Avoid Boring People: Lessons From a Life in Science (40 page)

Read Avoid Boring People: Lessons From a Life in Science Online

Authors: James D. Watson

Tags: #General, #Biography & Autobiography, #Personal Memoirs, #Self-Help, #Life Sciences, #Science, #Scientists, #Molecular biologists, #Biology, #Molecular Biology, #Science & Technology

In the fall of 1975, I resumed teaching at Harvard, flying up to Boston to spend Sunday and Monday nights at the Harvard Faculty Club. My lectures on tumor virus and animal cells were updated versions of those I had given three years before, using as a text the Lab's monograph

The Molecular Biology of Tumor Viruses.

This was to be the last course I would teach at Harvard. Matt Meselson was unwilling to appeal to the dean for an exception to Harvard's long-standing prohibition against sharing faculty with other institutions. And so I was informed that, as of July 1,1976, I would no longer be a professor at Harvard. It was a situation of my own making, but all the same I was much annoyed, if not insulted, since Jack Strominger had recently become director of research at the Dana Färber Cancer Institute across the river while retaining his professorship in our department. Jack, moreover, now was being paid by both institutions, while I would have been content with only one salary if I could keep both jobs. There were many things I knew I would miss about Harvard, but by far the first would be its students; the obligation to lecture to them forced me to extend my own thinking, and occasionally the most extraordinary ones came down for research at Cold Spring Harbor, enriching the intellectual fellowship there.

Just after Christmas, I flew to the West Coast with Liz, Rufus, and Duncan for a two-week visit that started in southern California, where for a week we stayed in an apartment on California Avenue just west of Caltech. There Max Delbrück had arranged for me to give a lecture honoring the recently deceased Jean-Jacques Weigle. I had always enjoyed Jean's nimble brain both at Caltech and when visiting him in his hometown of Geneva, where he did phage experiments in the summer. Afterward we drove up to San Francisco, where W. A. Benjamin held a book party to mark the appearance of the third edition of

The Molecular Biology of the Gene.

Like the first and second editions, its sales over five years would approach a hundred thousand copies.

Then working at Cold Spring Harbor developing a powerful new way to clone genes was the thirty-two-year-old Tom Maniatis. His highly innovative experiments at Harvard as a postdoc with Mark Ptashne had led to his recent appointment as assistant professor. Initially he was to come to Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory for only a year for work, returning to Harvard upon its building of facilities for animal cell experimentation. In collaboration with Argiris Efstratiadis of Fotis Kafatos's Harvard lab, Tom was using messenger RNA molecules from red blood reticulocytes as templates to make full-length double-stranded DNA copies of the ß globin gene. No biohazard possibilities could arise from such experiments, so despite the recombinant DNA moratorium, Tom and his four young collaborators were able to move full steam ahead in their Demerec Laboratory space.

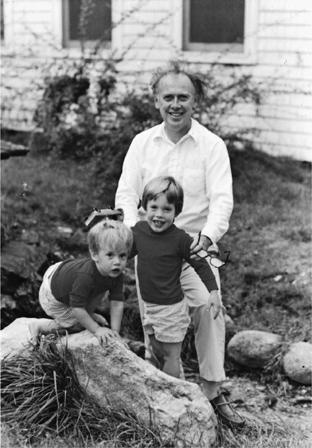

With Rufus (right) and Duncan in 1973

By then, his well-directed intelligence had also caught the attention of Caltech's biology department. Caltech let Tom know it was prepared to make him a tenured member of its faculty. Upon learning this, Mark Ptashne got BMB to ask Henry Rosovsky to move quickly in assembling an ad hoc committee and win approval to offer him a tenured associate professorship. In February I went back to Harvard to attest to Tom's accomplishments before Derek Bok. As expected, Tom was approved.

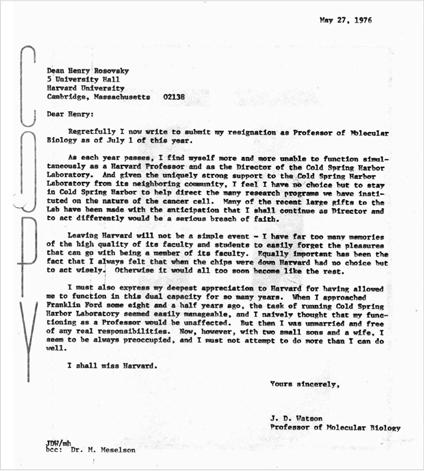

Resignation…

The worry for Harvard all too soon became the possibility that Tom might choose to accept Caltech's offer anyway. The ever more vocal in-house opposition to recombinant DNA experimentation within the Biological Laboratories was hardly an inducement to prefer Harvard. The newly appointed assistant professor Ursula Goodenough and George Wald's wife, Ruth Hubbard, also a scientist, were claiming recombinant DNA experimentation using

E. coli

might put the women in the Bio Labs at risk of cystitis. Both should have known that over the past ten years live

E. coli

cells had been regularly ground up by the pound by men and women alike without a single case of illness.

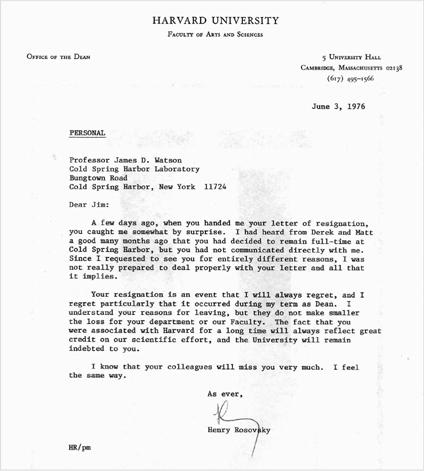

…and response

Initially Mark and Tom did not worry, knowing that Henry Rosovsky was not one to be intimidated by such nonsense, whose source was mainly left-wing elements that had been gaining ground on campus ever since the occupation of University Hall, and which after Vietnam had been further energized by Watergate. It did not matter to Rosovsky that at a public meeting in late May more students had been moved by the rhetoric of Richard Lewontin, Harvard's population geneticist, railing against future capitalistic exploitation of DNA research than had been stirred by my pleas to get on with cancer research using recombinant DNA. Henry Rosovsky sided with scientific progress and gave Harvard scientists the go-ahead to continue the controversial research. So Harvard's “science for the people” leaders took their case to the Cambridge City Hall and its populist mayor, Alfred Vellucci, always keen to put the Harvard elite in their place. At George Wald's urging, he and his fellow councilmen held hearings on June 27 and July 7, 1976, after which they voted for a three-month moratorium on recombinant DNA research within Cambridge city limits. Tom now felt going back to Harvard would be to enter a state of chaos, and so he accepted Caltech's offer, as feared.

Before reaching that decision, Tom had seen me very angered by Harvard for very different reasons when I appeared in his Cold Spring Harbor lab late in the evening directly following my return from several days in Cambridge. Derek Bok had invited me to his office in Massachusetts Hall, and I was expecting that Harvard would bid me farewell in some meaningful way. But for my presence at the Biological Laboratories for the past twenty years, its science would have commanded much less attention from the outside world. Wally Gilbert might very well still be a physicist, while Matt Meselson, and likely also Mark Ptashne, would be teaching in California. To my dismay, Derek's goodbye was entirely perfunctory, giving not a hint that my departure was any loss for Harvard or any detriment to its future.

At the start of June, I flew back to Boston for my last visit to University Hall as a member of its faculty. That afternoon, Henry Rosovsky and I tried hard not to focus on the fact that I was soon to be gone. It was easier to talk about George Wald's pretentious irresponsibility in opposing recombinant DNA. After twenty minutes of not wanting to say goodbye, I thanked Henry for trying so hard to get Harvard on the animal cell bandwagon. If I had not become irreversibly committed to Cold Spring Harbor, together we would have won. Realizing it was almost time for his next appointment, Henry, to my surprise, revealed that in looking over my salary history he noticed that I had always been paid too little. It was his way of saying he liked me. He and I knew that I would be sad walking out of Harvard Yard that day. Even I was not entirely immune to the old chestnut that there is no life after Harvard.

Remembered Lessons

1. Avoid boring people

Never make dull speeches that easily could be delivered by someone else. Predictable words naturally compel audiences to tune out and lock their pocketbooks. Just as tedious is bringing small groups of busy people together for committee meetings with no opportunity for them to offer real input. This is on a par with holding meetings where talk is not followed by meaningful decisions. In both circumstances, committee members will likely soon stop attending gatherings they know will be a waste of their time. Not boring others, of course, requires that you take pains not to become boring, as often happens when you begin to bore yourself. A leader's mind must continually be reconfigured through exposure to new patterns of acting and thinking. Reading the same papers and magazines as everyone else around you is not likely to make you an interesting dinner guest, let alone alter your consciousness. In my case, a subscription to the

Times Literary Supplement,

courtesy of my father-in-law, made me more interesting to sit beside than someone whose diet was limited to

Time, Newsweek,

or the

Economist

—or

Nature

for that matter.

2. Delegate as much authority as possible

Administrators, like scientists, do their jobs best when left alone to do them, freed of the irksome impression of simply carrying out someone else's will. My growing avoidance of micromanagement left me always available to give advice about matters that were not obvious. On learning how my staff wanted to proceed, I generally gave them a go-ahead. Few mistakes were made that closer oversight might have avoided.

3. Institutions are either moving forward

or they are moving backward

There is no downtime in the management of high-powered science. New ideas or techniques need to be quickly exploited before scientists elsewhere do experiments that your people could have done first. Success automatically creates the need for new personnel and facilities that often require new buildings. If you are not ever agile in moving forward, the consequences will go beyond losing credit for the next breakthrough; top staff will move elsewhere to get the resources and support required to maintain their own leadership roles in their respective disciplines. As in sports, last year's championship doesn't count at the end of this season. Therefore, never be or expect other scientists to be sentimental about institutions. Going down with the ship is nuts.

4. Always buy adjacent property that comes up for sale

An institution's growth inevitably demands expanding the size of its campus. Therefore, never hesitate to buy land abutting yours even if there is no immediate use for it. Though the seller will charge you a premium knowing that land is worth more to someone with an adjacent lot than it is to a third party, your bargaining power is still greater than it will be when space is a dire need. It pays to overpay a little now rather than wait till your neighbor has you over a barrel.

5. Attractive buildings project institutional strength

Sometimes it seems money could be saved by building facilities that are less extravagant, with cheaper materials and unknown architects. This, however, is bad for business in the long term. Donors to Harvard never need fear that a building with their name on it will one day be sold off to stanch a hemorrhaging negative cash flow. Less than sturdy structures give out messages that their institution's life may be equally short. In contrast, solid, stylish buildings give donors the confidence that their descendants will one day bask in reflected glory. The lure of permanence inspires generosity.

6. Have wealthy neighbors

Research grants, no matter how much overhead they cover, are never enough to meet immediate needs. Unlike universities that can depend upon rich alumni, research institutions must have rich neighbors nearby who are inclined to take pride in local accomplishments. Typically their enthusiasm will be proportional to the research effort's potential to alleviate human misery. Nothing attracts money like the quest for a cure for a terrible disease.