1636: Seas of Fortune (14 page)

Read 1636: Seas of Fortune Online

Authors: Iver P. Cooper

Tags: #Fiction, #Science Fiction, #General, #Alternative History, #Action & Adventure

“But we could at least agree to remain neutral in the absence of a direct order from our sovereign, and, in the event of such an order, give notice of intent to dissolve our pact.”

David looked thoughtful. “It wouldn’t be easy for you to receive such an order, considering that we control your line of communication.”

“No, it wouldn’t. So the agreement will be more to your benefit than ours, but at least would save our honor.”

“I will think on it. While it is a tempting prospect—trade, and exchange of information, would be mutually beneficial, I think—the feelings of the Dutch of the colony run high. And we won’t always have warships in the river; there would be a fear that you would try to take advantage if they were absent.”

Maria moved her chair. The screech drew all eyes to her. “But gentlemen, there is another factor to consider. As a Dutch woman, I was of course appalled by the treacherous attack on our fleet. But I understand that the English in turn are still fired by the incident at Amboyna.”

“The massacre—” began Scott, but he desisted when Marshall gripped his shoulder.

“Still, in the long-term, they have a common enemy: the Spanish. The French, too. I think that upon more mature reflection, you will realize that your long-term interests lie with us. Us, meaning the USE and its allies.”

Marshall steepled his fingers. “How so?”

“I doubt very much that your king cares what happens to you. Because he has already given up North America to the French.”

“The French!”

“Yes, by the Treaty of Ostend, which we learned about shortly after the Battle of Dunkirk. Charles discovered that in the Grantville history books, some of the American colonies revolted successfully, and so he was willing to let them be Richelieu’s problem.”

“You have proof of this?”

“Sorry, no, but you may question the crew or the colonists,” David said.

“You can do better than that,” Maria interjected. “Didn’t you save the newspapers? You said you would save them until the Spanish had been defeated!”

David swore. “You’re right, of course.” He dug them out and handed them to Marshall and Scott.

When they finished reading, he added, “Charles also found out that, according to those history books, he gets into a fight with Parliament, which ends with his head on the chopping block. So he’s brought in mercenaries to control London, and he’s been arresting anyone who the up-timers’ books identified as a Parliamentarian. Indeed, anyone he thinks likely to have such sympathies.”

Marshall winced. “Do you know anything of the Earl of Warwick?” Maria shook her head.

“Warwick, Warwick,” mused David. “Oh, Robert Rich. Well, what I know about him is that he is a big investor in New World colonies. Bermuda, and Providence Island, off the coast of Nicaragua. And, yes, Richneck Plantation, on the James, is his. I spent a few weeks in Virginia in March of ’33. Why do you ask?”

“He is our chief benefactor,” Marshall admitted. “And a Puritan, as are we.”

Scott didn’t look happy. “He is on the outs with the Court. Opposed the forced loan of 1626. And Laud’s repression of the Puritans.”

“So what you can expect,” said David, “is that either your colony, too, will be turned over to the French, or it will be given as a reward to one of Laud’s or Wentworth’s cronies.”

* * *

Heinrich coughed. “Begging your pardon, Madam Vorst, but the captain wants to see you.”

Maria looked wistfully at the scarlet ibis that stood rock-still in the pond some yards away, watching for an unwary frog. She had just set up her easel, and had been looking forward to painting the beautiful bird. But she doubted it would hang around waiting for her to finish the captain’s business, whatever it was. Answering a gardening question for colonists, perhaps. She knew that she wouldn’t have had the opportunity to study the natural world of Suriname if it weren’t for the colony, but sometimes her role of “science officer” was irksome.

She rose to her feet, and the sudden movement startled the bird, causing it to take flight. “Help me gather up my things, will you?”

* * *

The captain didn’t beat around the bush. “Scott’s staying in Gustavus, as the representative of the Marshall’s Creek colonists.”

Maria raised an eyebrow. “As a hostage, too, I imagine.”

David nodded. “Marshall’s going back upriver on the

Eikhoorn

, to explain the situation to them and see if they wanted to throw in with us.”

“Really. Then perhaps I should go upriver with him. Their fort is on the fringe of the rainforest. I might be able to find rubber trees with their help. Or at least the help of their Indian allies.”

“Are you sure? We don’t know how they’ll react to the news. The crew of the

Eikhoorn

will be outnumbered.”

“Captain Marshall seems a man of honor; I will make sure that I am traveling under his protection. And even the Spaniards, when they attack a foreign colony, will usually spare the women.”

“You’ll be the only woman there.”

“I am sure there were Indian women around, they just stayed out of sight on your last visit. And as I said, I will be with Captain Marshall.”

David hesitated.

“It’s not just that the USE needs the rubber. If I find them a new product to sell to us, that will help reconcile them to the ‘Swedish’ presence downriver. Or whatever you want to call it.”

“Okay. You’ve convinced me.”

* * *

“This is

so

slow,” said David.

“Slow but sure,” Maria replied.

They were watching latex slowly drip from the gash in the tree, into a waiting cup. With the aid of Maria’s sketches, themselves based on illustrations in the Grantville encyclopedias, the Indians had been able to locate several different trees of interest. One, the

Hevea guianensis

, produced true rubber. Another was what the encyclopedias called

Manilkara bidentata

. Its latex hardened to form balata. Balata wasn’t elastic, but it was a natural plastic, which could be used for electrical insulation.

“Why don’t we just chop the tree down and take all its latex at once?”

“Several reasons,” said Maria. “They aren’t that common, just a few trees an acre, so we would have to go farther and farther out to find more. If we tap them, each tree will produce rubber for twenty years or more. And finally, it just won’t work. The latex is stored in little pockets. It’s not like there’s a big cavern inside you can chop your way to. If you want a quick return, you need to find a

Castilla elastica

, it has nice long tubes.”

“Well, this is too slow for me. It’s as exciting as watching paint dry,” David declared. “I think it’s time for me to head out.”

“Back to Gustavus?”

“No, on to Trinidad and Nicaragua. And pick up a Spanish prize or two along the way, if we’re lucky.”

“If we must,” said Maria with a sigh. “But I have such a horrible backlog of plants to study. Lolly told me the rainforest was diverse, and I thought I knew what she meant, but the reality is inconceivable if you don’t see it with your own eyes.”

“Who said you had to leave?”

“You need me to find the

Castilla

in Nicaragua.”

“No, I don’t. I have Philip.”

Maria opened her mouth, then shut it without saying anything.

“And he has to come with me because he has to go home at the earliest opportunity. Even if he is dreading the parental punishments that await him.”

* * *

“Philip.”

“Yes, Maria?” He eased the rucksack he was carrying down to the ground. “As you can see, I am packed and ready to go back to sea.”

“I am sorry it didn’t work out. Couldn’t work out. You and me, that is.”

Philip didn’t quite meet her eyes. “I know. I made an idiot out of myself.”

“Don’t feel bad. You’re a teenage male. Teenage males, by definition, are idiots. Whatever century they were born in.”

“Thanks. I think.”

“Anyway, I have a present for you.” She brought forward the object she had been hiding behind her back. It was one of the blank journal books she used for drawing.

“You can use this to keep track of what you see and do. Perhaps it will make you famous. And . . . and I will enjoy reading it one day.”

He took the journal, brushing her fingers as he did so. “Thank you. I mean it. And good luck.”

He paused. “Heyndrick seems like an okay guy.”

“I think so, too.”

* * *

David studied his cousin. “You’re determined to stay here in Suriname?”

“Yes. I think there is a lot of opportunity here,” said Heyndrick, straight-faced.

“You’re blushing.”

“I am not,” said Heyndrick, coloring still more deeply.

“I am naming you as acting governor, but—you intend to escort Maria on her explorations?”

Heyndrick nodded.

“I thought so. We need someone to keep a steady hand here in your absence. I think I will appoint Carsten Claus as your deputy.”

“The ex-sailor? Ran away from the farm as a kid, and later thought better of it?”

“That’s right. He is CoC. An organizer of some kind. He is chummy with Andy Yost.” Andy was the owner of the Grantville Freedom Arches, the first headquarters of the CoC.

“And you let him come on board?”

“There’s CoC money invested in this colony. And the up-timers are counting on the CoC to make sure we don’t make any, uh, imprudent investments.”

“Buying slaves, you mean?”

“That’s right. I will leave you one of the yachts. You and Maria can use it for exploring. You’ll have to keep the captain, of course, I don’t have good reason to deprive any of them of command. Which one do you want?”

“The

Eikhoorn

.”

“I am not surprised.” Heyndrick blushed again. The

Eikhoorn

was commanded by Captain Adrienszoon, a man thirty years older than Heyndrick, while the

Hoop

had a young, unmarried skipper.

Heyndrick pulled a map out of its case, and flattened it out. “Are you sure you shouldn’t stay until July or August? See the colony through the end of the first wet season?”

“No. If I wait, I will be in the Caribbean in the hurricane season. Not a wise idea.”

Heyndrick found Trinidad on the map, grunted, and rolled the map up again. “That’s true . . . However . . . David, I have sailed with you for a long time. And there is something I think needs saying, although I doubt you’d like to hear it.”

“Out with it, Cuz.”

“You want to be a patroon. But we know how often colonies with absentee owners have come to grief. Someone like Jan Bicker can afford a loss, but you can’t. You’re terrific at managing sailors and settlers and Indians, but you need to manage yourself. After a few months, you go crazy and want to sail off. And next you know it, your colony, your investment, will be gone.”

“So what do you suggest?”

“I know you have to, what’s the American phrase, ‘get the ball rolling’ in Trinidad and Nicaragua. And then you want to get the rubber and tar to the Americans as quickly as possible. But after that, please plan on coming back here, and staying as governor. At least for a few years.”

“I’ll think about it. But it is a waste of my skills as a shiphandler.”

“Then perhaps you need to forget about being a patroon, and stick to what you do best.”

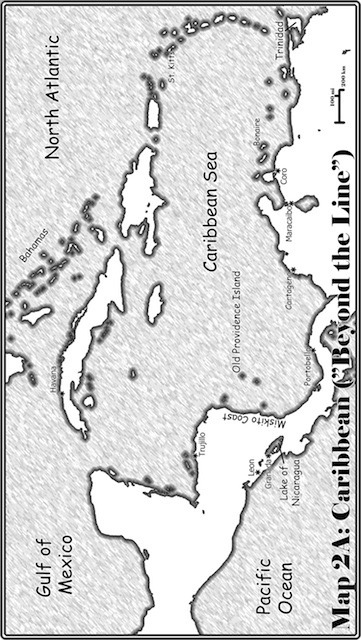

Map 2A: Caribbean

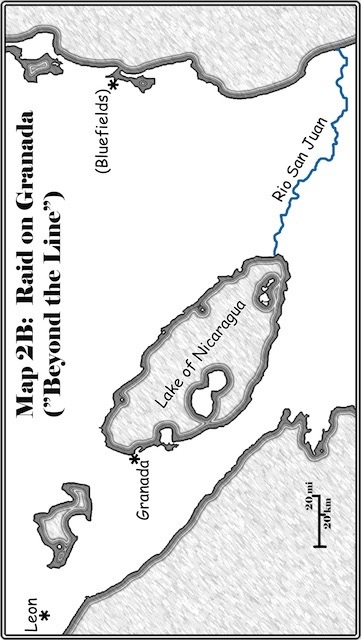

Map 2B: Raid on Granada

Beyond the Line

April 1634 to Late 1634

Trinidad, April 1634

It was a lake, but one unlike any other they had seen. This was the famous Pitch Lake of Trinidad. A hundred acres of tar.

David Pieterszoon de Vries, captain of the fluyt

Walvis

, studied it for a few moments. The lake was nearly circular, perhaps two thousand feet across, nestled in a shallow bowl at the top of a hill. The surface wasn’t flat and still, like a mountain lake protected by hills from the wind. Instead, there were broad, dark folds, with clear rainwater lying in the hollows between them. David, in his youth, had worked for a bookseller, to learn English, and the haphazard folding reminded him of marbled paper. Here and there, the folds were festooned with a patch of grass, a few yards in width, with a shrub or small tree rising above it like the mast of a ship.

For Philip Jenkins, born in twentieth-century West Virginia, it awoke other memories. “This is a humongous parking lot.”

“Sir Walter was right,” said David. “Enough pitch here for all the ships of the world.” Sir Walter Raleigh had come here in 1595; his sailors used its tar to protect their ships’ hulls from the

teredos

, the wood borers of the tropical waters.

“We have a lot more uses for it than for caulking ships,” Philip replied.

“Wait here.” Using a boarding pike as a probe, David tested the surface. It seemed firm enough. He took a step forward. The tar sank slightly, but held his weight. He took a second step. No problem.

David turned his head. “Follow me. Test the ground before you trust yourself to it, there may be softer areas at the center of the lake.” After a moment’s hesitation, the landing party followed him.

* * *

Philip was surprised to discover that the tar didn’t seem to stick to his shoes or clothing, as he would have expected. Inspected closely, the tar was finely wrinkled, like the skin of an elephant.

David and his landing party walked around a bit, then he called them to a halt. “One spot seems as good as another, so let’s start here.” The sailors broke up the tar with picks, then drove their shovels into the bitumen, lifting out masses of dark goo. They dumped them into the waiting wheelbarrows. Philip wrinkled his nose; the disturbance of the lake surface had brought forth a sulphurous smell. Nor was the lake quiet; it made burping sounds, now and then.

“The lake is farting,” one of the sailors joked.

Philip saw a tree limb sticking out of the tar, and tried pulling it out. It resisted at first, then emerged, a ribbon of black taffy connecting it to the lake, like a baby’s umbilical cord. Philip studied it for a moment, then threw down the stick. He walked over to David.

“You know what this place reminds me of?” asked Philip. “The

Welt-Tier

.”

David puzzled over the word for a moment. “German? World-animal?”

“Yes, that’s right. It was in a science fiction story by Philip José Farmer. The ground was springy, like this lake. When someone walked across it, it rose up, like a wave, and tried to swallow him. The land was really the skin of the Beast.”

The sailors within hearing stirred uneasily. “Philip,” commanded David, “you should be shoveling.” Philip nodded, and took the shovel that was handed to him.

* * *

By the day’s end, they had excavated a rectangular pit, some tens of feet long, and several feet deep. David decided against camping on land, it being Spanish territory, and everyone returned to the ship.

When they came back to the lake to continue their labors, they discovered that the pit had partially filled in. Moreover, some of the nearby “islands” of vegetation had moved during the night.

“The lake does act like a living thing,” David whispered to Philip, “but an exceedingly sluggish one. Not like your

Welt-Tier

.”

Philip stuck a stick into the tar, and pulled it out slowly. The lake made a smacking sound as it released it. “According to Maria’s research notes, tar is usually what’s left behind when oil escapes to the surface, and dries out. But for those islands to move, there must be some liquid circulating beneath the surface. Perhaps it’s just water, but I think it might well be oil.”

“So?”

“We might want to drill for oil nearby. Tar is fine for waterproofing, and roadbuilding, and making organic chemicals, but oil—the liquid form—contains the fuel we need for our APVs. Or for power plants.”

David shrugged. “Perhaps some day we may. But I don’t see the Spanish letting any foreigners, least of all a pack of Protestants, live here without a fight.”

As if David’s words were a signal, they heard a whistling sound, and a moment later, an arrow seemed to sprout out of the tar some distance in front of them. The sailors dropped into their trench, which was the only nearby cover.

“Keep your heads low; see if you can spot them.” As David spoke, a second arrow plunged into the lake to their left, and was quickly swallowed up. Some seconds later, it was followed by a third arrow, better aimed, which nonetheless fell short of their position.

David mentally retraced their trajectories. He realized that they had most likely come from the vicinity of one of the grassy patches he had noticed earlier. He looked for one, along the estimated path, with bushes or trees for cover. Yes, that one, he was sure of it. It was much too far away for the attacker to have expected to hit anything. They were being warned off, he concluded. Probably, given the rate and direction of fire, by a single Indian. But it was possible that a second Indian was already running for help.

“Joris,” he said, “I want only you to fire.” Joris nodded; he was the best shot in the party. David pointed out the shooter’s putative refuge. “Our target is there, I believe. Give him something to think about.

“The rest of you, let’s gather up our tar and head for the ship. Where there’s one Indian, there are probably more close by, and they probably have sent a messenger to the garrison at Puerto de los Hispanioles by now.”

The men collected their tools and put them in the empty wheelbarrows. They headed slowly back to the ship, with the rear guard, led by Joris, making sure that the Indian, or Indians, didn’t get close enough to be a real threat.

“Arwaca Indians,” David told Philip. “When I was in the Caribbean last year, I was told that the Trinidados brought them in some years ago. The native Indians had allied themselves with Sir Walter Raleigh, so, after he left . . .” David drew his finger across his throat.

Snick.

* * *

The

Walvis

, with eighteen guns, was accompanied by another fluyt, the fourteen-gun

Koninck David

, and a yacht, the

Hoop

. They passed through the sometimes treacherous Dragon’s Mouth, between Trinidad and the peninsula of Paria, without incident. Another day’s sailing brought them amidst the islands the up-time maps called “Los Testigos.” Dunes several hundred feet high towered over aquamarine waters, and marine iguanas left footprints and tail tracks as they scurried to and fro.

Some didn’t scurry quickly enough.

“Tastes like chicken,” David pronounced, and his fellow captains, who had joined him for dinner, agreed.

“Anything to report?” he asked.

“My crew is grumbling,” said Jakob Schooneman, the skipper of the

Koninck David.

“It’s been more than six months since the Battle of Dunkirk, and we’ve done nothing to hurt the Spanish. Or to punish the English and French for their treachery.”

“It’s not as though we haven’t been looking for prizes.”

“I know, Captain de Vries. But the mood is turning fouler and fouler. We should have sacked Puerto de los Hispanioles, or San José de Oruña, back on Trinidad.”

“And where would the profit have been in that? All they have is tobacco, and we had plenty of that from Captain Marshall. So why take the risk?”

Captain Marinus Vijch of the yacht

Hoop

, cleared his throat. “The men weren’t that keen on your letting the English stay upriver, either.”

“I know. But we’re weakened by Dunkirk and we can’t afford to fight everyone. The Spanish are the real enemy and we have to focus on them.”

“So let’s find a Spanish town to raid,” said Schooneman.

Vijch nodded. “Portobello,” he suggested.

Schooneman protested. “Too tough a nut to crack, for a force our size.”

“We could probably find some more Dutch ships by one of the salt flats along the way, recruit them.”

“Rely, for an operation like that, on captains and crews you don’t know?”

“Perhaps Trujillo,” mused David. “We have to go to Nicaragua for rubber, and then from there the currents carry us up the coast anyway.”

Schooneman smiled. “The gold and silver of Tegucigalpa is shipped down to Trujillo.” He turned his head to look at Marinus. “Might that satisfy you, Captain Vijch?”

* * *

David brought up the sextant, bringing the skyline into view on the clear side of the horizon glass. Smoothly, he edged up the index arm until the early morning sun’s reflection could be seen on the half-silvered side. He gently rocked the sextant, causing the sun’s image to swing to and fro above the horizon. He delicately twisted the fine adjustment until the yellow-white disk, bright even through smoked glass, seemed to just barely graze the edge of the sea. “Mark!”

Philip had been staring at his wristwatch. He announced the time—his watch was set to Grantville Standard Time, which took into account the relocation of the town by the Ring of Fire—to the nearest minute. Comparing the local time to the time at a place of known longitude was critical to the most accurate method of determining a ship’s longitude.

“Write it in the logbook. Solar altitude is—” David squinted at the vernier, and read off the altitude. “Record that, too. Take that and the star shot we did half an hour ago, and calculate our position.”

Philip stifled a groan. He had made the mistake of admitting that he had taken half a year of trigonometry before embarking on his present escapade. The captain had happily decided that Philip could help with the navigational mathematics. That meant many hours studying

Bowditch

. The Company’s

Bowditch

was based on a couple of “attic and basement” editions of Nathaniel Bowditch’s famous

American Practical Navigator

, and they included calculation of longitude both with a chronometer and by the method of lunars.

“Boat, ho!” cried the lookout.

David grabbed his spyglass and took a look. Sure enough, a longboat with a makeshift sail bobbed in the waves, several miles ahead of them. Philip eagerly dropped the

Bowditch

and joined.

“That’s odd,” he muttered.

“What’s odd?” asked Philip. Since David’s cousin, Heyndrick, had been left behind at the new colony in Suriname, Philip had gradually become David’s confidante on the ship. In retrospect, it wasn’t surprising; since Philip wasn’t a sailor, talking to him didn’t create discipline problems. The fact that Philip was one of the mysterious up-timers also gave him a cachet.

“No one would willingly cross the open sea in a longboat. They are used for in-shore work by ship’s crews.

“Still . . . we mustn’t get careless. Many a pirate has gotten his first ship by stealing a fishing boat and then coming alongside an imprudent merchant vessel.” David gave orders; the crew prepared to repel boarders. The flotilla altered course to bring itself closer to the mysterious small craft.

David hailed them. In English, since it wasn’t prudent to do so in Dutch.

They responded in kind. “Help us, please, we’re the last of the

White Swan

.” David sent his own longboat over to inspect, and his crew reported back that they did indeed seem to be mariners in distress. Not just English, but Dutch as well. David allowed most of his crew to stand down, and the strangers were taken aboard. If David had a few men still armed and ready, well, that was only prudent in Caribbean waters.

The longboat’s crew were brought some food and liquor, and encouraged to tell their tale. Not that they needed much encouragement.

“I am—was, I should say—the carpenter of the White Swan, out of Plymouth. There were two Dutch fluyts with us, all peacefully gathering salt from the pans of Bonaire.” That was one of three islands off the coast of Venezuela. “We were sent in the longboat to Goto Meer, a lake in the northern part of the island, to fetch fresh water. We were making our way back when we saw the attack. A squadron of six Spanish warships came through, and immediately attacked the two Hollanders.

“The

White Swan

kept its distance. I suppose the captain, God rest his soul, must have figured the Spanish were just after the Dutch. We should’ve known better. Once both Dutch ships were safely in Duppy Jonah’s Locker, the Spaniards came after the

White Swan

. And sent her down as well.”

“So much for peace,” said another English sailor.

“‘No peace beyond the line,’” David quoted. “And the Spanish think they and the Portuguese own all of the New World.”

The carpenter nodded. “We stayed hidden among the mangroves—what else could we do?—until the Spanish moved west, and the sun went down. There was a moon, so we went looking for survivors, and hauled in these Dutchmen, poor wretches. They had found something to cling to, but they were still pretty waterlogged when we took them on.” The Dutch survivors were still too weak to make conversation, but they nodded feebly.

“And a good thing for you that you did,” David said. “Since I am Dutch, and we are under Swedish colors. Otherwise, we might be less charitable, considering how the English treated the Dutch at the Battle of Dunkirk.”

* * *

The English wanted to be taken to Saint Kitts, but that was well off David’s course, and thus out of the question even if David were sure of a friendly reception. And the American colonies were English no longer. David told his unexpected guests that he could drop them off on Providence Island, off the coast of Nicaragua. There was a Puritan colony there. They would work as crew, in the meantime, of course.

Providence Island was only a few miles north of the route that David had planned originally. However, there was a very good chance that, on that path, they would overtake the punitive Spanish squadron, which was probably en route to Cartagena or Portobello, and more or less hugging the coast. David decided to head deeper into the Caribbean Sea before turning southwest toward Providence. Thanks to the sextant and the wristwatch, he didn’t have to limit himself to latitude and coastal sailing. Wind permitting, of course.