1493: Uncovering the New World Columbus Created (52 page)

Read 1493: Uncovering the New World Columbus Created Online

Authors: Charles C. Mann

Tags: #Americas (North; Central; South; West Indies), #Expeditions & Discoveries, #United States, #Colonial Period (1600-1775), #History

As a captive, Motecuhzoma had asked Cortés to protect his family. This was a big job: the emperor had nineteen children. The conquistador failed—smallpox and war killed all but three of the nineteen. One of the survivors was Tecuichpotzin. (The Spaniards gave her a European name that they could pronounce: Isabel.) Tecuichpotzin was the daughter of the emperor’s principal wife, whereas the other two surviving children were from wives of lesser value. All were then adolescents. Tecuichpotzin, twice a widow, was about twelve.

Cortés regarded them as the legitimate rulers of the Triple Alliance, Tecuichpotzin the most important. The conqueror’s task, as he saw it, was to graft Spanish authority onto native roots. Europeans would rule through Indian institutions. To do this, he made the straight-faced claim that while held hostage Motecuhzoma had voluntarily given sovereignty over the Alliance to Carlos V. Because Indian elites therefore were now good Spanish subjects, they had to be treated as equivalent to Spanish elites. The two groups would have to mingle on equal terms. Cortés gently nudged this accommodation forward by impregnating Tecuichpotzin.

He didn’t do this immediately—she was still married to Cuauhtemoc. Claiming that the Triple Alliance leader was plotting against Spain, Cortés executed him in 1525. He then arranged for Tecuichpotzin to marry her fourth husband, a conquistador he regarded with especial fondness. This man died a few months later. Cortés considerately moved the widow, now sixteen or seventeen, into his own spacious home, which is where she became pregnant, and where he arranged for her fifth marriage, to another favored conquistador. Leonor Cortés Moctezuma was born in 1528, four or five months after the wedding.

3

Leonor was not the conqueror’s only illegitimate child—he had at least four others. Nor was she his only half-Indian child. Throughout the assault on the Triple Alliance, Cortés traveled with a guide and interpreter: a woman whose name has come down to the present as, variously, Malinche, Marina, or Malintzin. Born to a noble family in a neutral zone between the Triple Alliance and the Maya, she was sold to the Maya after she became an impediment to her stepfather’s family. Because Malinche had learned the language of the Triple Alliance as a child, the Maya gave her to Cortés, who was bound in that direction. A sexual relationship began quickly. The conqueror’s son Martín came into the world in May or June 1522, which means he was conceived in August or September, in the celebratory aftermath of the empire’s fall. (Another half-native daughter, María, is referred to in Cortés’s will, but nothing else is known about her except that her mother, too, was one of Motecuhzoma’s daughters. One assumes María was conceived during the months when Cortés held Motecuhzoma hostage and that her mother died in the war.)

Cortés did not hide his illegitimate, hybrid children. Leonor was raised by her father’s cousin, the administrator of his vast estate. Sugar profits provided a dowry big enough for her to attract the hand of Juan de Tolosa, discoverer of Mexico’s biggest silver mine. Cortés took more dramatic action for Martín: he sent the boy to the Spanish court to serve as a page and hired a Roman lawyer to petition Pope Clement VII to legitimize him. The pope, born as Giulio de’ Medici, had every reason to sympathize. Not only was he himself illegitimate, he had his own illegitimate, hybrid child—Alessandro de’ Medici, whose mother was a freed African slave—and had tried to ensure his future by appointing him duke of Florence. The pope did indeed legitimize Martín Cortés. Along with Cortés’s oldest legitimate son, also named Martín Cortés, he was a principal heir in the conqueror’s will. Both were full members of Spanish society—and proved it by spending five years in a court battle over their bequests from their father. Naturally, they fought over Indian slaves.

Europeans and Indians had been mixing since Colón touched down at Hispaniola. Most of the colonists on the island were young, single men; in a census of Hispaniola in 1514, only a third of its

encomenderos

were married. Of these, a third were married to Taino women. Fernando and Isabel encouraged such intercultural coupling, though they believed it should lead to Christian marriage. Christian marriage, perhaps surprisingly, was also the goal of some natives: by marrying their daughters to Spaniards in a Christian ceremony, elite Indians could reinforce their status. For many Spaniards, though, a Taino ceremony was more useful than a Christian wedding—only through marrying a native woman could a low-ranking Spaniard gain access to the goods and workers controlled by high-status Indians. As a result, many of the Spaniards whom the clergy viewed as living in sin thought of themselves as married.

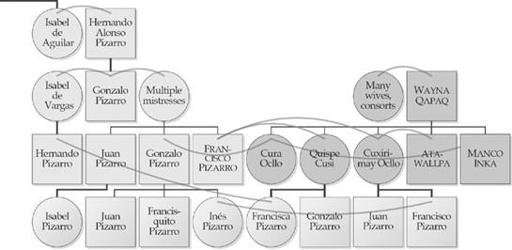

A hybrid society was coming into existence, first in the Caribbean, then everywhere else in the Americas. The mixing began at the top—Cortés was an example. Like many members of the first generation of conquistadors, Cortés came from Extremadura, a poor, mountainous area controlled by powerful families who had been marrying into each other for generations. His distant cousin was Francisco Pizarro, conqueror of the Inka empire—Pizarro’s great-uncle was married to Cortés’s aunt. When the intertwined conquistador families married into the equally intertwined families of noble native societies, they produced the kind of baroque, multibranched family trees that wake up genealogists at 3:00 a.m.—Cortés’s relations with the Mexica (Tenochtitlan’s people) were prototypical.

Cortés was only the beginning. Like his Extremaduran cousin, Pizarro set up shop with a noble native woman: Quispe Cusi, the sister or half sister of Atawallpa, the Inka emperor whom Pizarro overthrew. Quispe Cusi bore Pizarro two children, Francisca and Gonzalo, whom he asked the king to legitimize by royal decree. Pizarro often said that Quispe Cusi was his wife, but he didn’t actually marry her. Nor did he let this “marriage” interfere with his liaisons with two other royal Inka sisters, one of whom bore him another two children. An illegitimate child himself, Pizarro did not turn his back on his half-Inka offspring. Francisca, his daughter by Quispe Cusi, became his principal heir. (Her brother Gonzalo died at the age of nine.)

A

MERICAN

I

MPERIAL

F

AMILIES OF THE

15

TH

AND

16

TH

C

ENTURY

To bolster the legitimacy of their rule, conquistadors often married into or took consorts from the elite of the peoples they conquered, Cortés and Pizarro being among the leading examples. They created a generation of mixed-culture children who became some of the new colonies’ most powerful citizens. Because many of the conquistadors were from Extremadura, a mountainous region dominated by a few interrelated families, they were often as tightly related as Indian nobility. The result was a multicultural family web unlike any other.

Click

here

to view a larger image of this entire chart.

The conqueror came to Peru with three brothers. One took an Inka princess as a mistress. Another took an actual Inka queen—he stole the wife of the puppet emperor whom Francisco Pizarro had installed after killing Atawallpa. The remaining Pizarro brother, Hernando, was the only one to return to Spain alive. The wary Carlos V put him under house arrest—Hernando, after all, had a history of impulsively overthrowing kings. Besides, he had murdered a lot of Spaniards in battles over the spoils of Peru. When the king died, his successor, Felipe (Philip) II, continued the imprisonment. Altogether Hernando was confined for twenty-one years. “His confinement was gentle enough,” John Hemming observed in

The Conquest of the Incas

(1970), his marvelous account of the Pizarro brothers’ assault on Peru. “He was in the same prison and apartments that had harbored [French] King Francis I after his capture [in a battle with Spain] in 1525.” Rising at noon, Hernando ate and drank lavishly in his sumptuous quarters, then entertained Spain’s elite far into the night. He had a mistress who bore him a daughter in prison.

Hernando met Francisca for the first time since infancy when she was seventeen and had just inherited her father’s vast fortune. The fifty-year-old Pizarro married her almost on the spot, Hemming wrote, “unperturbed by consanguinity, the thirty-three-year difference in age, or his own imprisonment.” When Hernando was at last released from house arrest, the couple built a massive Renaissance-style palace on the main plaza of Trujillo, the city where the Pizarros had been born. In a kind of colonial fantasy, they dined on gold plates with Peruvian food and imported a squadron of Inka servants to wait on them.

The Pizarros were wealthier than their fellow conquistadors but in other ways not exceptional. Historians have tracked the lives of ninety-seven of the 150 men who founded Santiago, Chile, in 1541. They had 392 children and grandchildren, of whom 226 (57 percent) were of Indian descent. One conquistador in Chile proudly told the Inquisition in 1569 he had produced fifty children with non-European mothers.

4

Few of those children had African blood. That would change—rapidly. As plantation slavery spread, the percentage of Africans in the hemisphere rose, and with it the number of Afro-Indians, Afro-Europeans, and Afro-Euro-Indians. By 1570 there were three times as many Africans as Europeans in Mexico and twice as many people of mixed parentage. (Both were outnumbered by Indians, of course.) Seventy years later there were still three times as many Africans as Europeans—and

twenty-eight

times as many mixed people, most of them free Afro-Europeans.

On the one hand, Spaniards in some ways easily accepted the hybrid world they were making. Europeans then did not have the same concept of “race” as later generations and thus did not see themselves as being different from Africans or Indians on a biological level. They did not fear what today would be called genetic contamination. On the other hand, the blending of native and newcomer led to enormous fear about

moral

contamination.

Spain justified its conquest, one recalls, by promising to convert the Indians. Spaniards’ consistent mistreatment of native people impeded this mission. The Franciscan friars who held sway over New Spain’s religious life proposed an apartheid solution: turning the colony into two “republics,” one for Indians, one for Europeans. Untroubled by European demands, Indians would focus on conversion in all-Indian neighborhoods and towns; Spaniards would focus on growing rich from the fruits of conquest in an all-Spanish setting. Thus in 1538 Bishop Vasco de Quiroga began to group thirty thousand Indians in the mountains west of Mexico City into reservation towns that he intended to make into an American utopia—literally, for Quiroga laid out the settlements according to the prescription in Thomas More’s novel

Utopia,

which had been published twenty-one years before.

The cultural and ethnic jumble in the streets of Spain’s American colonies was often reflected in its art—as in this anonymous eighteenth-century oil, which depicts the Virgin Mary embedded in the great silver mountain of Potosí, visually uniting Christianity with the Andean tradition that mountains are the embodiment of a deity. (

Photo credit 8.4

)