The History of the Medieval World: From the Conversion of Constantine to the First Crusade (47 page)

Authors: Susan Wise Bauer

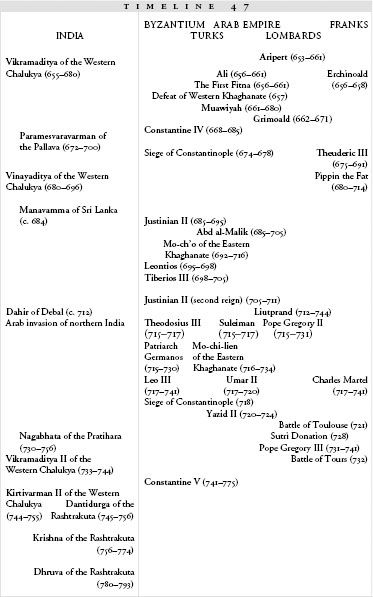

Between 718 and 741, the caliph tries to follow Muhammad’s teachings exactly, while the emperor of Byzantium destroys icons and the pope is given a kingdom of his own

A

FTER THE FAILED SIEGE

of Constantinople in 718, the caliph Umar II led the Umayyad empire into its first reform. The empire was less than a century old, but already the tensions that ribbed it were stretching to breaking point.

Around the same time as the siege of Constantinople, Umar II had noticed a troubling problem in the empire’s administration. Muhammad, long before, had instituted a “head tax,” ordering Christians and Jews within Muslim communities to pay a fee in return for accepting the protection of the Muslim state. Theoretically, converts to Islam were at once freed from the obligation to pay the head tax. But the caliphs after Muhammad, administering a burgeoning empire that Muhammad had probably never envisioned, were reluctant to give up such a lucrative tax. More and more often, local officials “forgot” to exempt new converts from the head tax, and they simply went on paying it.

As a result, almost all non-Arab Muslims in the empire were currently sending the head tax to Damascus. This struck Umar II, who was a back-to-the-exact-prescriptions-of-the-Prophet radical, as corrupt. He declared that all Muslims, no matter their race or length of commitment to Islam, should be exempt from the tax.

This made him immensely popular, but it ruined the empire’s tax base—particularly since huge numbers of conquered peoples suddenly converted en masse to avoid the tax. However, Umar II didn’t have to deal with the consequences of his reforms. He died a natural death in 720, and his successor Yazid II immediately reimposed the tax before the empire went broke.

1

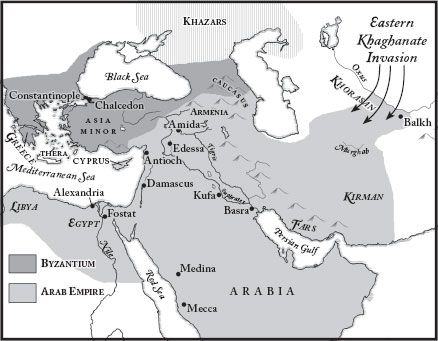

At this, Yazid II’s popularity plummeted, and the biggest crowd of recent converts—the non-Arab tribes in Khorasan—rebelled. Not only did they rebel; they also sent a message to the khagan of the rebuilt Eastern Khaghanate, Mo-ch’o’s nephew and successor, Mo-chi-lien, asking him for aid. Mo-chi-lien had followed up on his uncle’s conquests by pushing the Turkish kingdom towards the Arab border, swallowing the land once belonging to the Western Khaghanate and re-establishing a unified Turkish empire. Pleased at an excuse to push farther southwest, he sent his troops towards the Oxus, and a ten-year struggle between the Turkish and Islamic armies in Khorasan began.

2

47.1: Struggle in Khorasan

With the Arab armies occupied elsewhere, the emperor Leo III took the opportunity to do some doctrinal house-cleaning of his own. He issued a command that all Jews in his empire be baptized as Christians; a few were, but many more fled, some into Arabic lands, others up north into the lands of the Khazars. And he began to campaign against a practice that had long disturbed him: the use of icons in Christian devotion.

Constantinople was home to scores of icons—paintings of saints, or of the Virgin Mary, or of Christ himself. An icon (the Greek word

eikon

meant “image” or “likeness”) was more than a symbol and less than an idol: an icon was a window into the sacred, a threshold at which a worshipper could stand and come that much closer to the divine.

Christians had been using icons as an aid to prayer and meditation for centuries, but a counter-thread of unease with these images had been stitched into Christianity from its beginnings. In the earliest years of apostolic teaching, Christians had been distinguished from followers of the old Roman religion primarily because they refused to worship images, and for the second-and third-century theologians the use of icons veered perilously close to idolatry.

Once the ancient Roman customs had died out, so did the risk that Christians would be drawn back into them, and the use of icons became much less fraught with danger. But a strong subset of Christian theologians continued to oppose the use of icons, not because of the danger of idolatry, but because painting an image of Christ suggested that the son of God was characterized by his human nature, not his divinity. God, Who was Spirit, could not be pictured; if Christ

could

be, didn’t that imply that he was not truly God? Couldn’t it be argued that an image of Christ “separates the flesh from the Godhead” and gives it a separate existence? Arguments over the use of icons became a subset of the arguments over the exact nature of Christ as God-man—arguments that had been going on for centuries, despite a whole series of church councils making declarations intended to settle the matter once and for all.

3

Leo III had a less subtle concern: he was disturbed by the tendency of his subjects to treat icons as though they were magic. During the siege of Constantinople, the patriarch Germanos had taken the most venerated icon in Constantinople, a portrait of Mary that was rumored to have been painted by the gospel-writer Luke himself, and had paraded around the walls with it.

4

When the siege lifted, far too many of the citizens of Constantinople chalked the victory up to the icon (called the Hodegetria), as though it had been a sorcerer’s wand waved over the enemy. This sort of thinking had no place in Christianity.

Perhaps Leo III also felt some justifiable indignation in seeing the praise for his hard-won triumph given to the icon. Still, his actions over the next years, which nearly lost him the throne, are those of a man acting against his own best interests, something explained only by deep conviction.

5

In 726, Leo decided to begin to wean the people away from their magical thinking. According to Theophanes the Confessor he was finally moved to action by a serious eruption of the volcano on Thera: “The whole face of the sea was full of floating lumps of pumice,” Theophanes writes, “[and] Leo deduced that God was angry at him.” As a first tentative act against the icons, he sent a band of soldiers to take down the icon of Christ that hung over the Bronze Gate, one of the main entrances to the palace.

6

His fears about the overreliance of the people on the icons were immediately justified. A mob gathered to find out what was happening, and when the icon began to come down they rioted and attacked the soldiers. At least one soldier was killed. Leo retaliated with arrests, floggings, and fines. With amazing rapidity, the conflict spread into the more distant regions of the empire. The army in the administrative theme of Hellas (Greece) rebelled and set up their own emperor, declaring that they could not follow a man who attacked the holy icons.

The rebellion was short-lived and the new emperor was captured and beheaded, but feelings continued to run high. In every great city across the empire, iconoclasts (icon-smashers) and iconodules (“icon-slaves,” meaning icon-lovers) argued, while in Constantinople Leo III preached against “idol-worship.” Iconoclastic bishops removed icons from their churches, while iconodules wrote long treatises defending their use: “The memory of Him who became visible in the flesh is burned into my soul,” wrote the monk John of Damascus. “Either refuse to worship any matter, or stop your innovations.”

7

For an icon-lover, the philosophical problem underlying iconoclasm was its suspicion of matter, its willingness to relegate Christianity entirely to the spiritual realm and to separate off earthly existence as fundamentally flawed. And, like all theological debates, the use of icons had a political edge: iconodules also accused Leo III of having too much sympathy for Muslims, who refused to make images of living things. He was, sniped the icon-loving Theophanes, too much shaped by “his teachers the Arabs.”

8

To the west, Pope Gregory II waxed indignant. He was himself a supporter of icons, but more central than the issue of icons was Leo III’s willingness to make theological pronouncements. The pope sent a sharp message rejecting Leo’s pronouncements. “The whole West…relies on us and on St. Peter, the Prince of the Apostles, whose image you wish to destroy,” he wrote. “You have no right to issue dogmatic constitutions, you have not the right mind for dogmas; your mind is too coarse and martial.”

9

More seriously for Leo, the pope ordered his own flock to ignore the imperial commands to destroy icons. By this time, only a handful of cities in Italy still maintained any loyalty to the Byzantine emperor: among them were the southern city of Naples, the port village of Venice on the northern Adriatic coast, Rome, and Ravenna, where the exarch still lived. Much of the rest of Italy was ruled by the Lombard king Liutprand. Pope Gregory II’s condemnation meant that the peoples in these territories now had a theological justification for finally deserting Constantinople.

10

The Italian cities had been feeling the pinch of higher and higher imperial taxes for some time, and their populations welcomed the justification. The duke of Naples actually tried to carry out the emperor’s command to destroy the city’s icons and was killed by an indignant mob. In Ravenna, the exarch was killed by his own subjects. And in Rome, the pope was acting with increasing disregard for the imperial stamp of approval.

King Liutprand of the Lombards saw the opportunity to extend his own power at the expense of the emperor’s. He attacked Ravenna and took away the port, although the residents of the city put up resistance and Liutprand was unable to penetrate the marsh; Ravenna was now no-man’s land, unable to communicate with Constantinople, and no longer under an exarch. The pope made no objection to this; he had decided to see Liutprand and the Lombards as co-belligerents in the fight against the emperor’s tyranny, and Liutprand was willing to foster this opinion.

The growing alliance between the two men was strengthened when a new exarch appointed by Leo III came from Constantinople. This exarch, a man named Eutychius, landed at Naples (the Ravenna port was now inaccessible) and sent a series of gifts and money bribes to Liutprand, promising more if the Lombard king would help him to assassinate the pope.

11

Liutprand refused. Instead, he went south to Rome and took control of Byzantine territory nearby: the city of Sutri and the land surrounding it. In 728, he offered to turn the territory over to the control of the church—a “gift” that became known as the Sutri Donation. It was not, in fact, a donation; Pope Gregory II handed over an enormous payment from the church treasury in exchange. But everyone benefitted. Liutprand got back a good deal of the money he had spent attacking Ravenna, and the pope now had, for the first time, a little kingdom of his own. It was the first extension of papal rule outside the walls of Rome: the first of the Papal States.

12

Map 47.2: The First Papal State

Undeterred by his critics or by his troubles in Italy, in January of 730 the emperor Leo III issued a formal edict ordering the destruction of icons all across the empire. When the patriarch Germanos refused to support the edict, Leo deposed him and appointed a replacement.

13

Pope Gregory II died not long afterwards, and his successor, Pope Gregory III, called a church council, which met in 731 and excommunicated all the icon-destroyers. Leo III, in return, announced that the handful of Byzantine possessions left in Italy were no longer subject to the authority of the pope; instead, they fell within the realm of the patriarch. The eastern and western branches of the church had drawn that much farther apart.

Leo III died in 741, leaving behind a legacy of lost lands, shattered icons, and displaced peoples. But the empire was no better off after his death; he was succeeded by his son Constantine V, twenty-three and energetic, and even more rabidly iconoclastic than his father.