Avoid Boring People: Lessons From a Life in Science (34 page)

Read Avoid Boring People: Lessons From a Life in Science Online

Authors: James D. Watson

Tags: #General, #Biography & Autobiography, #Personal Memoirs, #Self-Help, #Life Sciences, #Science, #Scientists, #Molecular biologists, #Biology, #Molecular Biology, #Science & Technology

Over the fall months, she had increasingly continued to forgo evening meals at Moors Hall to join my father and me for supper at the Hotel Continental. Upon his return from Martha's Vineyard in August, Dad had chosen to move into the hotel, leaving his apartment at 10

1

/

2

Appian Way. It would save him the trouble of shopping, preparing meals, and tidying up. At the time I did not let on to Dad how my affection for Liz had increased over the past eighteen months. I knew he would worry that at nineteen she was likely to reserve her true affection for someone much closer to her own age.

As soon as I put down Betty's call, I asked Liz to stay with me for supper at the Continental. I did not want to be alone. It would be our first dinner together by ourselves. Afterward she did not go back to her dorm, telling me she did not want me to be alone that evening any more than I did. The next afternoon she left my office early to go grocery shopping on Brattle Street, planning to cook dinner that evening on the antique stove in my Appian Way flat. She had brought school-books to read after dinner in the unheated alcove off the main room. The next night, when again we went together to Carl and Anne Cori's home for dinner, Anne knew she no longer had to find single girls to sit next to me.

Early the following morning, I left Liz to fly to Sarasota to collect a now very apprehensive Dad and bring him by plane to my sister's home in Washington. In 1964, after resigning from the CIA, her husband, Bob Myers, founded

The Washingtonian

magazine with his University of Chicago roommate Laughlin Phillips. Bob was its first publisher and Laughlin the editor. Just recently, Bob had become publisher of the

New Republic,

but too late for Dad, long a faithful reader, to take anything but a brief pleasure from seeing his son-in-law help run his favorite magazine of liberal politics.

Upon my return to Cambridge, I found myself all too soon scheduled to leave Liz again for the annual American Cancer Society (ACS) get-together of scientists and science journalists, this time being held in La Jolla, to the north of San Diego. Out of this meeting, it was hoped, would emerge optimistic press coverage to kick-start the ACS annual fund drive. Several months before, I'd eagerly accepted the invitation to attend, believing the meeting would help me focus on how to start up tumor virus research at Cold Spring Harbor. As it was to be held just before Harvard's weeklong spring break, there was also the possibility of Liz's joining me there after the conference.

To appear as a couple on a trip without causing a scandal, however, it would be necessary for us to marry immediately after Liz's arrival in California. Happily, she had no qualms, instantly accepting my proposal that we effectively elope. We decided not to let anyone know except for her parents in Providence. In the end, the only other person at Harvard in on our plan was my secretary. She found out when Liz came in saying this would be her last day of work. Susie said that Dr. Watson would be much disappointed. Liz replied that, in fact, he wouldn't be disappointed at all.

Before flying west I called Sylvia Bailey, the English-born secretary of Jacob Bronowski, the English polymath hired by the Salk Institute upon Leo Szilard's death, for advice about how Liz and I could best get wed in California. To my surprise, she called back the next day, saying that it would be faster to arrange a church ceremony than a civil ceremony before a justice of the peace. If I gave her the go-ahead, she would contact her friend the Reverend Forshaw, whose Mission-style church was in the center of La Jolla. In turn, Liz went with her mother back to Bonwit Teller's, this time no longer just looking but ready to bring home several outfits appropriate to the occasion and the many photographs we would take to send to relatives and friends by way of announcement.

At the ACS science writers’ gathering, I spoke at length to Bob Rein-hold, a former

Crimson

editor, now writing about science for the

New York Times.

In the article he soon wrote about my plans to turn Cold Spring Harbor toward cancer research, he remarked on the nervous way I held my can of Coke, having no way of knowing that this was no garden-variety tic but the anxious anticipation of my wedding the next evening. My nervousness disappeared as soon as Liz came off the plane. Her smile would always make me feel good. Shortly, we drove north of La Jolla to get a marriage license that would permit us at 9:00 P.M. on March 28 to be wed in the La Jolla Congregational Church. That I was not a churchgoer was of no concern to Reverend Forshaw, whose library prominently displayed one of Bertrand Russell's thicker tomes.

Upon our return to the La Valencia Hotel, we had an early supper at its Whaler's Bar before going on to Jacob and Rita Bronowski's one-story glass house in La Jolla Farms near the Salk Institute. Its stylish ambience was much better suited to wedding photos after sunset than was the church. Afterward, Liz met my small circle of La Jolla friends, who came to the La Valencia for a surprise party without knowing its purpose. We spent our first night as a married couple in one of the rooms looking out on the Pacific Ocean.

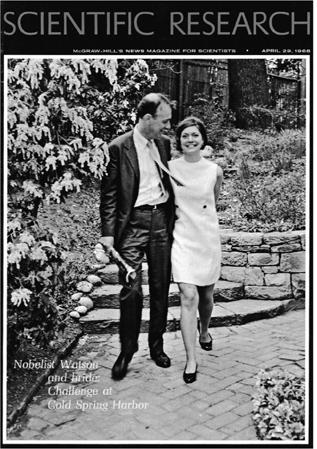

Liz and I on our wedding day, March 28,1968, in La Jolla, California

The next morning we telephoned my sister to tell her and Dad the news and to let them know that we would stop off in Washington on our way back to Harvard. I went to find postcards to let friends such as Seymour Benzer and Paul Doty know that “a nineteen-year-old was now mine.” After a leisurely lunch, we drove east to see the desert plants blooming around Borrego Springs. We spent the night at Casa del Zora before driving through the Anza Desert to the Imperial Valley and from there to the village of San Felipe, some seventy miles south of the Mexican border. There we spent two nights in a hotel catering to fishermen, taking care not to get sunburned while spending much of Sunday swimming in the already warm waters of the Gulf of California.

Unknown to us was Lyndon Johnson's sudden decision to make a major address to the nation that evening. Only after we were back on the U.S. side of the border, driving across southern Arizona, did we learn that the night before, Johnson had announced he would not seek reelection. We hoped he would get us out of the quagmire in Southeast Asia before his term ended, but it seemed a vain hope. Though Johnson then presented the Tet offensive as a big setback for the Viet Cong, he had to believe otherwise, else he would not be stepping down.

By nightfall we were outside Tucson. The next day we admired thousands of tall cacti on an early morning walk in the Saguaro National Park. Dropping off our rented Ford Mustang at the airport, we caught the plane for Washington. Spring was in full bloom, allowing everyone at Betty's house, next to Glover Archibald Park, to half ignore Dad's awful prognosis as Liz and I shared the details of our wedding and the days afterward. Unexpectedly on hand was a photographer sent by McGraw-Hill's new magazine

Scientific Research.

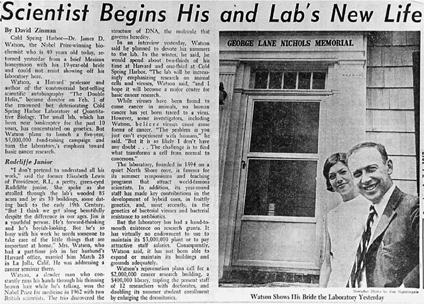

Its forte was fast-breaking stories about scientists as well as science itself. Word that I had just married was already about, and they wanted a picture of Liz and me. The resulting photos revealed Liz a photographer's dream, and we were to be seen together on the cover of the April 29 issue.

The next morning we drove north for four hours to Cold Spring Harbor to see our eventual home. From Washington, I had let John Cairns know of our impending day trip, and the Lab arranged a special welcome dinner prepared by Francoise Spahr. Her husband, Pierre-Francois, was over from Geneva for six months to work with my former Harvard student Ray Gesteland, whom John Cairns had recruited to the lab staff a year earlier. But by the time we gathered in the main room of the big Victorian house at the Lab's entryway, the news of our marriage was eclipsed by horrid events elsewhere. In Memphis, an unknown assassin had just killed Martin Luther King Jr. Before driving off to Providence the next afternoon, Liz and I were interviewed separately by a reporter from Long Island's leading newspaper,

Newsday.

To her dismay, he wound up suggesting in the article about us that her Radcliffe education would effectively lead her to a life of darning my socks.

Liz and I graced the cover of Scientific Research on April 29,1968.

At Liz's home, I met her father, a physician, whom I discovered to be, like my father, a keen reader and skeptic. In this important way, Liz and I had similar upbringings. Though her parents sent her to Central Baptist Church, its chief attraction to them was the music—Providence's best. That evening, my eyes kept drifting to the TV set and its images of the widespread race riots in the wake of the King assassination. The assailant was still unknown.

The next morning, April 6, was my fortieth birthday, and were it not for Liz by my side I would have been feeling sadly old. We pushed on toward Cambridge just before noon to give Liz time for a Saturday afternoon of housewares shopping in Harvard Square. Her first big purchase was an ironing board that I carried back from Dixon's Hardware. Later enriching our Appian Way flat was a second silver candlestick, a gift from the Society of Fellows to complement the one given to me upon my becoming a senior fellow. Another early purchase was a big cookbook by Julia Child, a local resident, which Liz bought upon the suggestion of the woman at the Radcliffe registrar's office who recorded the change of Liz's name from Lewis to Watson. Its recipes proved much more satisfying to Liz to master than those in her organic chemistry class. Inevitably my days as a beanpole were soon to end.

The Newsday article, April 6,1968

As soon as Liz had taken her final exams, we made the five-hour drive down to Cold Spring Harbor, where the Lab had rented a house on Shore Road to let Dad live with us over the summer. He had been hospitalized several times while with Betty but now was pain-free enough to move in and out of our rented four-door Dodge. The new car spared Liz having to master jump-starting my MG TE The day after we arrived, another multicourse meal, this time featuring lobster américaine, was cooked by Francoise. While eating it, we were horrified to learn that Robert Kennedy had just been shot dead in Los Angeles. I had pinned my hopes on him to win the Democratic nomination for president. Not since World War II had daily life been so frequently overshadowed by such a string of woeful events.

Nancy and Brook Hopkins began coming over to our Shore Road home to keep Dad company. Nancy was down for the summer with more than a dozen graduate students from MIT and Harvard, all focused on phage λ, working together in the vacant lab space underneath that of AI Hershey. Also about were Max and Manny Delbrück, back for Max's fourth consecutive year of teaching a course in the Animal House on the photosensitivity of the mold

Phycorny ces.

Instantly I sensed their approval of Liz, and relief that I no longer would suffer from chronic restlessness. Over July, Dad's condition worsened to require a twenty-four-hour home nurse. The chemotherapy he was receiving from the Lab's local doctor, Reese Alsop, was mainly palliative. By month's end, however, the pain proved too great to treat at home, and he was admitted to Huntington Hospital before being settled in a nearby nursing home. He would pass only a night there before pneumonia mercifully ended his agony.