B008AITH44 EBOK (54 page)

Authors: Brigitte Hamann

And in another poem, “Titania’s Spinnlied” (Titania’s Spinning Song), some very similar lines occur.

Du willst ein Spiel der Minne,

Verrückter Erdensohn?

Mit goldnen Fäden spinne

Dein Leichentuch ich schon….

In meiner schönen Mache

Verzapple dich zu Tod,

Ich schaue zu und lache

Von jetzt bis Morgenrot.

[You want a game of love, / Mad mortal? / With golden threads I am already / Spinning your shroud…. / / In my handsome net / Enmesh yourself until you die, / I stand by and laugh / From now until dawn.]

But in spite of threats of suicide, Alfred had no real intention of becoming a corpse. Instead, he demanded money from his idol. For this, too, Elisabeth had only scorn.

Ich glaube nicht an die Liebe,

Was dir dein Leben vergällt,

Das sind ganz andere Triebe,

Ich ahne wohl was dir fehlt.

Mein Jüngling, du hast wohl Schulden

Und wähnst in schlauem Sinn:

Die Liebe mit goldenen Gulden

Lohnt mir meine Königin.

29

[I do not believe in love, / What is souring your life / Are quite different urges, / I truly sense what you need. / My boy, surely you have debts / And imagine slyly: / My queen will repay me / My love with golden guldens.]

This farce of “Titania and Alfred” is not as trivial as it may at first glance seem in the context of a biography. It characterized Elisabeth’s relations with her admirers, as well as her inability to separate reality from fantasy. The fact that she spent many hours composing the Alfred poems shows the extent of her isolation.

The episode with Alfred Gurniak took place in 1887–1888, a time of crises in the Balkans and the constant threat of war, a time when the European system of alliances was changing in fundamental ways through the Reinsurance Treaty between Germany and Russia, concluded behind the back of Austria-Hungary. During this time, two men politically close to the Empress—Gyula Andrássy and Crown Prince Rudolf—voiced opposition to the Emperor’s foreign policy. Both expected and hoped for backing from the only person whose word could have gained the Emperor’s ear—the Empress. Elisabeth evaded all expectations and all hopes. She abandoned both Andrássy and Rudolf, just as for decades she had abandoned her husband with his problems. She showed the world her contempt—and concentrated on the jest of infatuated Alfred from Dresden.

The tragedy of Crown Prince Rudolf was coming to a head. Elisabeth was so caught up in her reveries of Titania, Queen of the Fairies, and various besotted asses that she did not even acknowledge her son’s

unhappiness,

though repeatedly, with extreme shyness and caution, he asked for her help.

*

The seductiveness of Elisabeth’s personality outlived even her beauty. In the 1890s, when her skin had long since become wrinkled and her sight had grown blurred, she still, when she made the effort, exerted her usual magic. The young Greek readers who accompanied her during these years fell in love with the solitary, melancholy woman, and for the rest of their lives they raved about the hours they had been allowed to spend in her company. Konstantin Christomanos, for one, wrote gushy and lyrical books about her. The people around Elisabeth, however, felt sorry for these young men. Chief Chamberlain Nopcsa wrote to Ida Ferenczy that the Empress was spoiling the Greeks “in a way I have never yet witnessed in Her Majesty. Pity the young man, since he will be made unhappy.”

30

Even Alexander von Warsberg, who at the outset had been very critical of the Empress, gave clear signs of love after only a short time of traveling in Greece with her.

It hardly needs repeating that Emperor Franz Joseph’s love for his wife remained constant through all the years, in spite of everything.

1

. Festetics, October 15, 1872.

2

. Ibid., February 6, 1872.

3

. Ibid., June 21, 1878.

4

. Ibid., January 21, 1875.

5

. Ibid., February 6, 1874.

6

. Corti Papers, from Budapest, April 14, 1869.

7

. Ibid., from Gödöllö, April 30, 1869.

8

. Ibid., January 31, 1867.

9

. Ibid., December 18, 1868.

10

. Ibid., September 6, 1868.

11

. Ibid., January 1870.

12

. Ibid., July 8, 1868, and June 22, 1867.

13

. StBW, manuscript collection, Friedjung Papers, Interview with Marie Festetics, March 6, 1913.

14

. To her niece Amélie, Valerie, September 3, 1908.

15

. Wallersee,

Vergangenheit

,

pp. 93f.

16

. Quoted here from Pacher’s reports, contained in Corti Papers. A slightly different version appears in Corti,

Elisabeth,

pp. 254ff.

17

. Elisabeth,

Nordseelieder,

p. 96.

18

. Corti,

Elisabeth,

pp. 350f.

19

. Elisabeth,

Nordseelieder,

p. 61.

20

. Elisabeth, manuscript. Already in Corti,

Elisabeth

,

pp. 384ff.

21

. Festetics, January 9, 1874.

22

. Marie Louise von Wallersee,

Kaiserin

Elisabeth

und

ich

(Leipzig, 1935), pp. 60ff.

23

. Ibid., p. 59. A longer and weaker version of this poem in Elisabeth,

Winterlieder,

pp. 206–9.

24

. Hübner, May 23, 1876.

25

. Wallersee,

Elisabeth

,

p. 202.

26

. Konstantin Christomanos,

Tagebuchblätter

(Vienna, 1899), pp. 98–9.

27

. Elisabeth,

Nordseelieder

,

p. 59.

28

. Valerie, September 4, 1891.

29

. These lines and the compilation “Titania und Alfred” are in the unpaginated manuscript section of the literary bequest in Bern.

30

. Corti Papers, from Barcelona, February 6, 1893.

*

This refrain alternates with every one of the following lines.

CHAPTER TEN

T

he more Elisabeth’s tendency to withdraw from the world and her fear of people increased, the more closely she became

attached

to her cousin King Ludwig II of Bavaria, who had turned out very like her. The relationship between the two had not begun as a particularly close one. There had been significant quarrels, rooted in family relations; the rivalry between the royal and the ducal Bavarian lines was generations old. The kinship was not very close: Ludwig’s grandfather, King Ludwig I, and Sisi’s mother, Ludovika, were brother and sister, making Sisi the cousin of Ludwig’s father, King Max II. The eight-year difference in their ages played a large part in their early years; when Elisabeth left Bavaria in 1854 at the

age of sixteen, the then Crown Prince Ludwig was only eight years old.

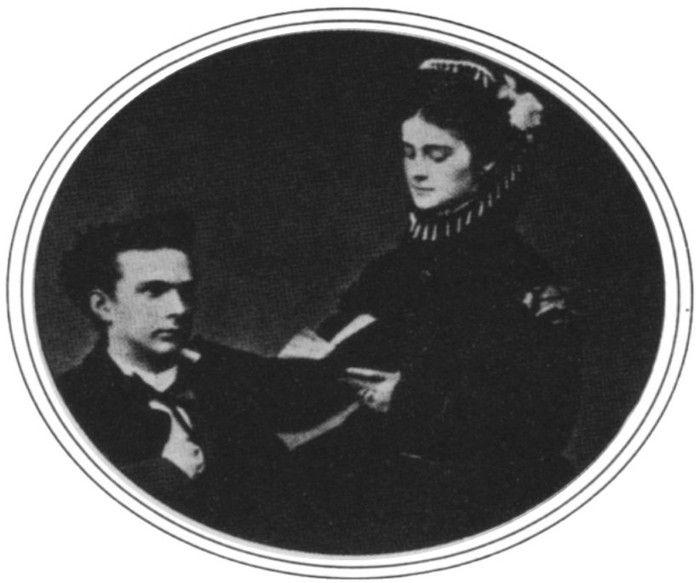

Ten years later, Ludwig became King. From approximately this time on—Ludwig was eighteen, Elisabeth twenty-six—they grew closer. Shortly after his accession in 1864, the young King visited his imperial cousin in Bad Kissingen, where he remained for some time, going on walks with her and talking with her so intimately and in such detail that Sisi told her family, “delighted by their being in unison, of many shared hours”—making her favorite brother, Karl Theodor (“Gackel”) jealous.

1

Elisabeth and Ludwig attracted attention wherever they went. The young King was exquisitely beautiful, tall, serious, with a romantic flair; beside him, his Wittelsbach cousin, in full bloom, tall and slender, slightly sickly and melancholy. Ludwig’s effect on the court at Munich was much like Sisi’s in Vienna. According to Prince Philipp zu Eulenburg, he

strutted,

“handsome as a golden pheasant, among all the domestic hens.”

2

Both Ludwig and Sisi felt contempt for their world and indulged themselves in ever new eccentricities to shock those around them. Both made their likes and dislikes extremely plain, especially Ludwig. When, for example, he had a guest whom he did not like, he had huge bouquets of flowers placed on the table, so as not to have to look at the miserable wretch.

3

The guest, for his part, had to make desperate efforts to make himself heard.

Both loved solitude and hated court constraints. The following sentences by Ludwig II could just as easily have come from Elisabeth’s pen, except that Munich, and not Vienna, was meant. “Shut up in my golden cage … Can barely wait for the arrival of those blessed days in May to leave for a long time the hated, accursed city to which nothing ties me, which I inhabit with insurmountable loathing.”

4

Elisabeth, too, liked to act unconventionally and irritated the rigidly conformist people around her with unusual expressions, often to such an extent that some concluded that she, too, was at the very least “peculiar,” like her Bavarian cousin. Marie Larisch:

In many things the Empress was very like Ludwig II, but unlike him, had the mental and physical strength not to fall prey to eccentric ideas. She was wont to say, half seriously, half joking: “I know that sometimes I am considered mad.” As she spoke, she wore a mocking smile, and her golden-brown eyes flashed like heat lightning in restrained mischievousness. Everyone who knew Elisabeth well wrote about her pleasure in teasing

innocents.

Thus, with the straightest face, she could sometimes say the most outrageous things or, with an enchanting smile, throw

an elegant indiscretion at someone, in order, as she put it, to enjoy her listener’s gape. Unless you knew Elisabeth through and through, it was sometimes hard to decide if she was saying something seriously or was only joking.

5

Prince Eulenberg also pointed out shared traits.

The Empress, who had a tendency to be somewhat eccentric and who was very talented, always had more understanding for her cousin than other mortals. Considering that she would work for hours in her salon at the trapeze, wearing a kind of circus costume, or would suddenly—attired only in a long rain skirt over jersey clothing—walk from Feldafing to Munich, a

distance

of about 50 kilometers (I encountered her once so attired), it is understandable why she found her cousin’s extravagances ‘reasonable’; his worst excesses surely never reached her ears.

6