A Thousand Sisters (12 page)

Read A Thousand Sisters Online

Authors: Lisa Shannon

“Those two years. I live far away, so I've had no communication with my

family, only nurses and doctor take care of me. I want to see my family, but I'm scared to be taken again by those negative forces.”

family, only nurses and doctor take care of me. I want to see my family, but I'm scared to be taken again by those negative forces.”

“You say ânegative forces.' Who raped you?”

“Hutu.”

“Interahamwe?” I ask.

“Ndiyo.”

Yes.

Yes.

“When you think of the future, what do you hope for?”

“Only that I will recover. About the future, I'm waiting for God's plan.”

She looks out the window, tears wetting her face, “Up until now, my mind hasn't recovered. I'm still in a very unstable situation.”

The door opens and someone comes in to get Marie's toy frog.

The young woman continues crying, wiping her eyes with her scarf. “I am living, but I do not consider myself a human being. When I think about what happened to me, I feel as if my mind is far away. I think of the five men who had sex with me and I feel as if I was killed. Please think of me when you go back to America, because I don't expect to get out of this situation. I feel as if the Panzi Hospital will be my home forever. I have many difficulties . . . many wounds inside my vagina.”

How do I gently wrap this up?

I follow the nurse's lead by asking, “Would you sing a song for us?”

I follow the nurse's lead by asking, “Would you sing a song for us?”

She sings in a sweet, intimate voice: “When I remember the suffering I've had, I really weep. When I cry, I think about how I was suffering, because it was suffering in a true way.”

Â

AS I'M PACKING up my things, I notice a wiry braid and a party skirt peaking through a crack in the doorway. A little hand rests on the latch. Marie inches her head in for a moment and rubs the wall. She smiles and retreats behind the door, leaving only her hand to linger.

I call out to her, in a singsong voice. “Helloooo, Ma-rie . . .”

Her fingers creep back and rest on the crack in the doorway.

“Ma-rie-eee, where are you?”

I pull out the camera and find her hiding behind the door in the hallway. I flip the camera monitor toward her so she can see it. She squeals, delighted and intrigued. She follows the camera, watching herself as I record her. Maybe I'm playing with her, maybe I'm doing it for the sake of my own memory, but this is footage I swear I will never show anyone.

CHAPTER TEN

The Peanut Girl

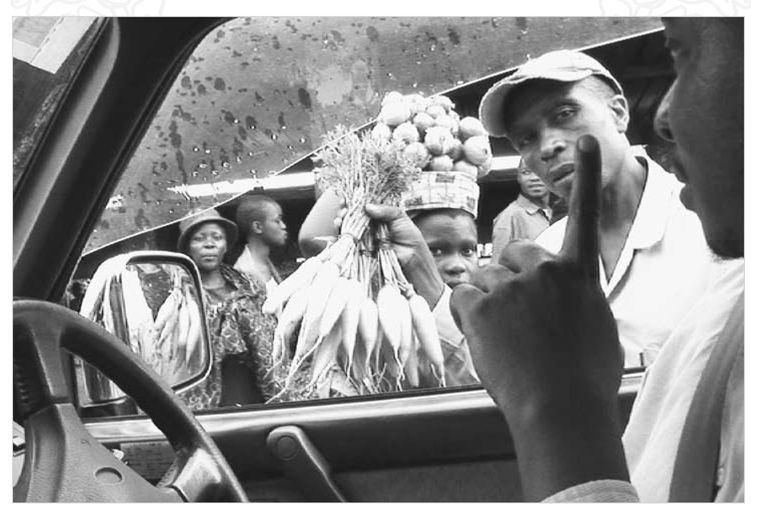

WE STOP AT

the market to buy peanuts and bread. I'm in the backseat, buried in my notes, waiting for Serge to return. When I look up, a girl, perhaps eleven, stands by my window staring. She doesn't hold up her hand, but she still appears to be a beggar. I drop my gaze back to my paperwork. As I look down at the paper, the image of her face registers. Hollow cheeks, closely shaved head. Thin. I look back up and survey her boney shoulders and arms. She is Ethiopia thin. Holocaust thin.

the market to buy peanuts and bread. I'm in the backseat, buried in my notes, waiting for Serge to return. When I look up, a girl, perhaps eleven, stands by my window staring. She doesn't hold up her hand, but she still appears to be a beggar. I drop my gaze back to my paperwork. As I look down at the paper, the image of her face registers. Hollow cheeks, closely shaved head. Thin. I look back up and survey her boney shoulders and arms. She is Ethiopia thin. Holocaust thin.

I ask Maurice to buy two extra pounds of peanuts. He hands me the bursting, soccer-ball-size plastic bag. The girl has abandoned her mission and retreated a few feet, so I turn to her and we lock stares. I invite her with a slight nod. Her eyes bulge for a second when she sees the nuts.

I unroll my window and slip the peanuts into her hands. As she grabs the bundle of protein and calories, Maurice almost squeals, giggling with delight. We pull away into the crowded Bukavu street and we are approaching the traffic circle when I think,

She's starving, and what do I give her? Peanuts.

She's starving, and what do I give her? Peanuts.

Let them eat peanuts. . . .

A moment later, we swing around to head back to Orchid and I see her again. She stands on the traffic median, grasping the bag of peanuts like it's a precious baby doll, digging her hand in and stuffing the nuts in her mouth by the fistful.

CHAPTER ELEVEN

Militias in the Mist

I'M CARSICK AS

I step out of the SUV following the thirty-mile drive on the bumpy, dusty, pothole-ridden, “jog-bra roads” (as one friend calls them). It has taken us an hour and a half to drive the thirty miles from Bukavu to the gates of Kahuzi Biega National Park with Eric, a local conservationist. We are in Congo's eastern forests, where Dian Fossey

(Gorillas in the Mist)

began her primate research; later, she was forced across the border to Rwanda, due to (surprise!) instability in Congo.

I step out of the SUV following the thirty-mile drive on the bumpy, dusty, pothole-ridden, “jog-bra roads” (as one friend calls them). It has taken us an hour and a half to drive the thirty miles from Bukavu to the gates of Kahuzi Biega National Park with Eric, a local conservationist. We are in Congo's eastern forests, where Dian Fossey

(Gorillas in the Mist)

began her primate research; later, she was forced across the border to Rwanda, due to (surprise!) instability in Congo.

A Canadian environmentalist friend asked me to check out Eric's programs for potential carbon-offset initiatives. The Congo basin forest is the second largest tropical forest in the worldâonly the Amazon is biggerâand the Democratic Republic of the Congo holds 8 percent of the world's carbon stores, making its preservation essential to solving the global climate crisis.

Eric is only three years older than I am, and his glowing, everyone-is-my-friend African smile shows no trace of war. In 1992, when he was twenty, Eric founded a small nonprofit dedicated to protecting gorillas and easing tensions between the park and his native community, which lies just outside the park gates.

I'm standing next to Eric in his field office just outside the park, in front of the first memorial I have seen in Congo: A wall lined with framed eight-by-ten photos of gorillas. “These are the gorillas killed in the park,” says Eric, and he speaks about each of them with the kind of affection people typically reserve for a beloved pet dog. “Ninja, killed April 1997 by rebels. Maheshe, 1993, poachers killed. Soso killed with her baby by rebels in 1998.”

A larger-than-life mural of gorillas graces the opposite wall, each animal with a name painted underneath. Shelves are lined with hand-carved elephants, rhinos, and chimps created in an initiative launched in Eric's first yearâan art program that trained poachers to carve souvenirs for tourists. The idea was that if these locals had another way to make a livingâthrough ecotourismâthey would give up poaching. The problem: Most of the tourists coming to the forests were being routed through Rwanda. In April 1994, tourism evaporated. Eric simply says, “The carving program went down.”

In July 1994, a flood of refugees came to these forests from Rwanda. Eric describes that time: “Three big, big, big camps were set up three kilometers from the park. The United Nations High Commission on Refugees helped facilitate them, in cooperation with the government. Not only did they come and stay in camps, they started cutting down trees in villages. Poaching activities increased; they were cutting trees from the park to make charcoal. Those people were looking for stuff in villages, like bananas or sticks or something. At first, they would say, âPlease help, I am a refugee.' Second, âDo you have some work? You can pay me a banana.' Sometimes they would steal. Most were respectful. We had respect for refugees. They were here under UN law.

“The camps remained for one and a half years.

“We knew them only as refugees under the UN structure, not as anything else. Then, in 1996, Kabila came with the Rwandan Army to fight President Mobutu and to chase refugees from the camps. The soldiers said, âThose are not refugees. It's Interahamwe, those who killed in Rwanda.' We were confused: Are they refugees or Interahamwe?

“The camps were in our village, so when they were chased, we were

chased together. It was nine in the morning. I was in my village, home with my parents, when we heard âTa, Ta, Ta, Ta.' Bullets. We took what we couldâlittle bags. I put mine on my back, my parents got theirs, and we went in the direction of the park, thinking we'd hide out in there. But when we went that way, we heard bombing ahead of us in the forest. We said, âNo, no, no. We'll die there.'

chased together. It was nine in the morning. I was in my village, home with my parents, when we heard âTa, Ta, Ta, Ta.' Bullets. We took what we couldâlittle bags. I put mine on my back, my parents got theirs, and we went in the direction of the park, thinking we'd hide out in there. But when we went that way, we heard bombing ahead of us in the forest. We said, âNo, no, no. We'll die there.'

“We went north, along the border of the park without knowing where we were going. Somewhere. We were tired. It was a whole day walking. It was getting dark. By that time, we were not with refugees. Everybody was saving himself. If we went in the park, they would be bombing. If we went down to the village, they would be fighting. We said, âWe'll stay here. If we get killed here, we accept it.'

“The next day, the fighting continued. We knew they were hunting refugees and soldiers, not Zairians, so three friends and I decided to try going home. When we arrived in our village, there were plenty of soldiers. We met some of them who said âYou. Stop.'

“We put our hands up. âWe are Zairians.'

“They said, âWhere are you going?'

“We told them, âWe are going home to get something for our families.'

“A Rwandan soldier asked us to show where we lived, to show them the key. They made us open the door. They said, âTell your family they can come back here. We are not against Zairians. We are against Interahamwe and Mobutu soldiers.'

“That evening we returned to the forest and told everyone we could to come back home. Many people were killed, though. They said, âI'm Zairian, I'm Zairian!' and the soldiers said, âNo, you look like Interahamwe. We will kill you.'

“In my village, nine guys were killed by the men of Rwanda or Kabila.”

“Did you see the Rwandan refugees again?” I ask.

“They were gone.”

It's a stunning thought. For a year and half, two million refugees were

camped out in Congo. Then, overnight, they were gone. “You have no idea where they went?”

camped out in Congo. Then, overnight, they were gone. “You have no idea where they went?”

“I heard on the radio they were killed or something.”

Â

THE CEMENT VISITOR'S CENTER at the park entrance displays a plaque that reads UNESCO WORLD HERITAGE SITE. Inside, the place is empty except for a few plastic chairs, the static video looping on a monitor in the corner, and two souvenirs for sale: one T-shirt and one book. I buy the book.

I walk into a room filled with skulls piled up to my chest: They're the skulls of gorillas, elephants, and antelope, all killed by poachers and militia. According to Eric, 450 elephants were killed between 1998 and 2003. The park's gorilla population has been cut in half since the war started, from 260 to the 130 remaining today.

“The Second War, the RCD war, was more destructive,” Eric tells me. “Many people were killed, not because they were Interahamwe or soldiers, but just because they were businessmen. You know, you would be killed because you had studied. It was like an operation to remove anyone who could have any influence.”

Eric is quiet for a moment. “Yeah. So many people died.”

He continues: “Since that time, insecurity began inside the park. Our access was very difficult because of many scenarios: looting in the park, people passing through the park and saying that refugees now are in the forest. [The refugees are] not well located, they need food; they are killing people, looting mines. Then they started attacking rangers in the park, even killing them, and going to surrounding villages to rape, loot, kill and return to the forest.

“Our work went very, very . . . down. We were looted, lost many things. We were afraid, a bit stressed. We developed a kind of cohabitation. When you knew there was a new

commandant

in the area, you could see him and try to make friendship to avoid any problem.

commandant

in the area, you could see him and try to make friendship to avoid any problem.

“Once, I went with two journalists to collect information on coltan

mining. Theoretically, the RCD wasn't there. But everyone there was in Rwandan formation.”

mining. Theoretically, the RCD wasn't there. But everyone there was in Rwandan formation.”

The Rwandan army in charge of a coltan mining site? Hmmm.

Whenever I speak to groups about Congo, some keen person in the back of the room always raises their hand and asks, “So who's making money off of all this?”

The Democratic Republic of the Congo is among the most mineral-rich countries on the planet. It has vast stores of more than 1,100 minerals, including diamonds, gold, copper, tin, cobalt, tungsten, and 15-20 percent of the world's tantalum, otherwise known as coltan, an essential semiconductor used in electronics like cell phones, laptops, video games, and digital cameras.

The United Nations has accused every nation involved in the conflict of using the war as a cover for looting. According to some estimates, armed groups make around US$185 million a year from the illegal trading of Congo's minerals. Countries like Rwanda have made hundreds of millions of dollars off of their Congo plunder. (For instance, Rwanda's primary tin mine produces about five tons per month. Yet over a six-month period, Rwanda reports 2,679 tons in tin exports.) According to UN reports, when Rwanda seized control of eastern Congo in the late 1990s, they smuggled hundreds of millions of dollars worth of coltan, cassiterite, and diamonds into Rwanda.

The New York Times

quotes one Rwandan government official as saying, “I used to see generals at the airport coming back from Congo with suitcases full of cash.”

The New York Times

quotes one Rwandan government official as saying, “I used to see generals at the airport coming back from Congo with suitcases full of cash.”

Other books

Love Doesn't Work by Henning Koch

Murder on Easter Island by Gary Conrad

Power & Majesty by Tansy Rayner Roberts

No Pity For the Dead by Nancy Herriman

Does This Beach Make Me Look Fat?: True Stories and Confessions by Lisa Scottoline, Francesca Serritella

The Sharpest Edge by Stephanie Rowe

This Wicked Magic by Michele Hauf

Sookie Stackhouse 8-copy Boxed Set by Charlaine Harris

My Favorite Fangs: The Story of the Von Trapp Family Vampires by Goldsher, Alan

30 Days of No Gossip by Stephanie Faris