Avoid Boring People: Lessons From a Life in Science (23 page)

Read Avoid Boring People: Lessons From a Life in Science Online

Authors: James D. Watson

Tags: #General, #Biography & Autobiography, #Personal Memoirs, #Self-Help, #Life Sciences, #Science, #Scientists, #Molecular biologists, #Biology, #Molecular Biology, #Science & Technology

For several days, I eagerly anticipated a November 1 state dinner at the White House to which I received a last-minute invitation. Though the event was intended to honor the grand duchess of Luxembourg, I was more keen to see America's royal couple in action. Only six months had passed since they had elegantly honored the nation's 1961 Nobel Prize winners, so I now thought the occasion might find me seated beside Jackie. All such thoughts, however, were abruptly interrupted by the Cuban missile crisis. JFK's speech to the nation on Monday, October 20, was not one to be listened to alone. Nervously, I went to the Doty home to watch it on their relatively big TV screen. Even before the speech was over I knew the gravity of the situation was such that a politically unnecessary state dinner was bound to be cancelled. From then on the president's attention would necessarily be focused on whether the Soviets would challenge the American blockade of Cuba, in which case the prospect of nuclear war seemed very real indeed.

Over the next several days, I had to wonder whether a month hence I would, in fact, be going to Stockholm. The Soviets might very well set up their own blockade of Berlin. Happily, less than a week passed before Nikita Khrushchev backed down. By then it was too late to reschedule the dinner for the grand duchess. The White House, however, kept me in view and invited me to a December luncheon for the president of Chile. But the thrill that came of seeing the White House envelope vanished when I opened it and saw that the date overlapped with Nobel week. I continued hoping that there might be a place for me at still another White House affair. But by the new calendar year I was no longer a celebrity of the moment.

A postcard from Berkeley brought me some unexpected happiness. It was from my former Radcliffe friend Fifi Morris, who five years before had become quite angry with me over a fondness I developed for her roommate. Equally unexpected was a letter originating in Chicago from Margot Schutt, whose acquaintance I made aboard a ship headed back to England in late August 1953. After graduating from Vassar, she had moved to Boston at the same time I came to Harvard. We had briefly dated in early 1957, until one day when she abruptly hinted that I was not a good enough reason for her to remain in Boston by announcing she would be setting off for London. Now she lived in Chicago and had read that I was scheduled soon to visit the University of Chicago.

The Chicago trip had been arranged some months before the Nobel Prize announcement. Suddenly it became a media event, with visits to my former grammar school and high school hastily arranged. Also making a return visit to Horace Mann Grammar School that day was Greta Brown, the principal when I was there between the ages of five and thirteen. Earlier she had penned me a warm letter recalling my bird-watching days and regretting that my very well-liked mother had not lived to enjoy my triumph. The school auditorium was crammed as I spoke from the stage, gazing once again upon its handsome big WPA murals. The next day, in the

Chicago Daily News

a nearly whole-page spread was headlined “The Return of a Hero” and quoted a teacher remembering me as “very short in stature but with a very eager mind.” Later at South Shore High School I spoke to an even larger audience including my former biology teacher, Dorothy Lee, who much encouraged me during my sophomore year.

At the University of Chicago, my new fame caused my scheduled lecture to be relocated to the large law school auditorium. Later I went for dinner to the Hyde Park home of a friend from my phage past, the University of Chicago biochemist Lloyd Kosloff. The next afternoon, I was at the ABC television studios for an afternoon taping of Irv Kupcinet's show. A real Chicago celebrity owing to his

Sun-Times

daily gossip column, Kup also hosted a three-hour talk show on which that day I shared billing with the authors Leo Rosten and Vance Packard.

That evening my dinner with Margot Schutt ended with a surprise twist. At a French restaurant on the North Side, we brought each other up to date on our recent pasts. She was currently working at the Art Institute, where the Sunday afternoon public lectures of my uncle Dudley Crafts Watson had been long appreciated. Though what had always most attracted me about Margot were her almost Jamesian mannerisms, I had not anticipated a Jamesian end to the evening. Over dessert she suddenly asked me if I would have actually gone through with marrying her if she had accepted my advances that spring of ‘57.1 didn't know what to say and the taxi ride back to her flat passed largely in an awkward silence.

The next day I flew on to San Francisco and went down to Stanford to talk science. Then I traveled across the bay to Berkeley, where I stayed with Don and Bonnie Glaser. Two years before, Don had won the Nobel Prize in Physics for his invention of the bubble chamber, causing them to advance their wedding date so that they could fly off together as man and wife to Sweden. In her note of congratulations, Bonnie encouraged me to set my sights on a Swedish princess, suggesting Désirée for both her poise and beauty, as well as having more to say than her two older sisters. So I told them about a telegram from my Caltech friend, the physicist Dick Feynman, wherein he proposed the same scenario with even more irony: “And there he met the beautiful princess and they lived happily ever after.” More seriously we gossiped about my Radcliffe friend Fifi, now a Berkeley graduate student. I picked her up the next evening at her flat off Channing Way, driving to Spenler's fish restaurant near the water at the foot of University Avenue. There I again saw the good-natured, intelligent personality the memory of which had led me to conclude she would be a most appropriate Stockholm consort. But still haunted by Margot's Jamesian question, I kept our dinner talk light, letting her know that my father and sister happily anticipated being with me in Stockholm. The evening ended with our deciding to see each other again during my planned February visit back to the Bay Area.

My forthcoming Nobel address soon preoccupied me at Harvard. Maurice was to give his talk on his King's College lab work confirming the double helix; Francis would focus on the genetic code; and I would talk about the involvement of RNA in protein synthesis. Happily, my Harvard science of the past five years was equal to a Nobel lecture. I gave it a dry run in late November at Rockefeller University, using the occasion to visit the BBC offices in New York to let them tape my recollections of the man Francis was before his great talents had become widely appreciated. By then I had bought the necessary white-tie outfit at the Cambridge branch of J. Press, whose first shop in New Haven had long been purveyor par excellence of preppy clothing to Yale's undergraduates. Soon after coming to Harvard, I had begun getting my suits at their Mt. Auburn Street store, finding their clothes to be among the few available that fit my still-skinny frame. Perhaps sensing my high spirits, the salesman easily persuaded me also to purchase for the august occasion a black cloth coat with a fur collar.

Early on the afternoon of December 4 my sister joined Dad and me in New York for our Scandinavian Airlines flight. Our plans were to stop over for two nights in Copenhagen to see friends Betty and I had made when we lived there in the early 1950s. But after crossing the Atlantic, the pilots discovered that Copenhagen was fogged in. So we found ourselves in Stockholm two days earlier than expected. Bypassing customs as if we were a diplomatic delegation, we were whisked by limousine to the storied Grand Hotel, built in 1874, across from the Royal Palace, onto which looked my room, among the finest in the house. I soon joined my sister and Dad for a herring-heavy smorgasbord, where we lunched with Kai Falkman, the young Swedish diplomat who would accompany us to all our Nobel week engagements. After a much-needed nap, we all supped together in the rathskeller of a restaurant in the Old Town, whose buildings date back to the fifteenth century. There Kai told us that the youngest of the four Swedish princesses, Christina, wanted to spend a year at an American university, possibly Harvard, following graduation from her Swedish high school. Conceivably she would like to talk with me during my Nobel visit. Naturally, I pledged to make myself obligingly available to explain Radcliffe's unique relation to Harvard.

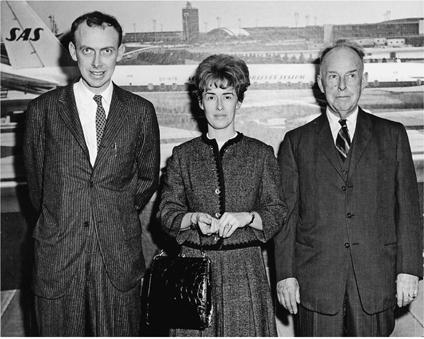

My sister, Betty, my father, and I upon our arrival in Stockholm in December 1962

Not waking until almost noon the next day, I saw my picture on the front page of Stockholm's

Svenska Dagbladet

together with a chatty article mentioning my interests in politics as well as birds. Unfortunately, the sore throat that had followed my bad cold of October soon forced me to seek medical attention. So my first view of the Karolinska Institutet complex was of its main hospital, not of its research labs. There I was examined by its leading nose and throat specialist, who saw nothing worrisome but did reveal he had been a member of the committee that had chosen me for the Nobel. In that official capacity, he greeted me when I arrived at Nobel House the next evening for the reception given by the Karolinska Institutet. This was not a formal event, and I arrived in the pinstripes that I had worn on the air journey to Sweden. The Foundation House also served as the home of Nils Stahle, its executive director, and I was pleased that his pretty, red-haired, unmarried daughter Marlin was at home for the evening, as was Helen, the very blond daughter of Sten Friberg, the rector of Karolinska.

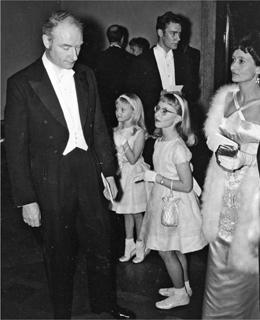

My sister, Betty, watches as Princesses Désirée, Margaretha, and Christina take their seats.

Both girls were later welcome sights at the first formal event of the week, the Nobel Foundation's reception for all the year's laureates. In the grand library of the Swedish Academy, the dominant figure was John Steinbeck, who had arrived in Sweden only that morning. Though his anticipation of the honor had been keen, he was more nervous than happy, worrying about his Nobel address the next evening. William Faulkner's address of 1950 was still remembered with reverence, and Steinbeck was feeling the pressure of expectations. That evening he and his wife went off to dinner with the Swedish literary intelligentsia while I went with my fellow laureates in science to sup at the elegant naval officers’ mess room on Stockholm Harbor at Skeppsholmen.

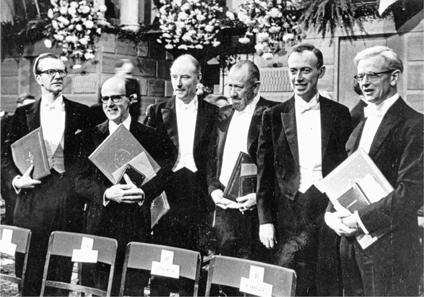

The Nobel ceremony, December 1962. From left to right: Maurice Wilkins, Max Perutz, Francis Crick, John Steinbeck, me, and John Kendrew