, his gaze jumped over to Junior Heggie, and he asked Junior to do the naming I couldn’t.

“The Opelika Orphans,” Junior Heggie said.

“Well, sure,” Mister JayMac said. “Name the other six.”

Junior studied his shoes. He came from the other side of the state. It’d’ve been easier for him to name the last six British prime ministers.

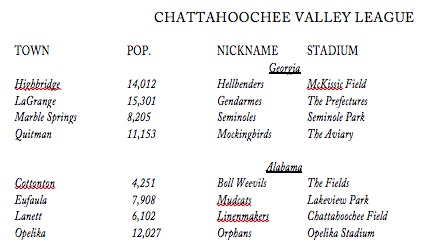

“Darius, the chart,” Mister JayMac said. Darius flipped the top sheet over the back of the easel and showed us a new page. General JayMac, an Allied officer in a secret command post, briefing his staff. “All right. Look here.” He rapped the chart with the top of a collapsible pool cue:

Mister JayMac told us something about each franchise: what big league club it belonged to, its strengths and shortcomings, and why Highbridge, given our talent, should be in first place.

“Gentlemen, it’s a minor disgrace that after fifteen games we’re tied for fourth behind the Orphans, the Gendarmes, and the Mudcats. It’s a

major

disgrace we’re tied with that sorry crew from Cottonton. Cottonton! A hole in the road! They’ve got chickens on Main! I once saw a goat—an

animal

—figure in a call over there!” He banged his pool-cue pointer on the flip chart. It ripped the page listing the CVL’s franchises. “Most of the Weevils are ex-semipros off mill teams. They’re hacks and mercenaries. It’s absurd to be locked in a fourth-place tie with em. Absurd!” The pointer whacked the chart, and all us rookies, except maybe Ankers, flinched.

“Steady down, Mister JayMac,” Darius said.

Mister JayMac steadied. He left off being a high-powered general and became instead a low-key explainer—all Darius’s doing, as maybe only Junior Heggie and I noticed.

“All right. We’ve got ex-major leaguers in this room. I want those men to raise their hands.”

You’d’ve figured that with so many old guys on the team, journeymen players sliding into middle age and past, maybe five or six would’ve had at least a few at bats or some heavy-duty bench time in the bigs. But only two men raised their hands; neither, it did my soul good to see, was Buck Hoey.

“You gentlemen come up here,” Mister JayMac said. He tapped the floor, and two fellas I’d’ve never guessed shuffled to the front of the room. Ex-big leaguers! Even Ankers got excited.

“Huzza!” Hoey called. “Failures! They went up, but they came back down!” Joshing, but not totally. His little barb rang true.

“Failures!” some other guys chanted. “Failures!”

“At least we made it up,” Creighton Nutter said,

“I think you made it

all

up. You and Dunnagin’s adventures in the bigs’re all in your heads.” Laughter. Musselwhite was captain, but Hoey did his bit as official team comedian.

“In the record books, you mean,” Nutter said.

Nutter and Dunnagin, our former Showmen. Nutter reminded me of the chip-on-his-shoulder second barber in a two-man shop, a fella who argues because he’s sick of playing second fiddle. He had acorn-colored skin, which he’d probably got from a north Georgia farmer with Cherokee blood.

Dunnagin was thirty-eight or -nine, a mick with jet-black hair and eyes as blue as core samples of Canadian sky. His upper body said weight lifter; his legs said whooping crane. At practice that morning he’d worn full catcher’s gear: chest pad, shin guards, birdcage, the works. Even then I’d noticed his shin guards were wider than his thighs. You expected him to tumble over, like a tower of alphabet blocks with a block too many at the top.

“Tell them who you played for, Mr. Nutter,” Mister JayMac said, “and what kind of record you compiled.”

“Murder,” Hoey said. “Corrupting female minors.”

Nutter blew off the kibitzing. “In 1927, I pitched in nineteen games for the Boston Braves. Seventy-six innings.”

“Ah, but your

record

,” Hoey said. “Tell us your

record

.”

Nutter glanced over at Mister JayMac, who gave him a nod. “I was four and seven with two saves. My ERA was . . . 5.09.”

Total silence. Hoey may’ve already known Nutter’s record, but most of the other Hellbenders didn’t.

“Four and seven,” said Vito Mariani, himself a pitcher. “Not so hot. That earned run average aint so hot either.”

“Mr. Mariani, you have no ERA in the majors at all,” Mister JayMac said. “And there’s not another pitcher in Highbridge today with more big-league victories than Mr. Nutter nailed down for the Braves. Give him the respect due him.”

Ankers started clapping, the rest of us joined in. Nutter glued his chin to his chest, but smiled an angry-barber smile, like he disagreed with a customer’s opinion of the New Deal but didn’t want to job his tip by saying so aloud.

“Very well, Mr. Dunnagin,” Mister JayMac said, “tell us in what capacity you reached the bigs and how you fared there.”

Dunnagin stood like a Marine at parade rest. “I went up as a puling babe with the St. Louis Browns in 1924. I played reserve catcher and pinch hit for all or parts of the next six seasons.”

“After which the Browns cut you?” Mister JayMac asked.