Avoid Boring People: Lessons From a Life in Science (12 page)

Read Avoid Boring People: Lessons From a Life in Science Online

Authors: James D. Watson

Tags: #General, #Biography & Autobiography, #Personal Memoirs, #Self-Help, #Life Sciences, #Science, #Scientists, #Molecular biologists, #Biology, #Molecular Biology, #Science & Technology

My mind turned again to potential second-generation experiments as soon as the seasickness-inducing vessel

Stockholm

docked in Copenhagen. There I found Kalckar keen that I focus instead on enzymes that make the nucleoside precursors of DNA. But after a week listening to Herman's almost indecipherable English, I saw that experiments with nucleosides would never get at the essence of DNA. I, however, could not figure out a graceful way to tell Herman that my time was better spent going back to phage experiments. Deciding to say nothing, I was soon cycling each day through the center of Copenhagen to the State Serum Institute, where Herman's friend Ole Maaloe was keen to follow up the private phage course given to him by Max at Caltech.

Long before we began producing second-generation results, Kalckar's marriage suddenly collapsed. No longer enzyme-driven, Herman was obsessing about Barbara Wright, the feminine component of our calamitous camping trip to Catalina Island the year before. Like me, she was a new postdoc in Kalckar's lab, as was Günther Stent, who'd come from Caltech the month before. Delusionally believing Barbara's Ph.D. thesis had earth-shattering implications, Herman hastily arranged an afternoon get-together at the Institute for Theoretical Physics, where Günther and I listened to her explain her experiments to Niels Bohr. Herman then proudly acted as intermediary between Barbara, his putatively visionary biologist, and Bohr, the inarguably visionary physicist. After an hour passed, Bohr politely excused himself.

By winter's end, Ole and I finished our experiments, getting the answer that the first-generation progeny transmitted DNA to their second-generation progeny no better than the parental particles. No evidence suggested the existence of two forms of DNA. Though this was not the answer we had hoped for, Max thought it sufficiently important to submit the resulting manuscript to the

Proceedings of the National Academy.

Soon Herman himself felt the need to absent himself from his lab, announcing that he and Barbara would spend April and May at the Zoological Station in Naples. Maintaining the facade that I was still his postdoc, Herman asked me whether I wanted to join him in learning more about the marine biology that Barbara had been raised on. Instantly I accepted, for I had no potentially exciting phage experiment on the horizon.

Just before I left Copenhagen, there was a small microbial genetics gathering to which came the Italian aristocrat Niccolò Visconti di Modrone, whose keen intelligence I had first witnessed the preceding August at Cold Spring Harbor. Just back in Milan from Caltech, Niccolò said I must stop off in his ancestral city to hear a performance at La Scala. Upon meeting my train from Copenhagen, he noticed that my rucksack held all my belongings, and deduced I was without a dark suit. So he arranged for us to go to the same Weber opera but on different nights. At the genetics department in the nearby small university town of Pavia, Niccolò and I bumped into Ernst Mayr, whom Niccolò also knew from Cold Spring Harbor. After we all visited the ancient Certosa di Pavia, we had supper in the large farmhouse of Nic-colò's equally tall and good-looking brother, just back from China.

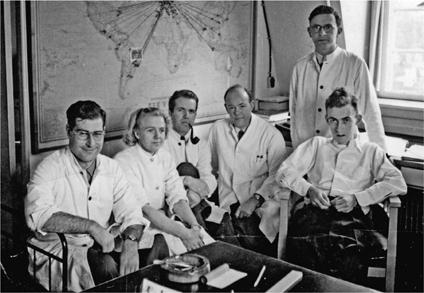

At the State Serum Institute in Copenhagen, 1951. Günther Stent is on the far left, Ole Maaloe is third from left, Niels feme is standing, and I am sitting in front of Niels.

I would have considered such acculturation alone ample justification for my spending two months in Italy, but a small, high-level meeting on macromolecular structure in the Zoological Station auditorium provided an even better excuse. Until that mid-May gathering in Naples, I had assumed no one would soon understand the detailed, three-dimensional structure of DNA at the atomic level. Since genetic information, which was encoded within DNA, varied, each different DNA molecule most likely presented a different structure to solve. But my pessimism, born of chemical naivete, lifted dramatically after a talk by the youngish King's College London physicist Maurice Wilkins. Instead of revealing disorganized DNA molecules, DNA in his X-ray diffraction pictures was yielding patterns consistent with crystalline assemblies. Later he told me that the DNA structure might not be that difficult to solve since it was a polymeric molecule made up from only four different building blocks. If he was right, the essence of the gene would emerge not from the genetic approaches of the phage group but from the methodologies of the X-ray crystallographer.

Despite my obvious excitement at his results, Maurice did not seem to judge me a useful future collaborator. So upon arriving back in Copenhagen, I wrote Salva seeking help in finding another biologically oriented crystallographic lab in which I could learn the basic methodologies of the structural chemist. Salva delivered after a meeting in Ann Arbor at which he met the Cambridge University protein crystallographer John Kendrew. Then just thirty-four, John was seeking an even younger scientist to join him. With Salva having spoken well of my abilities, he agreed to my coming aboard to learn crystallographic methodologies from him and his colleagues at the recently established Medical Research Council (MRC) Unit for the Study of Structure of Biological Systems.

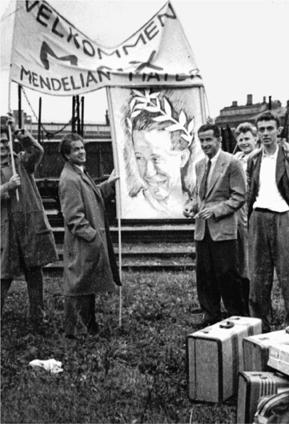

By then I was again studying the transmission of radioactive labels from parental to progeny phages, knowing that early in September Max Delbrück was coming to Copenhagen for an international poliomyelitis conference. When his ship arrived, Günther, Ole, and I went to the Copenhagen dock to greet Max with a large poster saying “Velkommen Max Mendelian Mater.” The congress itself was a routine affair except for dinner at Niels Bohr's home within the Carlsberg Brewery. Its founder had long before arranged that his opulent domicile should always be occupied by Denmark's preeminent citizen. Luckily, I was not seated near Bohr, who was likely to be expressing thoughts that no one around him, Danish or foreign, could understand.

Soon I was in England to meet John Kendrew's coworker Max Perutz, to make preparations for my coming to Cambridge in early October. Though John was still in the States, my meeting with Perutz and his boss, the Cavendish Professor of Physics, Sir Lawrence Bragg, went well and I took that night's train to Edinburgh for a two-day peek at the Scottish Highlands near Oban. In returning by train to London, I was engrossed in Evelyn Waugh's

Brideshead Revisited.

Delbrück was ending his European trip with visits to André Lwoff and Jacques Monod at the Institut Pasteur, and so from London I flew to Paris. There on a Sunday afternoon, after watching Monod nimbly scale the big boulders in the woods at nearby Fontainebleau, I said goodbye to Max as he boarded a plane at Orly Though Max was highly skeptical of my foray into a Pauling-like structural chemistry, he did not choose this occasion to say so. Instead he wished me well and I felt the creeping apprehension of knowing that I would no longer be part of the world in which grace and the fall from it could be comfortably predicted by asking, “What will Max say?” Soon I would be somewhere he did not matter.

Max Delbrück arrives in Copenhagen, September 1951. From left: Günther Stent, Ole Maaloe, Carsten Bresch, and Jim Watson

Remembered Lessons

1. Have a big objective that makes you feel special

No one within the phage group of 1950 would have denied our air of self-importance or our sense of being a happy few. The disciples of George Beadle and Ed Tatum working with

Neurospora

on gene-enzyme connections never came together with such esprit de corps. Max Delbrück's personality was a big factor. His reverence for deep truths and commitment to sharing them unselfishly was saint-like. But these virtues attend many uninspired minds as well and were never the key to the fervor of his acolytes. Instead it was his great commission that we go to the heart of the gene, in search of its genetic and molecular essences. To obssess over less fundamental goals made no sense to Max. Phages, being virtually naked genes that yielded answers after only a night's sleep, had to be the best biological tools for moving forward fast. Legions of graduate students across biology were pursuing things worth knowing but perhaps not worth devoting one's life to. The quest for such an unrivaled prize of indisputable significance fired in our imaginations a devotion such as religion fires in others', but without the irrationality.

2. Sit in the front row when a seminar's title intrigues you

By far the best way to profit from seminars that interest you is to sit in the front row. Not being bored, you do not risk the embarrassment of falling asleep in front of everybody's eyes. If you cannot follow the speaker's train of thought from where you are, you are in a good place to interrupt. Chances are you are not alone in being lost and most everyone in the audience will silently applaud. Your prodding may in fact reveal whether the speaker indeed has a take-home message or has simply deluded himself into believing he does. Waiting until a seminar is over to ask questions is pathologically polite. You will probably forget where you got lost and start questioning results you actually understood.

Now, if you have suspicions that a seminar will bore you but are not sure enough to risk skipping it, sit in the back row. There a dull, glazed expression will not be conspicuous, and if you walk out, your departure may be thought temporary and compelled by the call of nature. Szilard did not follow this advice, habitually sitting in a front row and getting up abruptly in the middle of talks when he'd had too much of too little. Those outside his close circle of friends were relieved when his inherent restlessness made him move on to a potentially more exciting domicile.

3. Irreproducible results can be blessings in disguise

A desired result in science is gratifying, but there is no contentment until you have repeated your experiments several times and got the same answer. AI Hershey called such moments of satisfaction “Her-shey heaven.” Just the opposite feeling of maddening inferno comes from irreproducible results. Albert Keiner and Renato Dulbecco felt it before they found that visible light can reverse much UV damage. Del-briick, struck by how long this phenomenon remained undiscovered, put it down to fastidiousness. He described what he called “the principle of limited sloppiness.” If you are too sloppy, of course you never get reproducible results. But if you are just a little sloppy, you have a good chance of introducing an unsuspected variable and possibly nailing down an important new phenomenon. In contrast, always doing an experiment in precisely the same way limits you to exploring conditions that you already suspect might influence your experimental results. Before the Kelner-Dulbecco observations, no one had cause to suspect that under any conditions visible light could reverse the effects of UV irradiation. Great inspirations are often accidents.

4. Always have an audience for your experiments

Before starting an experiment, be sure others are interested in the premise. Mindless minor variations on prior good science will generate yawns in the world beyond your lab. Though such almost repetitive motions are good ways for students to learn lab techniques, they should be seen as exercises and not as real science, with their results publishable only in journals that hotshot scientists never read. Now, trying to break new ground may lead to consequences that seem worse than yawns, and you must be prepared for most of your peers to think you are out of your mind. If, however, you cannot think of at least one and preferably several bright individuals who can take appreciative notice of what you are doing, your tenacity may very well indicate that you are either stupid or crazy.

5. Avoid boring people

Social gatherings of even successful academics are no different from gatherings of any professional cohort. The truly interesting are inevitably a small subset of any group. Don't be surprised when arriving at some senior colleague's house for dinner if you feel an unexplainable desire to leave when you learn whom you're seated next to. Routinely reading the

New York Times

at breakfast will expose you to many more facts and ideas than you are ever likely to acquire during evenings with individuals who in most instances haven't had to think differently since getting tenure. Unless you have reason to anticipate a very good meal or the presence of a fetching face, take care not to accept outright any invitations to senior faculty's homes. Leave open the possibility that a sixteen-hour experiment might keep you from coming. If you later find out that someone you want to meet will be there, make known your sudden availability and come gallantly with a small box of chocolates to enjoy with the coffee.