Read Beneath the Sands of Egypt Online

Authors: PhD Donald P. Ryan

Beneath the Sands of Egypt (29 page)

After a couple of days of formalities and organizing logistics, we were able to begin work. We were assigned a smart young inspector, and the valley electricians installed the lights again in KV 21, in whose burial chamber we once more set up our tables and chairs. First on our agenda was to review the state of our tombs. How had they fared in the last dozen years, especially in the wake of the great flood of 1994? We were particularly interested in viewing the crack monitors we had installed in 2003, and we were delighted with the results. There were no signs of any shifting in the cracks, the fine crosshairs still aligned as when we left them. That's not to say that cracks might not be expanding for whatever reasons elsewhere in the valley, but at least our tombs, in the short term anyway, appeared to be stable. Although we found no evidence of major flooding in any of our tombs, there was evidence of some water entering Tomb 21, leaving a very fine layer of silt on the floor of the burial chamber, apparently the result of rainwater pummeling the exterior stairs and running down the corridors and steps below.

I was anxious for Larry to take a look at the objects stored in Tomb 60, and it was exciting to reopen the tomb. I was aware that the tomb had been entered at least once in the last year or so. I saw as much on a

National Geographic

television program during which Zahi Hawass and company explored its interior and marveled at the mummy housed in a wooden case we had built. The tomb, as expected, was much as we had left it, although we were surprised to find something that resembled a human body covered with a sheet lying atop the mummy's box. “Darn that

National Geographic

!” I yelled. “They were too lazy to put the lady back into her box!” Much to my surprise, though, such was not the case. When I pulled back the sheet, there lay another mummy, that of a bald young boy

whose battered chest lay ripped open. I recognized the fellow. He used to reside in the nearby tomb of Thutmose IV, where I had seen him in a couple of different chambers in previous years. Apparently he was moved to KV 60 for safekeeping with the opening of KV 43 to tourists. Our royal woman was still inside, and

National Geographic

was absolved.

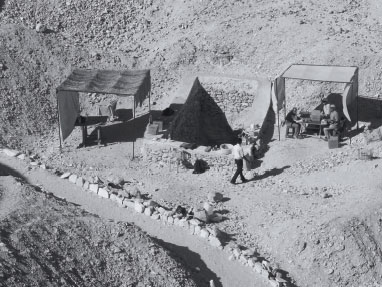

The 2007 field camp outside the entrance of KV 21. The canopies provide shade and a nice fresh-air working environment.

Denis Whitfill/PLU Valley of the Kings Project

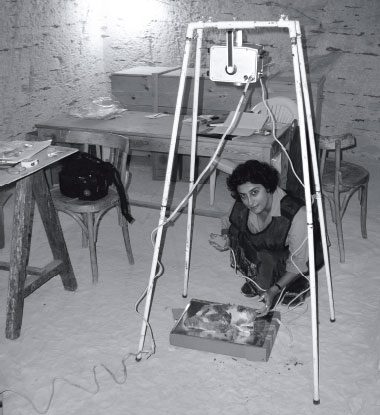

Larry scrutinized many of the artifacts from Tomb 60 and the others, with the informed eyes of a curator who has had a lifetime of experience with a wide variety of Egyptian objects, and Brian was helpful in examining and cataloging our many previous finds. Perhaps the biggest highlight of our new field season was the arrival of Salima Ikram, whose effusive personality has made her the darling of many an international lecture or television appearance. Salima

wrote her Ph.D. dissertation on the topic of meat and butchering in ancient Egypt, a surprisingly fascinating subject with many tangents. She was naturally interested in the several small wrapped mummy packages we had recovered from Tomb 60, whose contents remained unknown. Salima suspected that they were “victual mummies”: preserved birds and chunks of meat that served as food provisions for a tomb's occupant. There was one way to find out. Salima had brought with her a portable X-ray device, which she and an assistant set up with practiced efficiency in the burial chamber of KV 21. True to form, she bubbled with enthusiasm as she knelt down clad in her protective lead apron to position each object and plate of film.

We did not have to wait long for answers. The kind scholars at Chicago House assisted in the development of the X-ray film, and within a day Salima came to my hotel room bearing the results. Holding the exposures up to the light streaming through a sliding glass door, we could see that Salima's suppositions were correct. Revealed there were the little desiccated remains of small birds, wrapped in oval packages, and substantial chunks of meat, still attached to the bone, including an impressive rack of beef ribs.

The return to the Valley of the Kings proved a wonderful success with only a few drawbacks, including some health issues. Much to my surprise, I experienced twelve different afflictions during the month we worked, including the typical predictable illnesses, along with headaches and even a sprained ankle. Apparently, some of the immunity I once believed I possessed had worn off in the years since my last visit. On the bright side, we were working in the fall rather than the summer. It was a very welcome and sensible change from the brutally hot conditions we had experienced during our first four field seasons.

Egyptologist Dr. Salima Ikram operating her portable X-ray unit in the burial chamber of KV 21.

Denis Whitfill/PLU Valley of the Kings Project

In the more hospitable season of fall, there were plenty of other archaeologists around from all over the world working on tombs, temples, and other projects. There was even a bit of a social life, featuring occasional parties, dinners, and lectures, along with informal get-togethers with other Egyptologists. Very generously, Chicago House made its wonderful library available for use by visiting scholars. Overall, I returned home encouraged and excited,

with hopes of future field seasons to come. Not only had my dreams of returning to Egypt been fulfilled, they had far exceeded my expectations.

Just a few months after I left, a startling announcement came out of Egypt. A new tomb had been found in the Valley of the Kings, the first since Howard Carter's discovery of Tutankhamun in 1922. I knew it was coming. My friend Otto Schaden had told me as much the year before. Otto had been working for years clearing the debris out of the lengthy corridors that constituted the Twentieth Dynasty tomb known as KV 10, which belonged to the Nineteenth Dynasty ruler Amenmesses. While digging outside the tomb's entrance, Otto uncovered what appeared to be the edges of a pit and very much looking like the top of a tomb shaft. In what seems to be almost a cosmic tradition in archaeology, the discovery was made just a few days before he was finishing up his field season. A new tomb would surely be an incredible discovery, but there was also an excellent chance that this was just a shallow pit full of rubble, perhaps a false start to a shaft leading to nothing. With such tantalizing prospects, it must have been an agonizing year of anticipation while he waited for the next field season, when the truth would be learned.

A shaft it was, leading to a sealed single chamber packed with seven coffins and numerous sealed white jars. It was an amazing scene to behold, but opening tombs of course soon leads to the reality of dealing with their contents. In the case of this new KV 63, Otto was presented with the horrifying fact that most of these wooden coffins had been chewed nearly to sawdust by termites and were seemingly held together by their painted surfaces. And, incredibly, the coffins held no mummies but contained a strange variety of mummification materials, ancient stuffed “pillows,” floral wreaths, and other funerary equipment.

The situation with the artifacts was a conservationist's nightmare. Otto remained in Egypt for months until the tomb was properly documented with everything in situ. As was the case with the discovery of Tut, official and unofficial visitors, including the press, were a constant distraction, but the tomb's contents were successfully removed to the nearby KV 10 to await further study. What did Otto find? Is it actually a tomb if no bodies are found? Or is it more proper to see it as a cache of funerary objects? Can these objects be associated with individuals known or unknown? Like so much in archaeology, the extent of the answers we seek might never meet our expectations, but even so, mysteries can keep us interested and motivated.

It was another long year of anticipation for me, too, as I prepared my application for another field season. This time I would include archaeologist Paul Buck, who taught me how to wield a trowel during our formative first field experiences in Egypt as graduate students. Paul, unable to accompany me on my very first year in the valley, was now a professor and researcher in Las Vegas, and he was eager to participate. With his vast field experience in Egypt and elsewhere and his hilarious sense of humor, Paul was a very welcome addition to the team. Additionally, Denis Whitfill, a longtime adventure buddy who had worked with me and Thor Heyerdahl on Tenerife, would serve as our photographer and archaeological technician. Larry and Salima would return, and our team would be rounded out by Barbara Aston, whose expertise in interpreting ancient pottery was extremely desirable.

Our focus in 2006 would be the rubble-choked Tomb 27, a daunting task that at least superficially guaranteed no great results from what would be our substantial efforts. It was an intimidating process. Although we had earlier removed some of the upper layers of flood debris in a couple of the tomb's four chambers, there

were literally tons more before we would reach the floors where we expected to uncover whatever was left of the original burial.

On the day we were to begin, our local work crew's documents had not been completely processed, and, anxious to start, Paul, Denis, and I decided to commence excavations without them. A couple days of moving rocks and buckets up a ladder extending down the shaft left us with sore backs and an even greater appreciation for the hard work of our employees who would soon arrive. Eventually the shaft was completely cleared, and we found at its bottom the remains of mud bricks that had originally sealed the tomb's door. The first chamber that followed was reminiscent of the sole room constituting KV 28. There was plenty of modern garbage about, and soot tarnished the doorway and ceiling. Surprisingly, we found very little here, although a suspicious layer of plaster in the floor brought temporary excitement with thoughts of a sealed shaft having escaped the destruction wrought upon the rest of the tomb. Alas, it turned out to be a sort of floor repair squaring up a short ramp leading to a large adjacent chamber we designated C.

Even though encumbered with flood debris, Chamber C was curiously interesting. A channel dug through the dirt leading to a pit nearly reaching the tomb's floor remained from either Mariette's initial probe or from subsequent tomb robbers. Our own test pits in the room's corners to determine its architectural plan had already revealed a small collection of pottery and the skeletal remains of a headless torso. Against one wall, too, was a tall, wide niche with no discernible function, resembling an unfinished start to what in other tombs would be a staircase.

Chamber C would prove to be quite a challenge as we systematically brought the level of debris down to the floor. Here we expected to find whatever might be left of the room's contents, and

in this we were more than well rewarded. Our careful excavation revealed a great mass of pottery, all shattered into a jumbled mess, many of the pots being similar to the large white jars we had examined in the side chamber of Tomb 21. It seemed impossible to determine how many there once were, but by counting the surviving hard mud jar stoppers, we were able to arrive at a number for at least the large pots. There were other types of pottery as well, including little plates and bowls. Though damaged, they would prove to be the key in dating KV 27's use.

The huge quantity of shards was imposing, and we hoped to be able to match up a few vessels at least as a sample. A thick cluster of broken ceramic bits and pieces was examined and collected from a pile against the wall in hopes that we might find a complete collection of joining fragments. To our disappointment, this little deposit contained an almost random selection of shards from several different vessels, but this in itself was quite instructive. It now became easy to imagine what had happened here. The room had been used to store a large number of vessels, including perhaps thirty white pots containing embalming leftovers or grave goods. Piles of dishes, some perhaps loaded up with food for sustaining the deceased, were likewise placed or stacked on the floor. One day a catastrophe happened, on a date that remains undetermined. Either the force of a massive flood broke down the tomb's door or, more likely, the tomb had already been breached, pilfered, and left open, and churning brown water poured down the tomb's shaft, carrying with it rocks and boulders.