Black Gotham: A Family History of African Americans in Nineteenth-Century New York City (41 page)

Read Black Gotham: A Family History of African Americans in Nineteenth-Century New York City Online

Authors: Carla L. Peterson

But then the waters get muddied. In his letter, Mann insisted that he was not so much troubled about rank as he was about DeGrasse’s management of the hospital, and that he, Mann, had an obligation to

“take care of medical supplies, especially spirituous liquors and to protect the hospital fund from misuse.” Basically, Mann was accusing DeGrasse, just as Marcy did later, of misappropriating liquor. The officer who supported Mann’s claim agreed that DeGrasse had “abused his privileges” and “committed misdemeanors,” and concluded that charges should be preferred against him.

Interestingly enough, in this episode James Beecher stood up for DeGrasse. He did so, however, not so much because he believed in or cared about the young black surgeon but because he was stung by the accusation of intemperance in his regiment. There was not one instance,” he maintained, “brought to my notice of an intoxicated officer and but one, of an intoxicated man, a thing which can probably be said of no other regiment, certainly in the Dept.” DeGrasse, he concluded, was “dispensing hospital liquor to nurses and stretcher corps when on extra duty” in accordance with governmental regulations. Beecher was so perturbed that he threatened Mann with court-martial.

10

Here’s one way of connecting the two incidents. Henry Marcy joined the regiment as head surgeon in November 1863, right in the middle of the Mann-Beecher charges and countercharges. He might have worried that Beecher would prefer DeGrasse to him, and concluded that persuasive accusations of misappropriation of liquor and drunkenness were charges that might sway Beecher’s opinion. Marcy must have been aware of Beecher’s past. In the late 1850s, while serving as a missionary abroad, Beecher discovered that his wife was an alcoholic. The couple returned home, his wife was institutionalized, and Beecher made officer in a New York regiment where one of his brothers served as chaplain. He fell in love with another woman and was guilt ridden. Fearing that he was going mad and would be court-martialed, the Beecher family obtained an honorable discharge for him and placed him in a sanatorium. After his wife died, Beecher reentered the army as commander of the Thirty-fifth, courted the woman he loved throughout 1864, and married her a year later.

11

Here are the two possibilities I’m left with. A black army surgeon addicted to alcohol and unable to perform his duties. Or an unstable commanding officer with a history of alcoholism in his family and attracted

to a woman not his wife, coupled with a white doctor threatened by a competent black doctor. If the latter, the trial raises larger questions: When would a black man’s authority ever be accepted? When would his word ever be taken over that of a white? When would blacks’ capacity for citizenship ever be acknowledged?

DeGrasse concluded his statement with a defense. “My character as a gentleman and my upright deportment,” he wrote, “have never been questioned by officers or men until these, I think, unfounded charges were preferred.” To this he added a plea: “My honor and my reputation are at stake, not only here in the army, but at home and wherever I am known.” He was found guilty of all charges and cashiered. Details of his life thereafter are murky. He died in Boston in November 1868.

Beecher moved his family to upstate New York. Increasingly “queer” in behavior, he eventually went mad and wandered from one insane asylum to another. In 1886, he ended his life by putting a bullet through his mouth.

12

DeGrasse’s court-martial pitted black man against white, but within the black community tensions flared among black men. Perhaps James McCune Smith alone could have made his former schoolmates realize the folly of internal dissension at a time when unity against the real enemy—white racism—was essential. But he was slowly dying.

For years, Smith had suffered from an enlarged heart and what he called an “overworked nervous system.” In the early 1860s, his health deteriorated rapidly; death came in November 1865. The

Weekly Anglo-African

published an obituary that was long but restrained in tone, as if any expression of sorrow would open an outpouring of uncontrollable grief. It stuck to an enumeration of facts: Smith’s illustrious career at the African Free School; early apprenticeship to a blacksmith; later private education; medical school in Glasgow; position as doctor of the Colored Orphan Asylum; participation in the antislavery movement; affiliation with the Episcopal Church. Only when he reached the moment of death did the writer let himself go:

He will be greatly missed, not alone in the line of his profession, and by his immediate family connection, but as a public man; and his death is as well lamented by them as by his family and relatives. A large circle of friends, with weeping hearts, attended his funeral, among whom were ten clergymen of different denominations, and most of whom followed him to his quiet resting place.

13

Smith had been too ill to attend the National Convention of Colored Citizens held in Syracuse in the fall of 1864. Henry Highland Garnet had called for the convention in order to figure out how best “to promote the freedom, progress, elevation, and perfect enfranchisement, of the entire colored people of the United States.” Among those in attendance were old-timers Frederick Douglass, George Downing, J. W. C. Pennington, and Robert Hamilton, joined by men of the younger generation like Peter Guignon’s brother-in-law, Peter W. Ray. If Garnet expected unity in a time of crisis, he was sadly disappointed. From the beginning, controversy dogged him inside and outside the convention hall. Aired on the convention podium and in newspaper columns, the disagreements were public and acrimonious.

On the city streets, delegates had to contend with the hostility of the good citizens of Syracuse. Douglass reported that he had been confronted by a group of men who demanded to know “Where are the d—d niggers going?” Worse still, a group of Irish rowdies accosted Garnet and threw him to the ground. They took his wooden leg, stole his silver-plated cane, and forced him to crawl through the mud.

14

Horrified delegates took up a collection and raised forty dollars to replace Garnet’s cane.

Amity between Garnet and his co-conventioneers ended there, however. Garnet was unhappy that Douglass had been elected president of the convention even though he, Garnet, had been the one to call for it. Still more humiliating were the suspicions voiced over his involvement with the African Civilization Society. Garnet complained that even “at this late day in his career … there had been a strong disposition to throw him on the shelf, on account of his connection with the African Civilization Society.” George Downing pressed the attacks. He

angrily denounced the African Civilization Society as a “child of prejudice” and Garnet as a race traitor who had remained silent when the society’s members declared that “it would be well if every colored man was out of the country.”

Garnet won the verbal battle. With his sharp sense of wit intact, he wondered who was really lame: “Mr. Downing and I have in days gone by had many hard intellectual battles. He has hurled against me all the force of his vigorous logic, and I struck him back again with all my power. If I smarted from his blows, I think I may say he went away a little lame; and he has never forgotten it.”

15

But he lost the ideological war. Black leaders sensed that victory was at hand and threw all their energy into acquiring the full rights of citizenship in the land of their birth.

Rejected by his own, Garnet was, however, embraced by the nation and savored one final triumph. Early 1865 found him hopeful. He was convinced that the wounds that had torn the nation apart could be healed, North and South, blacks and whites unified. By heeding the painful lessons of the past, the nation could build a brighter future. In February, he was honored as the first black American to address the U.S. House of Representatives. His “Memorial Discourse” memorialized slavery itself. Recognizing that slavery was a universal system, Garnet placed his speech within a long tradition of antislavery testimonies delivered by illustrious men—from Plato and Socrates to Moses and Augustine, and finally to Thomas Jefferson, Patrick Henry, and Lafayette. Turning specifically to America’s involvement in the slave trade, he spoke of how it had deprived Africa of its children and turned men into brutes. But with the passage of the Thirteenth Amendment a month earlier, Garnet now proposed to look forward. He urged “reformers of this and coming ages” to heed the call of the three E’s: “

Emancipate, Enfranchise, Educate.

”

16

A few months later the war ended. The South surrendered at Appomattox, the Confederacy went down in defeat, the Union was preserved, and the Thirteenth Amendment dealt slavery its final blow. Triumph did not last long, however. Lincoln was assassinated and black New Yorkers were devastated. “Men had learned to trust the future of the nation to his keeping,” Robert Hamilton wrote in the

Weekly Anglo-African

.

“We all regarded him as more than equal to any coming emergencies, and in the joy of our hearts were forgetting past afflictions, in the joyous sunlight of a golden peace in which he figured as the great central peacemaker. No matter what course he had chosen, we would have cheerfully acquiesced in it.” It was now up to the people, he concluded, to undertake the enormous task of thinking out “this problem of peace, or rather the principle on which alone peace can safely rest.”

17

Garnet put together a committee, the National Lincoln Monument Association, to erect a Colored People’s National Monument in memory of the slain president. Its membership included James McCune Smith, Frederick Douglass, William J. Wilson, Philip Bell, and yes, George Downing. Eager to create a monument that would endure, Garnet did not want to memorialize Lincoln in the evanescent form of the spoken or written word. Nor did he want a mere physical monument that might also fall victim to the passage of time. Instead, Garnet proposed building a school in the District of Columbia for “the education of the Children of Freemen and Freedmen, and their descendants forever.”

18

His plan never materialized, but a monument commemorating Lincoln was finally built.

It’s not the Lincoln Memorial you’re familiar with—the massive sculpture of a seated Lincoln enshrined in a vast neo-Grecian templelike structure adorned with a peristyle of fluted Doric columns. That monument, located near the Tidal Basin in downtown Washington, D.C., and attracting millions of visitors a year, was constructed much later, between 1914 and 1922.

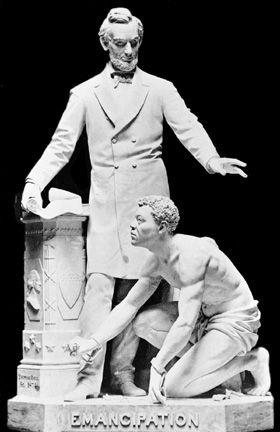

The Colored People’s National Monument stands in the much lonelier site of what is now Lincoln Park in southeast Washington. It depicts Lincoln standing erect beside a whipping post around which swirls a vine. With his right hand, he grasps the Emancipation Proclamation lying atop the post. As if in benediction, his left hand stretches over the body of an unshackled slave kneeling in front of him. The word “emancipation” is carved in large block letters on the base of the pedestal.

The unveiling ceremony took place on the eleventh anniversary of Lincoln’s assassination. Congress declared the day a holiday so that all who wanted could attend. President Ulysses S. Grant was seated on the

platform surrounded by members of his cabinet, Supreme Court justices, senators, and many prominent blacks, including Frederick Douglass and George Downing. Garnet was not with them, and his name was never mentioned.

Abraham Lincoln standing above crouched slave wearing manacles, sculpture by Thomas Ball, between 1875 and 1910 (Library of Congress)

Wounds could not be healed. Garnet never regained his former standing in the black community. He traveled throughout the country, returning to New York in 1870, poor, unhappy, and after the death of his beloved wife, very much alone. A second marriage to Sarah Tompkins proved unsatisfactory, and they separated after a year. For Garnet, there

was only one solution left: emigration. His opportunity came years later when President James A. Garfield appointed him United States minister and counsel general to Liberia. To those who feared for his health, Garnet responded: “Would you have me linger here in old age, in neglect, and in want? … I cannot stay amongst these ungrateful people who have completely forgotten me. No, I go gladly to Africa.”

19

Garnet left for Liberia in November 1881, only to die in February 1882.

George Downing might have gotten the better of his former schoolmate. But it was a hollow victory. An ardent integrationist, Downing was forced to spend the rest of his life fighting to realize the promise of emancipation.

Andrew Johnson succeeded Lincoln in the White House. In February 1866, Downing and a delegation that included Frederick Douglass met with the new president. Downing stated their case in bold and simple terms: “that we are not satisfied with an amendment prohibiting slavery, but that we wish it enforced with appropriate legislation.” In other words, the delegation was demanding black male suffrage as a protection against possible injustice. Johnson’s response was a portent of darker days ahead. As if giving a history lesson, he proceeded to triangulate racial hatred and expose the race and class fault lines that were still tearing the country apart. Masters degraded slaves, treating them as nonhuman property to be bought and sold at will, he explained. In turn, the slave held in contempt the poor white man who was “struggling hard upon a poor piece of land.” And so the poor white man opposed “the slave and his master combined [as they] kept him in slavery by depriving him of a fair participation in the labor and production of the rich lands of the country.” With all of this hatred to go around, Johnson refused to contemplate any measure that would, in his words, “commence a war of races.”