Read Beneath the Sands of Egypt Online

Authors: PhD Donald P. Ryan

Beneath the Sands of Egypt (19 page)

My first glimpse of the burial chamber confirmed what Belzoni and the early-nineteenth-century visitors had described: a rectangular room dominated by a single pillar. Along two of its walls were long niches resembling shelves, an unusual characteristic in the valley's many tombs. While the room's white limestone walls, speckled with natural flint nodules, were bare and unprepared for decoration, there were swaths of the ceiling bearing the marks of crack repairs, with the handprints of the ancient workmen still visible in the plaster. The floor was a different matter altogether, it being blanketed with the shattered, randomly scattered, decayed remains of burial equipment. The fine silt on the floor and the stain of a “bathtub ring” from flooding several centimeters deep around the chamber's perimeter told the story. Sometime after the time of Belzoni, the tomb had taken on rain-or floodwater, which turned this room into a slowly evaporating lake and woefully damaged

whatever might have survived. And as for the two women described by Belzoni, I continued to find their body parts here and there. Most disturbing was a pile of hands and feet, gathered together by whom and for what purpose I did not know.

It was necessary to tread lightly as I explored this depressing room and then made my way over to a large square aperture in one wall: the anticipated side chamber. Peering inside, I was relieved to see that the elevated sill of the entrance had protected the chamber's contents from water damage. Unfortunately, other forces of destruction had been at work. The floor of this little room was covered with the well-preserved remains of a couple dozen large, handsome, ancient white storage jars, all shattered, their contents scattered about the floor. A big, heavy rock found in the midst of the shards told the story. It had been intentionally heaved into the mass of pots, perhaps in a spontaneous act of immature delinquency, accompanied by a rare and short concert of shattering intact Eighteenth Dynasty ceramics. Some graffiti on the chamber's ceiling ambiguously suggested a culprit: Scrawled in black, twice, was

ME!

accompanied by the date 1826. Whether these letters are the initials of a certain M.E. or merely a childish self-reference remains a mystery. We do know from the notes of Burton and Lane that the tomb was still accessible at that time, and any number of visitors might have made the descent with the possibility of unrestrained pilfering or vandalism. The torn-up mummies, the shattered pots, and the graffiti certainly demonstrated a profound lack of respect, and yet another agent of destruction, bats, had left deposits of their guano here and there as a kind of final, natural insult.

I clambered out of the tomb and described my experience to Papworth, who had been eagerly awaiting my return above. The two of us visited the interior of the tomb again the next day. Papworth was as dismayed as I was at the natural and human degradation of

the tomb, and we both agreed that KV 21 would be a handful to clear and document. With a reasonable idea about what we might expect to deal with in the future, we installed a metal door, blocked it with stones, and returned our attention to KV 60

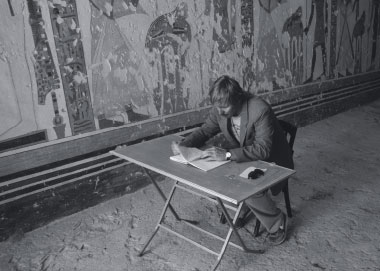

The beautifully decorated Twentieth Dynasty tomb of Montuhirkhopeshef (KV 19) served as our “office” during the first two seasons of fieldwork in the Valley of the Kings.

PLU Valley of the Kings Project

The excitement of that first year in the Valley of the Kings was irrepressible, and I couldn't wait to return yet again, the beastly heat and the array of annoyances forgotten within weeks. Papworth remained excited, and I added others to the team for our second field season, including two students and an art professor from Pacific Lutheran University. The students would be invaluable in piecing together shattered pots and coffin fragments, and the artist, Lawry Gold, would produce exquisite drawings of our rare decorated items. Our small team arrived in Luxor in May 1990 and I

once again set up our office and laboratory in KV 19, the nearby beautiful tomb of Montuhirkhopeshef.

With much of the work in KV 60 completed, our efforts that year were concentrated mostly on KV 21. Additional digging was required to clear off and reveal 21's steps, and the members of our workforce, evenly spaced on the steep incline, passed their baskets, often in rhythm to some of their traditional work songs. It soon became clear that the tomb's ancient exterior steps would need to be protected, as they certainly wouldn't be able to stand the wear and tear that would be exacted upon them as we began to excavate its interior.

Papworth, who possessed the building skills I do not, designed a set of wooden stairs that would fit directly over the originals. The local carpenters, operating from what resembled a medieval workshop, skillfully produced the steps, which fit perfectly and were still intact nearly twenty years later. Papworth likewise would soon order up another set for the interior stairs, which not only preserved their friable limestone edges but were an important safety measure for the constant traffic that would soon materialize as we cleared the burial chamber. I was delighted to discover one day that Papworth had installed a sign on top of these steep steps reading

SPEED LIMIT, 70 MPH, NO PASSING NEXT 2 MILES

.

Another improvement was the installation of electric lighting throughout the tomb. A line of cable was run along the tomb's walls, and, with the help of the resourceful valley electricians, light-bulbs were spliced in at intervals, providing a wonderfully well-lit environment for working. The cable extended for a hundred yards across the landscape, where it was tied into another tomb's electrical system.

As the exterior steps were cleared, the full extent of the doorway, which was mostly blocked with stone, was finally revealed,

and we left the lower courses intact to the level of the sloping debris inside. At one point while I sat on the bottommost step examining the lower blockage, half of the remaining wall collapsed, just barely missing me, and, curiously, in its wake were revealed specks of gold flake, which, as in the case of KV 60, were likely residue from the work of ancient robbers.

The first corridor was readily cleared, with only a few objects found within the debris, including a crude servant or

ushabti

figurine characteristic of the time of Rameses VI. Given that everything else about the tomb screamed Eighteenth Dynasty in date, this Twentieth Dynasty intruder must have come in with the exterior debris, a phenomenon not uncommon in the valley.

From an archaeological standpoint, the second staircase and corridor were easy to deal with, the operation being mostly an exercise in removing a lot of stones either in baskets or individually on the shoulders of the sturdy workmen. The burial chamber, though, was another matter altogether. The floor was photographed and sketched and then the larger rocks removed. As in Tomb 60, Papworth measured out a grid of one-meter squares around the room using a spool of string and numbers marked on little slips of paper. Thus prepared, we addressed each square systematically in its turn, often seated in an adjacent, cleared spot or on our knees. With a brush, a dustpan, and a basket, any objects were collected and noted.

It was actually a grueling task. Despite the fact that we were well underground, the temperature was often over ninety degrees Fahrenheit, slowing us down and contributing heavily to lethargy. More serious was the poisonous combination of the fine silt on the floor mixed with the pungent debris of bat guano. Dust masks were not readily available, and even when we had them, they made breathing so uncomfortable that they were often ignored. I

preferred a cotton scarf wrapped over my mouth, but even that proved stifling in such conditions. The result was that twice during our clearance of KV 21, I awoke in my room at night with a severe and terrifying respiratory attack, my heart racing and my survival until daylight questionable. Fortunately, a large dose of asthma medication seemed to do the job, and the lesson was learned. All future tomb excavations would thereafter require dust protection.

Safety on our projects is of course always a priority, and although it was easy to talk our team of foreigners into taking various precautions, it was another thing to convince the local workmen. Some refused to wear shoes, even when swinging their heavy hoes precariously close to their bare feet, and the inevitable occurred on occasion. The effects of the substantial heat, too, were always a worry, and many of the workers preferred their heads bare. Part of that problem was solved by the issuing of baseball caps that were gratefully provided by Quaker Oats, then the makers of Gatorade. The previous year I had brought a few packs of powdered Gatorade with me to the valley, and when an Egyptian colleague passed out from the heat, we brought him to a cool place and mixed him up a small batch, which proved very effective in his revival and rehydration. When I returned home, I wrote a small testimonial to the company in hopes of obtaining a few free samples. I didn't hear from them for months, until one day a truck appeared in my driveway and unloaded ten fifty-pound boxes containing large bags of the powdery substance. Five hundred pounds of Gatorade, perhaps enough to flavor a large swimming pool, accompanied by about a dozen hats with the product logo.

Obviously, we wouldn't be able to take the whole lot with us to Egypt, but I did distribute a number of the bags to my digmates to carry and also took the hats, which became a sort of collector's item. One of my workmen, a gentleman from the village who was

probably in his mid-sixties, had apparently given or traded away his cap and pleaded for a new one with a ridiculous story that could easily have been concocted by a crafty ten-year-old. A small mouse, he claimed, came into his house at night and carried it away. His tale was so seriously and dramatically presented, complete with hand gestures and expressions of surprise and dismay, that he had me laughing hard. He got a new hat. And the company generously furnished me with more the following year.

The supply of Gatorade would last for years, and the workmen, with their well-developed sweet teeth, would occasionally mix it up in an earthen jar until it resembled a viscous syrup, which they claimed was utterly delicious. Some of my team had a difficult time watching as the green goo oozed out of the jar into clear cups cut from the plastic bottoms of mineral-water bottles. Nonetheless, our more diluted version of the drink served us well, its lemon-lime flavor greatly facilitating our consumption of the large quantity of liquids necessary to survive in such heat.

Despite the hardships, we managed to clear the floor of Tomb 21's burial chamber, which was frustratingly sparse in any artifacts that might shed light on the tomb's occupants or even the nature of their burial provisions. A few painted fragments of wood could be matched together, including some that bore the text of a routine funerary inscription. Par for the course in our experience, the portion of the inscription that would normally contain the name of the deceased was not present. As in the case of KV 60, no artifacts in the tomb would reveal the identities of its owners, except in the broadest of terms.

The little side room was both a treat and a nuisance. Working in its relatively tight confines was a bit of an annoyance, and the reality of the shattered pots all around was dismaying. The pots' contents were strewn about the floor, and, interestingly, much of

those contents seemed to be soiled linen rags and little tied-up bags of natron, the white dehydrating agent used in the mummification process, no doubt leftovers from the embalming of the tomb's occupants. Within the mix were several seals bearing the stamp of the royal necropolis: a recumbent jackal poised over nine bound captives, representing the traditional enemies of Egypt. They had once been used to seal some of the large pots, whose style established the date of the tomb's use between the reigns of Hatshepsut and Thutmose IV in the Eighteenth Dynasty.

Mark Papworth had the gruesome task of dealing with what was left of the two women. In a strange procession that included a box of hands and feet, a linear plastic bag containing leg and arm pieces, and two cartons, each containing a torso, the workmen transferred the various bits and pieces from Tomb 21 to a large table set up in KV 19. Papworth was barely fazed. His years of viewing such things as a coroner and crime-scene investigator, though usually with fresher material, of more recent vintage, had prepared him for performing the inevitable sorting of the body parts. Each component was laid out and then matched with other fragments. The end result was unpleasant. One had a tragically damaged face and a bashed-in chest cavity, and the other was missing its head. And all that was left of the long hair Belzoni described were a few curly locks. One of the mummies smelled like dirty socks.

Intriguingly, the left hand of each of the women was clenched in a manner that some would argue is characteristic of a royal female pose of mummification, much like the mummy in KV 60. Papworth was convinced, too, that when the flesh and wrappings of the left arm of one of the mummies was articulated with its fragments, it was bent at the elbow. This is a clue that might address one of the many big questions in Egyptian archaeology: Where

were all the burials of the many known women from the Eighteenth Dynasty and other eras of the New Kingdom? Could some of them have been buried right under everyone's noses right there in the Valley of the Kings? The name “Valley of the Kings” is actually a later Arabic appellation and doesn't define its complete history. We already know that a few royal family members and favored friends or officials were also buried there.