A Writer's World (51 page)

Read A Writer's World Online

Authors: Jan Morris

Few cities on earth, in fact, now feel more dismissive of power for power’s sake than Berlin, 1989; all the monuments of Establishment, whether curly-wigged Junker Baroque, Nazi Neo-Classical, steel-and-concrete Stalinist Dogmatic or Capitalist Junk Pile, look a little ridiculous.

*

Fun,

gemütlichkeit

, malignity, dominance – some of these emblematic qualities I found alive, some mercifully buried. At the end of my stay I searched for another that might represent not my responses to Berlin’s

past and present, but my intuitions about its future. I spread out before me – in the Café Einstein, pre-eminently the writer’s café of contemporary Berlin, where you can write novels until closing time over a single cup of coffee – my 1913 Baedeker’s plan of Berlin, and looked for omens in it.

It showed a city of great magnificence, compact and ordered around the ceremonial focus of the Brandenburg Gate, with parklands and residential districts to the west of it, the offices of state and finance to the east. Where now almost everything seems random, ad hoc, or in transition, Baedeker’s 1913 plan shows nothing but rational and permanent arrangement. Modern Berlin has no real centre or balance, devastated as it has been by war and fractured by that vile Wall, but the old Berlin was, in its heavy and self-conscious way, almost a model capital.

It is fashionable just now to imagine it as an imperial capital again – as the future capital of Europe, in fact, at the place where the western half of the continent meets the east. In some ways indeed it feels like an international metropolis already, frequented as it is by Westerners of every nationality, and by Turks, Romanians, Poles, Arabs, Africans and gypsies; road signs direct one to Prague and to Warsaw, and at the Zoo railway station you may meet the tired eyes of travellers, peering out of their sleeper windows, who have come direct from Moscow and are going straight on to Paris.

Physically, no doubt, Berlin can be restored to true unity. Already its wonderful profusion of parks, gardens, forests and avenues, lovingly planted and replanted through peace and war, give it a certain sense of organic wholeness. When the wasteland of the Wall is filled in with new building, when the communist pomposities of Karl-Marx Allee and Alexanderplatz have been upstaged by the cheerful detritus of free enterprise, we may see the old municipal logic re-emerging too. The focus of life will return to the old imperial quarter, and the Brandenburg Gate will once more mark the transition between public and private purpose.

But metaphysically, my ancient Baedeker suggests, it will be a different matter. The lost Berlin of its plan was built upon victory – the victory over France, in 1871, which led to the unification of Germany and made this the proudest and most militaristic capital on earth. Everything about it spoke of triumph, Empire, and further victories to come. In today’s Berlin the very idea of victory is anomalous, and triumph no longer seems a civic vocation. The world at large may still, at the back of its mind, dread the prospect of German re-unification and the revival of German power, but in my judgement at least, Berlin is no longer a place

to be afraid of. I strongly suspect that half a century from now, when this city has finally recovered its united self, it will turn out to be something much less fateful than Europe’s capital. It will be a terrific city, beyond all doubt – a city of marvellous orchestras, famous theatres, of scholarship, of research, of all the pleasurable arts – but not, instinct and Baedeker together tell me, the political and economic apex of a continent.

If I had to choose a single abstraction to suggest its future, I thought to myself as I ordered a second coffee after all, it would be something fond and unambitious: relief, perhaps, in this city of interesting times, that the worst is surely over.

Please

God

.

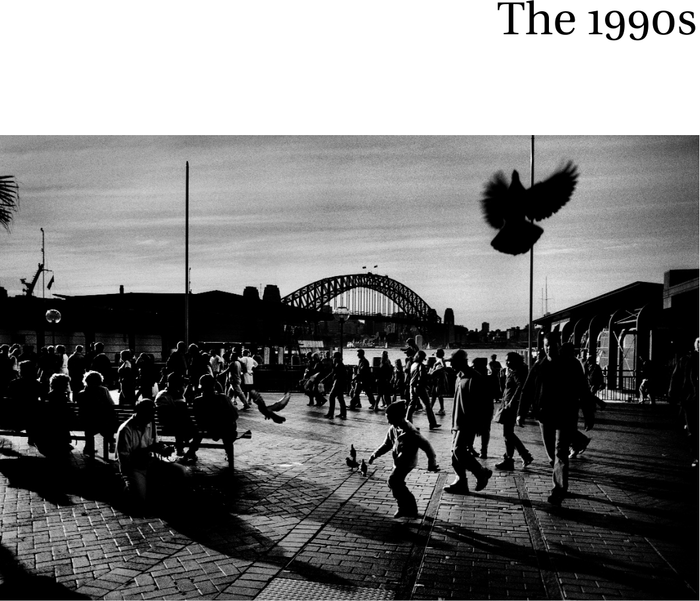

The last decade of the century seemed to me an

indeterminate decade, when nothing was conclusive.

There was no world war, but no world reconciliation

either, although an abstraction called ‘the international

community’ was much touted. Half the world got

richer, but half got poorer too. The Americans

continued their apparently inexorable march towards

domination of all the continents, fighting a war against

Iraq along the way. The communist empire finally

disintegrated, a denouement defined by Boris Yeltsin,

who presided over it, as ‘the end of the twentieth

century’, but its successor the Russian Federation

floundered in corruption and disillusionment. The

progress of Europe towards unity was mocked by the

terrible War of the Yugoslav Secession. Fundamental

brands of Islam became more ominously powerful.

It could have been worse, but it could have been

better. For me personally it was a European decade,

with intermittent forays elsewhere, and I spent much

of it gathering material for a book called

Fifty Years of Europe.

I had come to agree with Lord Tennyson’s

dictum ‘better 50 years of Europe than a cycle of

Cathay’.

Europe was in a state of flux, as the former states of the Soviet empire tentatively moved into independence, and the old democracies tried to reconcile

their disparate identities with the idea of a continental whole. Contemplating

its continuing uncertainties, and at the same time feeling footloose and

escapist, one day I decided to jump in my car and visit three of those classically

consistent parts of the continent, its famous wine-lands. This slight essay

originally ended with the exclamation ‘O, the writer’s life for me!’, but it

was really a light-hearted prologue to more serious explorations of Europe

in the 1990s

.

First I went to Haro, in Spain. I bought a bottle of a 1990 Reserva, from the Abeica bodega in the nearby village of Albeca, which was recommended to me as an exceptional example of modern Rioja, and I drank it at a table outside the Café Madrid, in the main square of the town, with a large plate of miscellaneous tapas.

Haro stands in the purest Spanish countryside, bare mountains, vine-sprinkled hillsides, castles, village churches like cathedrals, hilltop hermitages, cuckoos and crickets and solitary elderly men hoeing fields. The pilgrim route to Santiago passes near by, and nobody could ask much more of Spanishness than the Plaza de la Paz before me, which is built on a gentle slope around a florid bandstand, and has all the requisite lamp-posts, pigeons, clocks, cobbles, arcades, benches with old men asleep on them and mostly inoperative fountains. On a rooftop above my head a pair of storks is nesting.

Everyone seems to know everyone else in the Plaza de la Paz. Everyone knows the two ancient ladies who walk up and down, up and down past the café tables beneath a shared white parasol. Everyone greets the

extremely genteel seller of lottery tickets, and time and again the cry of

Hombre!

rings across the square as stocky

Jarreños

(jug-makers, as they call citizens of Haro) greet one another around the bandstand. Every passer-by peers into the convivial interior of the Café Madrid to see what friends are propping up the bar, and a few look at me curiously as I pour more wine from the bottle I have put under the table to keep it out of the sun.

I must not idealize this scene. A group of suaver Spaniards (from Burgos, they tell me) has just settled at a pair of tables on the pavement, very gold-bangled and silk-scarved and sunglassed, and a terrific pair of thugs whom I take to be Basque terrorists has just swaggered by with an alarming dog. There are a few weirdos about, bikers in leather jackets, babies in ostentatious prams. But in general the citizens do seem people without pose or affectation, a rough but serene kind of people, from a rough but generally serene place.

And the wine? Give me a moment, while I swallow this prawn and think about it. Mmm. More serenity than roughness, I think. It is example number 1,301 of a remarkable vintage of 8,400 bottles that won important prizes in Bordeaux last year, but it is loyal Rioja all the same, well-oaked, honest, strong, straight, an organic-tasting wine; and as is only proper in the new Spain – in the new Europe – its wine-maker was a woman.

*

Next to constancy of a very different kind – to the Côte de Beaune in Burgundy, France, where the Mercs and Jaguars from Switzerland cruise around looking for rich luncheons and crates of the most expensive white wine in the world.

This is a long way from the storks and homely boulevardiers of Haro. Here, one after another, the wine villages succeed each other in well-heeled complacency, like clichés: their narrow streets are spotless, their charming courtyarded villas all look as though they were steam-cleaned last week. They seem to be mostly deserted, except for meandering gourmands and the odd viniculturist stepping in or out of his Range Rover, but on every other corner a discreetly sculpted sign announces an opportunity of

dégustation

.

Being a crude islander myself, and an iconoclast at that, I decided to cock a snook here. I bought, for the first and probably the last time in my life a Grand Cru Montrachet – Marquis de Laguiche, vintage 1993. I got a kindly waitress in a café to uncork it for me, and picked up a hefty ham and cheese baguette to eat with it. ‘Kindly direct me,’ I said to a viniculturist who happened to arrive at that moment in his Range Rover, ‘to the exact patch of soil that has produced this bottle of wine.’

He raised his eyebrows slightly when he saw its label and the napkin-wrapped sandwich in my hand. It was not much of a day for a picnic, he said, but perhaps the wine would help – and with a wonderfully subtle suggestion of disapproval he pointed the way to Le Montrachet. ‘

Bon

appétit

,’ he brought himself to say, for your Burgundy viniculturist is nothing if not charming, and so a few minutes later I found myself sitting on the low stone wall that bounds the celebrated vineyard of Le Montrachet. It might have been made for picnickers. I could reach out and touch the vines, and slowly across the little road in front of me a large grey snail crawled towards the scarcely less illustrious vineyard on the other side.

There I sat and ate my baguette and drank, out of a plastic mug, the most famous dry white on earth. It was very peaceful, rather like picnicking in an extremely up-market cemetery. Not a bird twitched or a lizard flickered. Once or twice people in cars, on the little vineyard road, slowed down to take a look at me, swinging my legs there on the wall, and responded with wary smiles when I raised my mug to them. All around the vineyards extended symmetrically, neat as could be, perfect in their regularity, part of the very contours of the land, as though no human hand had ever tilled or planted them.

The wine was divine, of course. It seemed to me the essence of everything Burgundian: accomplished, fastidious, exquisitely polite, perhaps a bit Range Rovery, a little lofty in the aftertaste. But then, wouldn’t you be snooty, to find yourself drunk from a plastic mug with a ham sandwich, there in the very vineyard that had made your name revered among connoisseurs for 400 years?

*

Four hundred years? That’s nothing. My last vineyard was in the Rheingau, the greatest of the German wine-growing areas, and had been in the hands of the same patrician family since the fourteenth century. And the Rhine wine I drank, a 1993 Auslese, was from Schloss Johannisberg, which was granted to Prince Metternich by the Hapsburg emperor after the Congress of Vienna, and is still partly the property of his descendants.

If gentlemanly elegance is the hallmark of Burgundy, power seems to impregnate the soil of the Rheingau: constant, immutable power, impervious to history, sometimes latent, sometimes brazen. I stayed at the spa of Bad Kreuznach, on the west side of the river, which is where the spike-helmeted German General Staff had its headquarters in 1917, and where, thirty years later, Konrad Adenauer and Charles de Gaulle met to lay the first foundations of the European Union. Just over the hill to the

north is the awful memorial by which the Germans commemorated their victory over France in 1870, and the foundation of the Second Reich. The vineyards around have always been the fiefs of mighty magnates – Prince Frederick of Prussia, the Landgraf of Hessen, Prince Löwenstein, sundry counts and barons, descendants of Metternich.

Where else to drink my wine this time, then, but on the terrace of Schloss Johannisberg itself, which stands on its proud hill, rather like another triumphant memorial, surveying the Rhine below? The landscape is majestic. The scattered towns lie there like so many tenancies. The Rhine itself is power liquefied, marching down past the Lorelei to Koblenz and away to Rotterdam and the sea, alive with its constant stream of barges – whose chugging reaches me, like a hum of bees, above the calm of the vineyards. And look! There goes as telling a symbol of German continuity as you could ask for – the venerable paddle-steamer

Goethe

, 522 tons, streaming flags and foam, which has been sailing the Rhine in the service of the same owners since before the First World War.

I am looking at one of the Continent’s most fateful frontiers, and one of its most profitable conduits. It is the energy of all Europe that is streaming past down there. Beneath the flowering chestnuts on the belvedere of Schloss Johannisberg I pick up my bottle (with its elegant label of the Schloss itself, and its inscription

Fürst

von

Metternich

) as if I am about to pour an oblation. I have never in my life before tasted a top-class Rhine wine, and it precisely suits this high balcony of history. Rich and golden it flows into the glass, and it is a mighty wine, a noble wine, sweet but not sickly, complicated, a wine of elaborate consequence, such as bishops and margrave might toast Holy Roman Emperors in, or field marshals with big moustaches order to celebrate victories.

*

A blossom or two floats past me on to the trestle table. The

Goethe

is disappearing round the bend towards Rudesheim. Time to go home. Temporarily reassured by my European certainties, with the beauty of the organic, the elegance of self-esteem, the perverse grace of arrogance all blended in a profound continental aftertaste, I head for Wales, tea and game pie.

I saw Switzerland, although it had not joined what was then the European

Community, as epitomizing a profounder constancy of Europe. During the

1990s its reputation was tarnished rather by financial scandals and revelations

of wartime misbehaviour, but I wrote this piece in reaction to what I saw as

unfair and curmudgeonly foreign attitudes to the republic.

Weggis, said the road sign as I was driving south from Austria towards Geneva, and thinking the name had something amiably Dickensian about it, I turned off the highway and went down there to seek a bed for the night. I found myself in a flawlessly efficient family hotel on the shore of Lake Lucerne. Elderly paddle-steamers eased themselves past its gardens. A convention of insurance agents was taking time off in its lounges. Ladies in greyish cardigans strolled along the neighbouring promenade while waltzes sounded from a bandstand. Swans and ducks loitered, waiting to be fed by plump infants in pushchairs. A sense of sexless charm, kind but condescending, hung on the air like a hygienic perfume.

I found myself, in short, in a very nest, hive or cliché of the Swiss. I decided to give myself a few days there, and sort out the mixed feelings with which, as a member of the Welsh minority nation, I contemplate the matter of Swissness.

*

In British minds the very word is liable to raise emotions somewhere between sneer and mockery. It was not always so. In the Middle Ages the Swiss were respected as the fiercest and staunchest of soldiers, and in the nineteenth century Britons seem to have regarded the Helvetic Confederation with almost fulsome admiration. There was nothing sneerable about the Swiss then. They had achieved, it seemed, an ideal state. They were sturdy mountaineers and farmers, nature’s gentlemen. They could teach even Victorian Britain something when it came to mighty works of engineering, and the idea of an entire nation of citizen-soldiers powerfully appealed to the empire builders.

It was doubtless the two world wars that changed this reputation. To many Englishmen the principle of neutrality has always seemed cowardly, escapist or simply wet, and twice in this century it enabled the Swiss not only to avoid the tragedies that had befallen the rest of Europe, but even to profit from them. To the British, Swissness came to seem a less noble abstraction, and few phrases have more exactly expressed a national resentment than the famous remark about the creativity of the Swiss made in Carol Reed’s film

The Third

Man

: ‘They had 500 years of democracy and peace, and what did that produce? The cuckoo clock.’ Our great-grandfathers would have been astonished to hear it said, but Britons quote it even now,

and I remembered it often as I walked along the impeccable Weggis waterfront – the sour judgement of a battle-scarred, impoverished imperial kingdom of epic suffering and performance, about a comfortable, well-ordered, chocolaty republic which had not done a damned thing to help save civilization as we know it.

When those ancient tall-funnelled paddle-steamers docked at the Weggis pier, they were navigated by an officer standing all alone on a flying bridge, with a couple of levers and a long, highly polished speaking tube. He may never have sailed with an Arctic convoy, or taken a destroyer into Malta, but there was certainly nothing laughable about him, so coolly bringing his vessel to the quay. He looked proud, fit, competent and stylish. Style is not a word often associated with the Swiss, but for my tastes there is plenty of it around. The Swiss plutocracy does not flaunt its wealth with much flair – you will see more honest swank in half an hour on Sydney harbour than in a week beside Lake Lucerne – and the Swiss bourgeoisie seems determined never to break out of the ordinary. But Swissness in general does have aspects of true splendour.

Consider the Swiss chalet. Nowadays it is linked indissolubly with that miserable cuckoo clock, and it has been so trivialized by developers and speculative builders that it often has about as much dignity as a mullion-windowed executive residence on a housing estate in Dorking. All over Switzerland, though, examples of the real thing remain, and they are not just beautiful, but magnificent: they are stately homes

par

excellence

, heroic homes, built for men of stature by master craftsmen, as strong as they are hospitable, given individuality by endless variations of detail and decoration, and sometimes inhabited by the same family as long as any dukely house in England.

Or consider any of the high passes which link Switzerland with the cisalpine world. If they were marvels in Victorian times, they are prodigies today: with their superb roads and brilliantly lit tunnels, their railway lines circling in the hearts of mountains, their crowning forts, their tremendous sense of scale, purpose and infallible calculation, they suggest the constructions of a superpower, not a small land-locked republic of 6.5 million souls.