All Hell Let Loose (66 page)

Read All Hell Let Loose Online

Authors: Max Hastings

The man told the correspondent, ‘We’ve seen no bread for three months. We eat grass.’ Then he asked fearfully, ‘Will the Germans come back?’ Brontman gave them a kilo of bread, which they gazed on as a precious delicacy. Another family, whom Brontman invited to share a brew of tea, refused the offer; they had lost the habit of such luxuries, they said dully. Yet these people lived in what was once one of Russia’s greatest agricultural regions. Censors intercepted a letter from a mother named Marukova in liberated Oryol, to her son in the Red Army: ‘There is no bread, to say nothing of potatoes. We are eating grass and my legs refuse to walk.’ Another mother named Galitsina in the same district wrote likewise: ‘When I get up in the morning I don’t know what to do, what to cook. There is no milk, bread or salt, and no help from anyone.’

The Germans staged their initial withdrawal from Kursk in good order, but no one on either side doubted that they had suffered a calamitous defeat, sustaining half a million casualties in fifty days of fighting. Stalin, triumphant, displayed his revived self-confidence by issuing new orders to rein in Zhukov and Vasilevsky. After the triumph of Stalingrad, five subsequent attempts to achieve matching envelopments of German armies had failed. In future, he decreed, the Red Army would launch frontal assaults rather than encirclements. By the end of August, eight Soviet

fronts

were conducting nineteen parallel offensives towards the Dnieper along a line of 660 miles from Nevel to Taganrog. On 8 September, Hitler authorised a withdrawal behind the river, where the Russians were improvising crossings with any means to hand. They staged one of their few massed air drops of the war on the west bank, landing 4,575 paratroopers, of whom half survived.

The Russian armies drove forward in the same desperate fashion in which they had retreated in the previous year, numbed by daily horrors. Victory at Kursk meant little to a soldier such as Private Ivanov of 70th Army, who wrote despairingly to his family in Irkutsk: ‘Death, and only death awaits me. Death is everywhere here. I shall never see you again because death, terrible, ruthless and merciless is going to cut short my young life. Where shall I find strength and courage to live through all this? We are all terribly dirty, with long hair and beards, in rags. Farewell for ever.’ Private Samokhvalov was in equally wretched condition: ‘Papa and Mama, I will describe to you my situation, which is bad. I am concussed. Very many of my unit have been killed – the senior lieutenant, the regimental commander, most of my comrades; now it must be my turn. Mama, I have not known such fear in all my eighteen years. Mama, please pray to God that I live. Mama, I read your prayer … I must admit frankly that at home I did not believe in God, but now I think of him forty times a day. I don’t know where to hide my head as I write this. Papa and Mama, farewell, I will never see you again, farewell, farewell, farewell.’

Pavel Kovalenko wrote on 9 October: ‘We passed through the area where the 15th Regiment had been trapped. There are corpses everywhere and smashed carts. Many bodies have their eyes poked out … Are the Germans human? I cannot come to terms with such things. People come – and they go. Senior Lieutenant Puchkov got killed. I am sorry about the lad. Last night a cavalryman trod on a mine. Both soldier and horse were blown to pieces. When night fell I sat shivering by the fire, my teeth chattering with wet and cold.’

Next day, his unit trudged into a Belorussian settlement named Yanovichl. ‘What’s left of it? Just ruins, ashes and charred remains. The only living souls are two cats, their fur scorched. I stroked one of them and gave it some potatoes. It purred at me … Everywhere there are lots of unharvested potatoes, beetroot and cabbage. Before driving away the population, the Germans suggested that they bury their belongings. Now, these pitiful relics of domestic felicity lie scattered in gardens. The Germans have taken everything useful. One house has survived out of three hundred, the rest succumbed to flame. An old woman sits grieving. Her eyes are lifeless, gazing frozen into the far distance. She has nothing left, and icy winter is almost upon us.’

Day after day as the Red Army advanced, such scenes were repeated. ‘I was shaken by the ferocity of the tank battles,’ said Ivan Melnikov. ‘What did people feel in those steel boxes under fire? I once saw ten or eleven burned-out T-34s in one place, a ghastly sight. Almost all the bodies lying nearby were badly burnt, while those who had stayed in their tanks had turned into firebrands, lumps of charcoal.’ One night a reconnaissance section from his unit was caught in the open under German flares; four of its six men were killed, and next day the Germans amused themselves by using the bodies for target practice. ‘[They] were a terrible sight by evening: shapeless, torn by bullets, their faces blown off, arms severed.’

Commanders drove units so far and fast that horses pulling baggage carts became too weary to eat their hay. Many animals lay dead by the roadside amid rows of hastily dug German graves, skulls, half-decayed corpses, abandoned sledges, burnt-out vehicles. ‘We march in the footsteps of war,’ mused Kovalenko. ‘Chaos is majestic in its way. I contemplate this vista of destruction and death with pain and helplessness in my soul.’

As snow once more closed down the battlefield in the last months of 1943, the Russians held a large bridgehead beyond the Dnieper around Kiev, and another at Cherkassy. The Germans lost Smolensk on 25 September, and retained only an isolated foothold in the Crimea. On 6 November, the Russians took Kiev. Vasily Grossman described an encounter with infantrymen near the shattered city that day:

The deputy battalion commander, Lieutenant Surkov, has come to the command post. He hasn’t slept for six nights. His face is heavily bearded. One can see no tiredness in him, because he is still seized by the terrible excitement of fighting. In half an hour, perhaps, he will sink into sleep with a field bag under his head, and then it would be useless to try to wake him. But now his eyes are shining, and his voice sounds harsh and excited. This man, a history teacher before the war, seems to be carrying with him the glow of the Dnieper battle. He tells me about German counter-attacks, about our attacks, about the runner whom he had to dig out of a trench three times, and who comes from the same area as he, and was once his pupil – Surkov had taught him history. Now, they are both participating in events about which history teachers will be telling their pupils a hundred years from now.

Over half the Soviet territory lost to Hitler since 1941 had been regained. By the end of 1943, the Soviet Union had suffered 77 per cent of its total casualties in the entire conflict – something approaching twenty million dead. ‘The enemy’s front is broken!’ wrote Kovalenko triumphantly on 20 September. ‘We are advancing. We are moving slowly, groping our way. Everywhere are traps, minefields. We’ve advanced 14 km during the day. There was a “little misunderstanding” at 14.10. A group of our aircraft got confused and strafed our column. It was dismaying to see them firing at their own people. Men were wounded and killed. It is so bad.’ He added on 3 October:

Our organisation both on the march and in action leaves much to be desired. In particular, infantry–artillery coordination is poor: the gunners fire at random. [We have suffered] colossal casualties. There are only sixty men left in each of our regiment’s battalions. What are we supposed to attack with? The Germans are resisting ferociously. Vlasov soldiers [Cossack renegades] are fighting alongside them. Dogmeat. Two have been captured, teenagers, born 1925. [We should] not mess about, but shoot the sons-of-bitches. [Three days later, he wrote:] We are advancing again, but with scant success – just a little progress here and there. We have few infantry, and are desperately short of shells. The Germans burn every village. Our reconnaissance units operating in their rear areas have led a lot of civilians out of the forest where they had been hiding. We seem stuck in the swamps. When shall we get out of here? Rain, mud.

Captain Nikolai Belov’s unit was in the same plight: ‘The weather and mud are dreadful. We face a winter amid forests and swamps. Today, we set off at 1000 and advanced about six kilometres in twenty-four hours. There is no ammunition. Rations are short because supplies have fallen behind. Many men are without boots.’

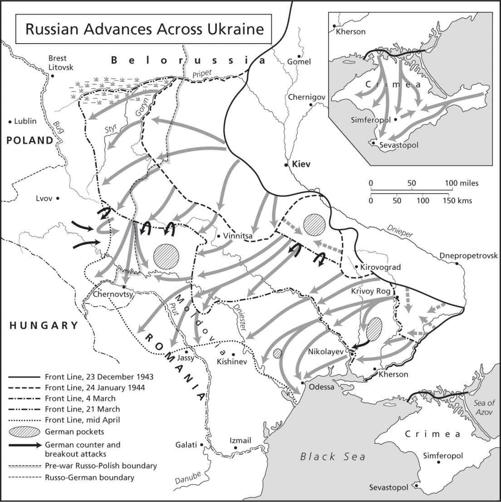

Russian Advances Across Ukraine

Few Russian soldiers saw much cause for rejoicing, because they knew how long was still the road to Berlin. An elderly officer named Ignatov wrote to his wife, complaining of the poor organisation of the army: ‘The soldiers with whom I fought in 1917–18 were much better disciplined. We receive completely untrained replacements. As a veteran of the old army, I know what a Russian soldier should be like; whenever I try to bring these men up to the mark they moan and complain of my harshness. We were sent into battle without spades, though they had promised them to us. We are sick of promises we no longer believe.’ An NCO in Vladimir Pershanin’s unit was sent with his lieutenant to recover the identity capsules of eight of his men killed when the officer lost his way, and led them into the path of a German machine-gun: ‘“You shit!” said the sergeant, not addressing the lieutenant directly, but spitting towards him. “Eight lives for fuck-all!”’

The German predicament, however, was vastly worse. ‘This morning the combat strength of 39th Infantry Division was down to six officers and roughly three hundred men,’ wrote one commander in a 2 September morale report. ‘Apart from their dwindling strength, the men’s state of fatigue gives rise to great anxiety … Such a state of apathy has arisen among the troops that draconian measures do not produce the desired results, but only the good example of officers and “kindly persuasion”.’ Ghastly scenes took place during the flight to the Dnieper, as discipline broke down in a fashion unprecedented for the Wehrmacht. ‘Frantic men were abandoning everything on the bank and plunging into the water to try to swim to the opposite shore,’ wrote a soldier. ‘Thousands of voices were shouting towards the grey water and the opposite bank … The officers, who had managed to keep some self-control, organised a few more or less conscious men, like shepherds trying to control a herd of crazed sheep … We heard the sounds of gunfire and explosions punctuated by blood-curdling screams.’ Many men eventually crossed on improvised rafts.

Once more, the German army regrouped; once more it prepared to hold a line with dogged determination. Many more battles lay ahead. Panzer officer Tassilo von Bogenhardt mused on the paradox that almost all his men were by now resigned to death, yet their morale remained high: ‘Each German soldier considered himself superior to any single Russian, even though their numbers were so overpowering. The slow, orderly retreat did not depress us too much. We felt we were holding our own.’ But soon afterwards he was badly wounded and captured; he somehow survived the ensuing three years as a prisoner. 1943 on the Eastern Front had brought upon the invaders of Russia irredeemable catastrophe, and to Stalin’s armies the assurance of looming triumph.

1

WHOSE LIBERTY?

Winston Churchill stretched an important point by telling the House of Commons on 8 December 1941: ‘We have at least four-fifths of the population of the globe on our side.’ It would have been more accurate to assert that the Allies had four-fifths of the world’s inhabitants under their control, or recoiling from Axis occupation. Propaganda promoted an assumption of common purpose in the ‘free’ nations – among which it was necessary to grant nominal inclusion to Stalin’s people – in defeating the totalitarian powers. Yet in almost every country there were nuances of attitude, and in some places stark divergences of loyalty.

South America was the continent least affected by the struggle, though Brazil joined the Allied cause in August 1942 and sent 25,000 of its soldiers to participate – albeit almost invisibly – in the Italian campaign. Most of the nations that escaped involvement were protected by geographical remoteness. Turkey was the most significant state to sustain neutrality, having learned its lesson from rash involvement in World War I on the side of the Central Powers. In Europe, only Ireland, Spain, Portugal, Sweden and Switzerland were fortunate enough to have their sovereignty respected by the belligerents, most for pragmatic reasons. Ireland had gained self-governing dominion status only in 1922, although until 1938 Britain retained control of four strategically important ‘treaty ports’ on its coastline. In 1939–40, as the former mother nation began its struggle for survival against the U-boat, Winston Churchill was tempted by the notion of reasserting by force his country’s claims upon these naval and air bases. He was dissuaded only by fear of the impact on opinion in the United States, where there was a strong Irish lobby.

The Atlantic ‘air gap’ was significantly widened, and many lives and much tonnage lost, in consequence of the fanatical loathing of Irish prime minister Éamon de Valera for his British neighbours. The crews of almost every warship and merchantman that sailed past the Irish coastline in the war years felt a surge of bitterness towards the country which relied on Britain for most of its vital commodities and all its fuel, but would not lift a finger to help in its hour of need. ‘The cost in men and ships … ran up a score which Irish eyes a-smiling on the day of Allied victory were not going to cancel,’ wrote corvette officer Nicholas Monsarrat. ‘In the list of people you were prepared to like when the war was over, the man who stood by and watched while you were getting your throat cut could not figure very high.’ Yet because of Ireland’s divided sovereignty and loyalties, even Northern Ireland, still a part of the United Kingdom, never dared to introduce conscription for military service. The perverse outcome was that more Catholic southern Irishmen than Protestant Northerners – who loudly asserted their commitment to the crown – served in Britain’s wartime armed forces, though the services of most southerners were purchased by economic necessity rather than seduced by ideological enthusiasm for the Allied cause.

The Swedes asserted their status with a rigour promoted by proximity to Germany and thus vulnerability to its ill-will: they arrested and imprisoned scores of Allied intelligence agents and informants. Only in 1944–45, when the outcome of the war was no longer in doubt, did the Stockholm government become more responsive to diplomatic pressure from London and Washington, and less zealous in locking up Allied sympathisers.

Switzerland was a hub of Allied intelligence operations, though the Swiss authorities foreclosed all covert activities they discovered. They also denied sanctuary to Jews fleeing the Nazis, and profited enormously from pocketing funds deposited in Swiss banks by both prominent Nazis and their Jewish victims, which later went unclaimed because the owners perished. The daughter of a rich French Holocaust victim, Estelle Sapir, said later: ‘My father was able to protect his money from the Nazis, but not from the Swiss.’ Switzerland provided important technological and industrial support to the Axis war effort, in 1941 increasing its exports to Germany of chemicals by 250 per cent, metals by 500 per cent. The country became a major receiver of stolen goods from the Nazi pillage of Europe, and banked what the OSS, Washington’s covert operations organisation, categorised as ‘gigantic sums’ of fugitive funds. The Swiss unblinkingly paid to the Nazis the proceeds of life insurance policies held by German Jews, and the Bern government dismissed post-war recriminations about such action as ‘irrelevant under Swiss law’. Only a fraction of Switzerland’s enormous profits from wartime misappropriations were ever acknowledged, and an even smaller portion paid out to Jewish victims and their families. The war proved good for business in the ice-hearted cantons.

Among the belligerents, unsurprisingly the more distant was a given Allied country from the consequences of Axis aggression, the less ill-will its people displayed towards the enemy. For instance, an Office of War Information poll in mid-1942 found that one-third of Americans expressed willingness to make a separate peace with Germany. A January 1944 opinion survey showed that while 45 per cent of British people professed to ‘hate’ the Germans, only 27 per cent of Canadians did so.

For most people in Europe and Asia, the conflict was a pervasive reality. Families in the Asian republics of the Soviet Union, among the remotest places on earth, found their menfolk conscripted for the Red Army, prison camps established within sight of their villages, food chronically short. A Japanese air raid on the north Australian port of Darwin on 19 February 1942 killed 297 people, most of them service personnel on ships in the harbour. Though the attack was never repeated, and Australia was thereafter troubled by only sporadic small-scale Japanese naval intrusions, the country’s sense of invulnerability was shattered. Tribesmen on Pacific islands and in Asian jungles were enlisted to serve one army or another, though often oblivious of what their sponsors were fighting about. Even in parts of Russia, the same ignorance obtained: beside the Pechora river inside the Arctic Circle a gulag camp boss described how local villagers ‘had a very vague understanding about what was going on in the world. They did not even know very much about the Soviet war with Germany.’

Large majorities in the belligerent nations – with the notable exception of Italy – supported the causes championed by their respective governments, at least unless or until they started losing. But minorities dissented, and thousands were imprisoned in consequence, some of them by the democracies. So too were people whose allegiance was deemed suspect, sometimes grossly unjustly: Britain in 1939 detained all its German residents, including Jewish fugitives from Hitler. The historian G.M. Trevelyan was among prominent figures who denounced indiscriminate internment, saying that the government failed to recognise ‘the great harm that is being done to our cause – essentially a moral cause … by the continued imprisonment of political refugees’. America made the same mistake in the hysteria following Pearl Harbor, by interning its Nisei Japanese. The governor of Idaho, supporting drastic measures, said: ‘The Japs live like rats, breed like rats and act like rats. We don’t want them.’

At the outbreak of war, the United States was by no means a homogeneous society. American Jews, for instance, suffered suspicion, if not hostility, from their own countrymen, exemplified by their exclusion from country clubs and other elite social institutions. A wartime survey showed that Jews were mistrusted more than any other identified ethnic group except Italians; a poll in December 1944 showed that while most Americans accepted that Hitler had killed some Jews, they disbelieved reports that he was slaughtering them in millions.

Black Americans had cause to regard the ‘crusade for freedom’ with scepticism, for much of their country was racially segregated, as were the armed forces. At army recruit John Capano’s training camp in South Carolina, there was a sign outside a local restaurant: ‘Niggers and Yanks not welcome’. He said, ‘It was a very white troop, which fought running battles with the blacks in the motor pool.’ 1940 witnessed six recorded lynchings of black Americans in the South, four of them in Georgia, and many more floggings, three of them fatal. Virginia matrons delivered a formal protest about Eleanor Roosevelt’s presence at a mixed dance in Washington: ‘The danger,’ they wrote to the president, ‘lies not in the degeneration of the girls who participated in this dance, for they were … already of the lowest type of female, but in the fact that Mrs Roosevelt lent her presence and dignity to this humiliating affair; that the wife of the President of the United States sanctioned a dance including … both races and that her lead might be followed by unthinking whites.’

The 1942 influx of large numbers of black workers to join the labour force in Detroit provoked vociferous white anger, which in June erupted into serious rioting. The following year witnessed further racial disturbances, in Detroit against blacks and in Los Angeles against Mexicans. The president adopted a notably muted attitude to the Detroit clash, and indeed until his death remained circumspect about racial issues. The proportion of black workers in war industries rose from 2 per cent in 1942 to 8 per cent in 1945, but they remained under-represented. America’s armed forces enlisted substantial numbers of African-Americans, but entrusted only a small minority with combat roles, and maintained a large measure of segregation; the American Red Cross distinguished between ‘colored’ and ‘white’ blood supplies. Cynics demanded to be told the difference between park benches marked ‘

Juden

’ in Nazi Germany, and those labelled ‘Colored’ in Tallahassee, Florida.

At the outbreak of war even many white Americans, immigrants or children of immigrants, defined themselves in terms of the old-world national group to which they belonged, notably including almost five million Italian-Americans: until December 1941, their community newspapers hailed Mussolini as a giant. One published letter-writer applauded the German invasion of Poland, and predicted that ‘As the Roman legions did under Caesar, the New Italy will go forth and conquer.’ Even when their country declared war on Mussolini, many Italian-Americans hoped for a US victory that somehow avoided imposing an Italian defeat.

By 1945, however, an immense change had taken place. The shared experience of conflict, and especially of military service, accelerated a remarkable integration of America’s national groupings. Anthony Carullo, for instance, had emigrated to the US from southern Italy with his family in 1938. When he joined the army and served in Europe, he had to address letters home to his sisters, because his mother understood no English. But when he was asked, ‘If we send you to Italy, are you willing to fight Italians?’ the twenty-one-year-old replied doughtily, ‘I’m an American citizen. I’ll fight anybody.’ German-born Sergeant Henry Kissinger afterwards asserted that it was the war that made him a real American. Between 1942 and 1945, millions of his compatriots of recent immigrant stock discovered for the first time a shared nationalism.

Much more complex and brutal issues of loyalty confronted societies occupied by the Axis, or subject to colonial rule by the European powers. In some countries, to this day it remains a matter of dispute whether those who chose to serve the Germans or Japanese, or to resist the Allies, were guilty of betrayal, or merely adopted a different view of patriotism. Many Europeans served in national security forces which opposed Allied interests and promoted those of the Germans: French gendarmes consigned Jews to death camps. Despite the legend of Dutch sympathy promoted by Anne Frank’s diary, Holland’s policemen proved more ruthless than their French counterparts, dispatching a higher proportion of their country’s Jews to deportation and death.

France was riven by internal dissensions. Especially in the early years of occupation, there was widespread support for the Vichy government, and thus for collaboration with Germany. A German officer working with the Armistice Commission in 1940–41, Tassilo von Bogenhardt, asserted that he found his French counterparts ‘very interesting to talk to … I suspected that the fortitude of the British in the face of our bombing rather annoyed them … [They] admired and respected Marshal Pétain as much as they detested the communists and

Front Populaire

.’ Some 25,000 Frenchmen served as volunteers in the SS Westland Division. Though the colonial authorities in a handful of France’s African possessions ‘rallied’ to de Gaulle in London, most did not. Even after the US entered the war, French soldiers, sailors and airmen continued to resist the Allies. In May 1942, when the British invaded Vichy Madagascar to pre-empt a possible Japanese descent on the strategic island, there was protracted fighting. Madagascar is larger than France – a thousand miles long. Its governor-general signalled to Vichy: ‘Our available troops are preparing to resist every enemy advance with the same spirit which inspired our soldiers at Diego Suarez, at Jajunga, at Tananarive [the sites of earlier encounters between Vichy forces and the Allies] … where each time the defence became a page of heroism written by “

La France

”.’

Clashes at sea made it necessary for the Royal Navy to sink a French frigate and three submarines; in the Madagascar shore campaign, 171 of the defenders were killed and 343 wounded, while the British lost 105 killed and 283 wounded. When the governor ordered the submarine

Glorieux

to escape to Vichy Dakar, its captain expressed frustration at being denied an opportunity to attack the British fleet: ‘All on board felt the keen disappointment I did myself at sighting the best target a submarine could ever be given without also having a chance of attacking it.’ The defenders of Madagascar finally surrendered only on 5 November 1942. Once again, few prisoners chose to join de Gaulle. Everywhere Vichy held sway, the French treated captured Allied servicemen and civilian internees with callousness, and sometimes brutality. ‘The French were rotten,’ said Mrs Ena Stoneman, a survivor from the sunken liner

Laconia

held in French Morocco. ‘We ended up thinking of them as our enemies and not the Germans. They treated us like animals most of the time.’ Even in November 1942, when it was becoming plain that the Allies would win the war, the resistance offered by French troops shocked Americans landing in North Africa.