A Field Guide to Lies: Critical Thinking in the Information Age (29 page)

Read A Field Guide to Lies: Critical Thinking in the Information Age Online

Authors: Daniel J. Levitin

From this report, it does sound as though he really did fast. A skeptic might discount his reports of pain and nausea as showmanship, but it is difficult to fake irregular heartbeat and weight loss.

But it’s the breath holding, televised on Oprah Winfrey’s show, that is the focus of Blaine’s TEDMED talk. In it, Blaine uses a lot of scientific and medical terminology to prop up the narrative that this was a medically based endurance demonstration, not a mere trick. Blaine describes the research he did:

“I met with a top neurosurgeon and I asked him how long . . . anything over six minutes you have a serious risk of hypoxic brain damage . . . perflubron.” Blaine mentions liquid breathing; a hypoxic tent to build up red blood cell count; pure 0

2

. That got him to fifteen minutes. He goes on to elaborate a training regimen in which he gradually built up to seventeen minutes. He throws out terms like “blood shunting” and “ischemia.” Did Blaine actually do what he said he did? Was the medical jargon he threw out for real, or just pseudoscientific babble he invoked to overwhelm, to make us

think

he knew what he was talking about?

As always, we start with a plausibility check. If you’ve ever tried holding your breath, you probably held out for half a minute—maybe even an entire minute. A bit of research reveals that professional pearl divers routinely hold their breaths for seven minutes. The world record for breath holding

before

Blaine’s was just under seventeen minutes. As you continue to read up on the topic, you’ll discover that there are two kinds of breath-holding competitions: plain

old, regular old breath holding, like you and your older brother did in the community pool when you were kids, and

aided

breath holding, in which competitors are allowed to do things like inhale 100 percent pure oxygen for half an hour prior to competing. This is sounding more plausible, but how far can you get with aided breath holding—can it actually bridge the gap between a few minutes and seventeen minutes? At this point, you might try to learn what the experts have to say—pulmonologists (who would know something about lung capacity and the breathing reflex) and neurologists (who would know how long the brain can last without an influx of oxygen). The two pulmonologists I checked with described a training regimen much like the one Blaine describes in his video; both felt that with these “tricks” or special measures, seventeen minutes of breath holding would be possible. Indeed,

Blaine’s record was broken in 2012 by Stig Severinsen, who held his breath for twenty minutes and ten seconds (after inhaling pure oxygen, of course), and who then broke his own record a month later, achieving twenty-two minutes. David Eidelman, MD, a pulmonary specialist and dean of the McGill Medical School said: “I agree that it does sound hard to believe. . . . However, by inhaling oxygen first, fasting, and using yoga-type techniques to lower metabolic rate while holding one’s breath underwater, it seems that this is possible. So, while I retain some skepticism, I do not think I can prove it is impossible.”

Charles Fuller, MD, a pulmonary specialist at UC Davis, adds, “There is sufficient evidence to indicate that Blaine is being truthful, as this event is physiologically feasible. Given the caveat that Blaine is a magician and there could have been other contributing factors to his successful seventeen-minute breath hold, there is also ample physiological evidence that this feat could have been accomplished. There

is a subset of people in the breath-hold world who vie for a record officially known as ‘pre-oxygenated static apnea.’ In this event, breath holding is sponsored by Guinness World Records, as sports divers consider this cheating. Breath-hold duration is measured after hyperventilating (blowing of carbon dioxide) for thirty minutes while breathing 100 percent pure oxygen. Further, the event is typically held in a warm pool (which reduces metabolic oxygen demand), with the head held just below the surface, which induces the human dive reflex (further depressing metabolic oxygen demand). In other words, all ‘tricks’ which extend the human capacity for conscious breath hold. Most importantly, prior to Blaine, the record was just under his seventeen minutes [by an athlete who was

not

a magician], and there are additional individuals who have now been recorded for longer breath holds in excess of twenty minutes. Thus, ample evidence that this feat could have been accomplished as claimed.”

So far, Blaine’s story seems plausible, and his talk hits all the right notes. But what about brain damage? Blaine himself mentioned this as a problem. You’ve no doubt heard that if the brain loses oxygen for even three minutes, irreparable damage and brain death can occur. If you’re not breathing for seventeen minutes, how do you prevent brain death? A good question for a neurologist.

Scott Grafton, MD: “Oxygen doesn’t stay in the blood all by itself. Think oil and water. It will quickly diffuse out of the liquid blood—it needs to bind to something. Blood carries red cells. Each red cell is loaded with hemoglobin (Hgb) molecules. These hemoglobin molecules can potentially bind up to four oxygen molecules. Each time a red cell passes through the lungs, the number of Hgb molecules with oxygen bound to them increases. The stronger the concentration of oxygen in the air, the more Hgb molecules will bind to it. So load ’em up! Breathe 100 percent oxygen for thirty minutes so that total oxygen binding is as close to 100 percent saturation as you can get.

“Each time the red cell passes through the brain, oxygen will have a probability of unbinding from the molecule, diffusing across cell membranes to enter the brain tissue, where it binds to other molecules that use it in oxidative metabolism. The probability of a given oxygen molecule unbinding from hemoglobin and diffusing is a function of the relative difference of oxygen concentration on either side of the membranes.”

In other words, the more oxygen the brain needs, the more likely it will be to pull oxygen out of hemoglobin. By breathing pure oxygen for thirty minutes, the competitive breath holder will maximize the amount of oxygen in the brain

and

in the blood. Then, once the breath-holding event starts, oxygen levels in the brain will decrease as they normally do over time, and the competitive breath holder will very efficiently pull out whatever oxygen happens to be left in hemoglobin to oxygenate the brain.

Grafton continues, “Not all the hemoglobin molecules are loaded up with oxygen on each pass through the lungs, and not all of them unload on each pass through the organs. It takes quite a few passes to unload all of them. When we say that brain death happens quickly due to a lack of oxygen, it is usually in the context of a lack of circulation (heart attack) when the heart is no longer delivering blood to the brain. Stop the pump, and no red cells are available to offer up oxygen and brain tissue dies fast. In a person submerged, there is a race between brain injury and pump failure.

“One key trick: The muscles need to be at rest. Muscles are loaded with myoglobin, which holds on to oxygen four times more strongly than red-cell hemoglobin does. If you’re using your muscles, this

will accelerate the loss of oxygen overall. Keep muscle demand low.” This is the

static

in the static apnea that Dr. Fuller mentioned.

So from a medical standpoint, David Blaine’s claim appears plausible. That might be the end of the story, except for this.

An article in the

Dallas Observer

claims the breath holding was a trick, and that Blaine—a master illusionist—used a well-hidden breathing tube. There’s nothing about this in other mainstream media, which doesn’t mean the

Observer

is wrong, of course, but why is this paper the only one reporting it? Perhaps a magician who performs a trick but claims it wasn’t one is not big news.

Reporter John Tierney traveled to Grand Cayman Island to write about Blaine’s

preparation for the breath holding for an article in the

New York Times,

and then wrote about

the

Oprah

appearance in his blog a week later. Tierney makes a lot out of Blaine’s heart rate, as reported on a monitor next to his tank on the Winfrey show,

but as with the ice-block demonstration, there’s no evidence this monitor was actually connected to Blaine, and it might really have been more for showmanship—to make the audience think that the conditions were really rough (a standard practice for magicians). Neither Tierney nor a physician involved in the training mention how closely they were monitoring Blaine during practice trials in the Caymans—it’s possible that they took him at his word that he didn’t have any apparatus. Perhaps the real motive of this training was that Blaine figured if he could fool

them,

he could fool a television audience.

Tierney writes, “I was there at the pool along with some free-divers who are experts at static apnea (holding your breath while remaining immobile). Dr. Ralph Potkin, a pulmonologist who studies breath holding and is the team physician for the United States free-diving team, attached electrodes to Blaine’s body during the session and measured his heart, blood, and breathing as Blaine kept his head submerged in the water for sixteen minutes.

“I’ve always been skeptical of cons—I did a long piece on James Randi a while back, and was with him in Detroit when he was exposing an evangelist named Peter Popoff—but I saw no reason to doubt Blaine’s feat. His breath hold in front of me was done in clear water in the shallow end of the very ordinary swimming pool at our hotel, with experts in breath holding a few feet away watching him all the time. His nose and mouth were clearly below the water—but just a couple of inches, so they were visible at all times. You tell me how he snuck a breathing tube in there so that no one noticed it or any bubbles. Magicians fool people by distracting them with motions and patter, but the whole point of static apnea is to remain absolutely motionless in order to conserve oxygen, which is what David did. (It’s remarkable what a difference that makes—the

trainers who were working with David did a short session with me and my photographer. We pre-breathed air instead of oxygen, but we were amazed at how long we went—I got up to 3 minutes and 41 seconds, and the photographer even longer.)”

So now the

Dallas Observer

says it was faked, and a

New York Times

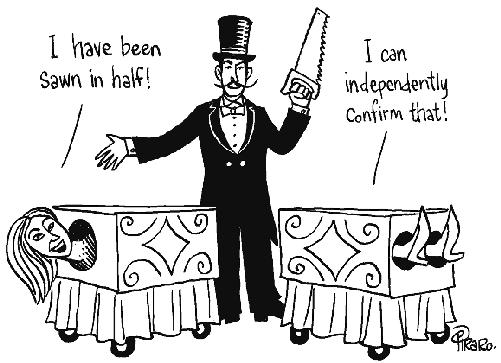

reporter seems to believe it wasn’t. What do professional magicians think? I spoke to four. One said, “It’s got to be a trick. A lot of his demonstrations are known, at least within the magic community, to use camera trickery and [a] very involved setup. It would be very easy for him to have a breathing tube that allows him to take oxygen in, and to exhale carbon dioxide, without making bubbles in the water. And if he practices, he wouldn’t need to be doing it all that often—he could actually hold his breath for a minute or two at a time in between tube breaths. And there could be other camera trickery—he might not actually be in the water! Projection or green screen could make it appear that he was.”

The second magician, who had worked with Blaine a decade earlier, added, “His hero is Houdini, who became famous for doing stunts. Houdini made a reputation in part by doing things that people did in the 1920s—flagpole sitting and so on. Some do require endurance and some are faked slightly; some aren’t as hard as you’d think, but most people never try them. I don’t see why Blaine would fake the block-of-ice trick—that one is simple because of the igloo effect—it’s not actually that cold in there. It

looks

impressive. If he was in a freezer that would be different.

“But seventeen-minute breath holding? If he can super-oxygenate his blood, that can help. I know that he does train and does some things that are remarkable. But I’m sure the breath-

holding trick is partly enabled. He does hold his breath, I think, but not 100 percent of the time. It’s quite easy to fake. He probably has [a] breathing tube and other apparatus.

“Note that a lot of his magic is on TV and there are edits at key points. We assume it’s real information and we’re seeing everything because that’s how our brains construct reality. But as a magician, I see the edits and wonder what was happening during the missing footage.”

A third magician added, “Why would you go to all the trouble to train if, as an illusionist, you can do it with equipment? Using equipment creates a more reliable, replicable performance that you can do again and again. Then, you just need to act as though you’re in pain, dizzy, disoriented, and as though you’ve pushed your body beyond all reasonable limits. As an entertainer, you wouldn’t want to leave anything to chance—there’s too much at stake.”

The fact that no one reports seeing David Blaine use a breathing tube does not constitute evidence that he didn’t, because it is precisely the

job

of illusionists to play tricks with what you see and what you think you see. And the illusion is even more powerful when it happens to you. I’ve had the magician Glenn Falkenstein read off the serial numbers of dollar bills in my wallet from across the room while he was blindfolded. I’ve had the magician Tom Nixon place the seven of diamonds in my hand, yet a few minutes later it had become a completely different card without my being aware of him touching me or the card. I know he’s switching the card at some point, but even after having the trick done to me five times, and watching it performed on other people many more times, I still don’t know when the switch occurs. That is part of the

magician’s genius, and part of the entertainment. I don’t think for a moment that Falkenstein or Nixon possess occult powers. I know it’s entertainment, and they sell it as that.