97 Orchard: An Edible History of Five Immigrant Families in One New York Tenement (28 page)

Read 97 Orchard: An Edible History of Five Immigrant Families in One New York Tenement Online

Authors: Jane Ziegelman

Tags: #General, #Cooking, #19th Century, #History: American, #United States - State & Local - General, #United States - 19th Century, #Social History, #Lower East Side (New York, #Emigration & Immigration, #Social Science, #Nutrition, #New York - Local History, #New York, #N.Y.), #State & Local, #Agriculture & Food, #Food habits, #Immigrants, #United States, #Middle Atlantic, #History, #History - U.S., #United States - State & Local - Middle Atlantic, #New York (State)

The Italian writer Jerre Mangione, who grew up in Rochester, New York, in the 1920s, remembers the parade of courses: first, there was soup; then pasta, perhaps ziti in

sugo

; followed by two kinds of chicken, one boiled, and one roasted; roasted veal; roasted lamb; and

brusciuluna

—“a combination of Roman cheese, salami, and moon-shaped slivers of hardboiled egg encased in rolls of beef.” When the meat was cleared, there was fennel and celery to cleanse the palate, followed by homemade pastries, nuts, fruit, and vermouth. These Sunday suppers, prepared by the author’s father, were more extravagant than the family could realistically afford, and the senior Mangione often had to borrow money to pay for them.

8

Moderation had no place at the Sunday table. The gathered crowd, encouraged by their fellow diners, went back for multiple helpings with not a jot of self-consciousness. Quite the contrary, any guest who refused another helping was given a mild rebuke.

The meatballs,

ragu

s, and roasts that were (and remain) a centerpiece of the Italian-American kitchen had never figured in the peasant diet. Rather, they belonged to the kitchens of Italian landowners, merchants, and clergy, who, on important feast days like Easter and Christmas, distributed meat to the poor.

9

In America, immigrant cooks reinterpreted these feast-day foods and, in another expression of American bounty, made them a regular part of the Sunday table. The American larder was so immense that it could literally feed the working class on a diet once reserved for Italian nobility.

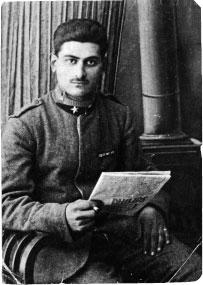

One effect of the quota laws of the 1920s was to create a shadow wave of uncounted immigrants, men and women from Russia, Poland, Italy, and other restricted nations, who evaded the authorities and entered the country illegally. The Baldizzis belonged to that wave. Adolfo Baldizzi was born in Palermo in 1896 and was orphaned as a young boy. His professional training as a cabinetmaker began at age five, but the outbreak of World War I put his career temporarily on hold. A wartime portrait of Adolfo shows a young soldier with thick black hair and a neatly trimmed mustache. Rosaria Baldizzi (her family name was Mutolo) was born in 1906, also in Palermo, to a family of trades people and civil servants. The Baldizzis were married in 1922, the same year Rosaria turned sixteen. A year later, the couple decided to emigrate. To evade the 1921 immigrant quota laws, Adolfo came to America as a stowaway aboard a French vessel. As the ship pulled into New York Harbor, he climbed from his hiding place, jumped over the railing, and swam to shore. Rosaria made the same trip in 1924, with a doctored passport.

Adolfo Baldizzi in his soldier’s uniform, circa 1914.

Courtesy of the Tenement Museum

Wedding portrait of sixteen-year-old Rosaria Mutolo Baldizzi, two years before she emigrated.

Courtesy of the Tenement Museum

For Rosaria Mutolo Baldizzi, the move to America was a step down in life. Born to a middle-class family, Rosaria spent her childhood in a good-size house with a stone courtyard where her mother grew geraniums and raised chickens, selling the eggs to neighbors. Rosaria’s father was confined to a wheelchair by the time she was a young girl, but in his youth had owned or worked in a bakery. Her two older brothers were both policemen; her sister was a dressmaker. On Sunday afternoons, still in their church clothes, the family took leisurely strolls, stopping at a local café for coffee and granita. Rosaria’s marriage to a cabinetmaker at age sixteen was considered a good match. In her 1921 wedding portrait, she is posed at the foot of an ornate staircase, dressed in a tailored skirt and matching jacket, both trimmed in a wide panel of hand-woven lace. A flapper-style cloche hat, jauntily cocked, with a long, trailing sash, completes the ensemble.

Rosaria’s move to New York in 1924 meant the end of a reasonably privileged and protected life. Her first glimpse of Elizabeth Street, center of Sicilian New York, was a sobering experience for the young immigrant. To her consternation, the shoppers who overflowed the sidewalk onto the cobblestoned street were oblivious to the garbage under their feet, a carpet of moldering cabbage leaves and orange rinds. Every window ledge and door lintel was veiled in soot, like a dusting of black snow. But most disturbing of all were the Elizabeth Street stables. The young Mrs. Baldizzi was shocked to find that New Yorkers, presumably civilized people, lived side by side with horses.

The couple’s first home was a single room in a two-room apartment. To supplement her husband’s earnings, Rosaria took in laundry, a common source of income for immigrant women. Whenever the couple fell behind in rent, they simply packed up and moved. The two Baldizzi children, Josephine and John, were born on Elizabeth Street, but in 1928, when John was still in his swaddling clothes, the family left Little Italy for 97 Orchard Street, a leap across cultures that brought the Baldizzis into the heart of the Jewish Lower East Side. Living on Orchard Street, they encountered the challenges typical of an immigrant family. These were eclipsed, however, by the calamitous events of 1929 and their aftermath. The “land of opportunity” they had expected to find evaporated before their eyes, leaving Mr. Baldizzi with a wife, two toddlers, and little hope of finding work.

The Baldizzis remained on Orchard Street through the grimmest years of the Depression. For most of that time, Adolfo was unemployed, though he still earned a few dollars a week as a neighborhood handy-man. New clothes or toys for the children were out of the question. When the soles on Josephine’s shoes sprouted holes, they were fortified with a cardboard insert. The family food budget was concentrated on a few indispensible staples: bread, pasta, beans, lentils, and olive oil. Once a week, the family received free groceries from Home Relief, the assistance program created by Franklin Roosevelt in 1931 when he was still governor of New York. For many foreign-born Americans, Home Relief introduced the immigrant to foods like oatmeal, butter, American cheese, and, for the children, cod liver oil. It also furnished them with milk, potatoes, vegetables, flour, eggs, meat, and fish. For the Baldizzi parents, the weekly trip to the neighborhood food bank (it was actually the children’s school) was a public walk of shame. The food, however, was necessary, and they accepted it gratefully.

Breakfast for the Baldizzi children was hot cereal, courtesy of Home Relief, or day-old bread that Mrs. Baldizzi tore into pieces and soaked in hot milk, with a little butter and sugar. The resulting dish, a kind of breakfast pudding, was a favorite of the children. Josephine Baldizzi, who was always thought too skinny by her parents, was given raw eggs to help fatten her up. The eggs were eaten two ways. Mrs. Baldizzi would poke a hole in one end of the egg, instructing her daughter to suck out the nutritious insides. She also prepared a drink for Josephine made of raw egg and milk whipped together with sugar and a splash of Marsala wine. Breakfast for the parents was hard bread dipped in coffee that Mrs. Baldizzi boiled in a pot. Coffee grinds, like tea bags, were reused two or three times before being consigned to the trash. The Baldizzi children returned home for a lunch of fried eggs and potato, or vegetable frittata. A typical evening meal was pasta and lentils or vegetable soup, which Mr. Baldizzi referred to as “belly wash.” On Saturday evenings, he made the family scrambled egg sandwiches with American ketchup.

Though America’s bounty eluded the Baldizzis, Rosaria understood the power of food over the human psyche and used it—what little she had—as an antidote to the daily humiliations of poverty. Dinner in the Baldizzi household was a formal event, the table set with the good Italian linen that Rosaria had brought over from Sicily, the napkins ironed and starched so they stood up on their own. If the menu was limited, the food was expertly cooked and regally presented. On occasion, as a treat for the children, Rosaria would arrange their dinners on individual trays and present it to them as edible gifts. One of Josephine’s clearest childhood memories is of her mother standing in front of the black stove at 97 Orchard, holding a tray of “pizza”—a large round loaf of Sicilian bread, sliced crosswise like a hamburger bun, rubbed with olive oil, sprinkled with cheese, and baked in the oven. “You see,” Rosaria says, “you

are

somebody!” Such was the power of food in the immigrant kitchen: to confer dignity on a skinny tenement kid with cardboard soles in her shoes.

On birthdays and holidays, edible gift–giving rose to the level of ritual. For All Souls Day, when ancestral spirits deigned to visit the living, Mrs. Baldizzi gave the kids a tray piled with the candied almonds known as

confetti

,

torrone

, Indian nuts, and Josephine’s personal favorite, one-cent Hooten Bars. That night, the children would slip the tray under the bed, in case the spirits should arrive hungry. The next day, after the ancestors had presumably helped themselves, it was the children’s turn. On Easter, each child received a marzipan representation of the Paschal lamb. Candy was also part of the Nativity scene displayed each December on the Baldizzis’ kitchen table, the manger strewn with

confetti

and American-style peppermint drops.

Much of the candy sold in New York in the early twentieth century—Italian and otherwise—was produced locally in factories scattered through the city. In fact, by the turn of the century, New York was the center of the American candy trade, employing more people than any other food-related industry aside from bread. New York candy-makers were tied to another local industry with deep historical roots: the sugar trade. All through the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries, ships carrying raw sugar from the Caribbean delivered their cargo to the refineries or “sugar houses” that were clustered near Wall Street, converting the coarse brown crystals into loaves of white table sugar. Candy factories began to appear in Lower Manhattan in the early 1800s, before migrating uptown to Astor Place, then to midtown and Brooklyn.

By the late nineteenth century, immigrants were important players in the candy business. Some owned factories specializing in their native sweets, but many, many more worked as candy laborers. In New York, Chicago, Boston, and Philadelphia, all major candy-making cities, foreign-born women, chiefly Italians and Poles, worked the assembly lines, dipping, wrapping, and boxing.

Italian Women in Industry

, a study published in 1919 that looked specifically at New York, reported that 94 percent of all Italian working women in 1900 were engaged in some form of manufacturing. While the overwhelming majority worked in the needle trades, about 6 percent were candy workers, a job that required no prior training or skills. The dirtiest, most onerous jobs—peeling coconuts, cracking almonds, and sorting peanuts—went to the older women who spoke no English. For their labor, they were paid roughly $4.50 for a sixty-five-hour workweek. (Women who worked in the needle trades generally earned $8 a week, while sewing machine operators, the most skilled garment workers, brought in $12 weekly or more.) The long hours and filthy conditions in the factories made candy work one of the least desirable jobs for Italian women. Mothers who worked in the candy factories for most of their adult lives prayed that daughters “would never go into it, unless they were forced to.”

Another class of candy workers could be found in the tenements. Candy outworkers were immigrant women hired by the factories, who brought their work home to their tenement apartments, completing specific tasks within the larger manufacturing process. This two-tiered arrangement of factory workers and home workers was widespread on the Lower East Side and used by several of the most important local industries. The largest and best-documented was the garment industry, in which factory hands were responsible for the more critical jobs of cutting, sewing, and pressing, while home workers did “finishing work”: small, repetitive tasks, like sewing on buttons, stitching buttonholes, and pulling out basting threads, a job that often fell to children. In the candy trade, finishing work meant wrapping candies and boxing them. It also included nut-picking: carefully separating the meat from the nutshell with the help of an improvised tool, like a hairpin or a nail. These were jobs often performed as a family activity, by an Italian mother and her kids, sitting at the kitchen table with a fifty-pound bag of licorice drops lugged home from the factory that morning, a small mountain of boxes at their feet.