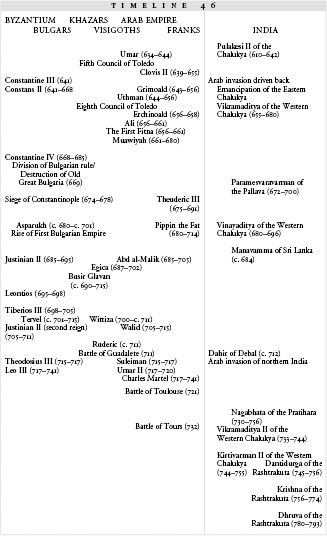

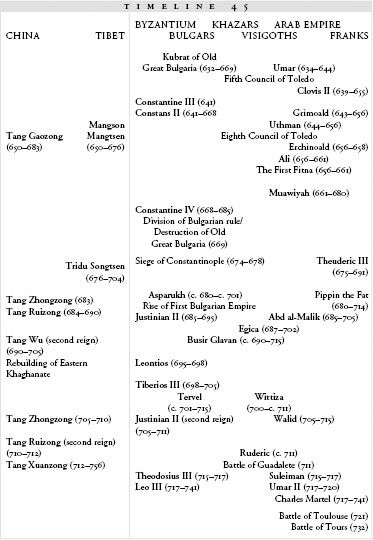

The History of the Medieval World: From the Conversion of Constantine to the First Crusade (46 page)

Authors: Susan Wise Bauer

The do-nothing Merovingian kings had been dominated for forty years by a succession of ambitious mayors of the palaces. In 680, the Austrasian nobles had chosen a Frankish official named Pippin the Fat to occupy their palace; he was the grandson of Pippin the Elder, the mayor who had first tried to make the office hereditary back in 643. At his election, the throne of Austrasia was empty; its last do-nothing king had just died. Pippin the Fat (later known as Pippin the Middle, since his grandson would also be named Pippin) refused to support a new candidate for the Austrasian crown. None of the Frankish nobles insisted, and Pippin the Fat ruled as de facto king of Austrasia.

This did not please the Merovingian king who sat on the throne of Neustria, Theuderic III (he happened to be the youngest son of Clovis II and had been retrieved from his monastery to ascend the throne after both of his brothers died). In 687, Theuderic III attacked Austrasia, but Pippin the Fat’s army defeated the king so thoroughly that Theuderic had to agree to make Pippin the Fat the joint mayor of all three palaces: Austrasia, Neustria, and Burgundy.

After this, Pippin the Fat had begun to call himself

dux et princeps Francorum

, “Duke and Prince of the Franks.” He was neither a king nor a servant of the king; he had returned to an older Germanic description of his power, calling himself the principal leader (

princeps

) among many leaders (

duces

, dukes). He ruled in Austrasia as

dux et princeps

for nearly thirty years, outliving various puppet-kings of the Merovingian family,

*

and died in 714, at age eighty, just as the Arab armies were storming towards the Frankish border.

This was bad timing. The various royal cousins who wore the Frankish crowns were not powerful enough to spearhead any effective defense, and Pippin’s death left the mayoral offices empty as well. Both of his legitimate sons, born to his wife Plectrude, had died before him. He did have two illegitimate sons, the children of his mistress Alpaida; but Plectrude hated both Alpaida and her sons and did not want them inheriting Pippin’s power.

Instead, she insisted that the real heirs to the office of mayor of the palace should be her grandsons, the children of her dead sons. To make sure that Alpaida’s sons wouldn’t get power, she nabbed the older and most ambitious son, Charles Martel, and imprisoned him in Cologne.

Charles escaped from prison almost at once and returned to Neustria, where he had to fight Plectrude (acting as regent for her young grandsons) and various claimants to the office of mayor of the palace. The civil war lasted for two years, but by 717, Charles Martel had made himself mayor of the palace of Austrasia and had put a royal cousin on the throne as a do-nothing king.

He had control, although it was shaky, over most of the Frankish lands. But to the south, a local nobleman named Odo, who had the hereditary right to govern the region known as Aquitaine, had taken the opportunity of the civil war to make himself more or less independent. He was supposed to be loyal to the Franks, but he reserved his loyalty for the do-nothing king; he was suspicious of Charles Martel’s ambitions and kept himself aloof from any alliance with the mayor of the palace.

As a result, when the Arab armies appeared on his southern border, Odo of Aquitaine had no powerful friends to come and help him. On June 9, 721, the tiny army of Aquitaine—reinforced by only a few resistance fighters from the mountains of Asturias—met the Arab armies at the Battle of Toulouse, under Odo’s command.

With staggering self-absorption, the Frankish chronicles make almost no mention of this battle. They are preoccupied with Charles Martel’s rise to power; Odo of Aquitaine appears in them only as Charles Martel’s enemy, not as the savior of the Franks. But Odo defeated the Arabs at the Battle of Toulouse, killing the governor of al-Andalus in the fighting, and halted the Arab advance into Europe. It was one of the worst (and most unexpected) defeats suffered by an advancing Islamic army. “He threw the Saracens out of Aquitaine,” the chronicles remark, laconically, and in doing so he preserved the culture of the Franks.

13

The dead governor of al-Andalus was replaced by a new appointee, the military man al-Ghafiqi, and for a time the Arabs retreated from the Frankish border. Al-Ghafiqi spent eight or so years governing al-Andalus before leading an army back towards the northeast in 732.

Once again Odo of Aquitaine came out to meet the Arab attack. This time, Odo was horribly defeated at the Battle of the River Garonne. He was forced back into Aquitaine, and the Arab armies crossed the river, coming first to Bordeaux, then to Poitiers. According to the chronicle of Fredegar, they burned churches and slaughtered the population as they went.

14

Odo, in desperation, sent to Charles Martel, offering to swear his loyalty if Charles would come and help. Up until this point, it seems, the Franks had not fully appreciated the danger of the Arab advance. But the previous decade had opened their eyes, and Charles Martel marched south at once, making Odo one of his commanders and giving him authority over the Aquitaine wing of the army.

The Arabs under al-Ghafiqi and the Franks under Charles Martel met near Poitiers in October. The battles that followed went on for more than a week, with no clear advantage emerging.

Days into the fighting, al-Ghafiqi was killed. At his fall, the Arab forces began to retreat, and Charles Martel followed them. The chronicle of Fredegar, which is relentlessly pro-Charles (and anti-Odo), announces that Martel pursued the Arabs in retreat to grind them small, utterly destroy them, and scatter them like stubble. This is not exactly true. They had lost the battle, but they were not entirely defeated; they burned and looted their way back into al-Andalus, more or less unhindered, while Martel came along behind.

15

The battle at Poitiers in 732, immortalized by Frankish historians as the Battle of Tours, did turn the Arab advance back; the Muslim empire halted at the border of Aquitaine and did not again press forward. Charles Martel’s victory had been competent and well planned. But his nickname “The Hammer”—given to him because he hammered away at his enemies and ground them to dust—was not completely deserved. Odo of Aquitaine, now reduced to paying homage to the mayor of the palace, had orchestrated the triumph. But Charles Martel had better court historians.

Between 712 and 780, the Arab armies establish a province in the Sindh, and the southern Rashtrakuta build a reflection of the sacred north

T

HE

A

RAB ARMIES

, blocked at Constantinople and at Poitiers, had better fortune at the Indus.

The conquest of the Sindh, begun back in 643, had halted when the caliph Umar realized how desolate the area was. Now al-Hajjaj, the governor of the eastern reaches of the Islamic empire, recalled his son-in-law Muhammad bin Qasim from his military post in Fars and sent him back towards the Indus to finish the job. Bin Qasim’s first target was the port city of Debal, right on the eastern edge of the Makran desert.

At this time, the port seems to have been under the control of a tribal leader named Dahir, who probably ruled not only his own tribe but a few surrounding tribes as well. We know of him from the Arabic history

Tarikh-i Hind wa Sindh

, written sometime after the eighth century and translated from Arabic into Persian in the early thirteenth century. According to the anonymous author, when bin Qasim marched towards Debal in 712, Dahir had just inherited control of the port from his father. He was not a very important ruler, but he stood as a barrier between the Arabs in Makran and the lands farther east.

1

Rather than simply attacking him, al-Hajjaj and bin Qasim manufactured an excuse for their aggression. Pirates had attacked Arab ships setting off from the coast of the Makran, and al-Hajjaj insisted that Dahir punish the sea raiders. Dahir, receiving this message, retorted that he had no authority over the pirates, which was undoubtedly true; he was not nearly as powerful as the Arabs seemed to think. But al-Hajjaj took Dahir’s response as hostile and authorized his son-in-law’s attack. The two men were searching for reasons to invade—which suggests that the invasion of India may have been undertaken without the complete sanction of the caliph in Damascus.

Muhammad bin Qasim approached Debal by land, while further reinforcements and siege engines arrived by sea. Al-Hajjaj supervised the offensive by letter;

Tarikh-i Hind

says that he wrote every three days with instructions, which is as close to micromanaging as he could get, given the difficulties of eighth-century travel.

After an extensive siege, Debal was taken. Dahir, seeing that the city was lost, withdrew with most of his men, and bin Qasim slaughtered the remaining defenders. He ordered a mosque to be built in Debal, left a garrison at the port, and kept marching eastward.

Dahir fled to the other side of the Indus, abandoning the lands between the port and the river (all the villages surrendered to bin Qasim as he approached). He did not believe, the Arab historian tells us, that bin Qasim would attempt to cross the river, but bin Qasim ordered a pontoon bridge (boats roped together to form a wavering wooden path) laid across the Indus, stationing a boat full of archers at the head of the bridge and thrusting it forward a little farther as each boat was added behind. The archers kept Dahir’s men at bay until the line of boats reached the far shore.

2

Bin Qasim then marched his men across the fragile bridge. “A dreadful conflict ensued,” the historian writes, with Dahir and his soldiers mounted on elephants, and the Arab soldiers shooting flaming arrows into the howdahs—the reinforced carriages on the elephants’ backs. Towards evening, Dahir was knocked from his elephant by a well-placed arrow. An axman on the ground beheaded him.

3

His men retreated upriver and fortified themselves at the city of Brahmanabad, well to the northeast. But over the next three years, bin Qasim conquered a swath of land across the Indus that included Brahmanabad, which he made into his capital. The new Indian province proved to be a treasure trove for the eastern part of the empire; the tribes in the conquered land paid regular and expensive tribute to the occupiers. The ninth-century Persian historian al-Baladhuri writes that when the governor al-Hajjaj reckoned up the tribute paid during the first year, his profit was double the cost of the conquest.

4

T

HE NORTHERN

I

NDIAN LANDS

were perpetually troubled by outsiders coming east across the Indus or south across the mountains. But a kind of cyclical, indigenous battling, almost completely unaffected by outside forces, had characterized the south of India for centuries. The kingdoms of the south breathed, their borders expanding and contracting, each dynasty hanging on to power but seeing the extent of that power change almost yearly.

In the eighth century, the Western Chalukya expanded again, dominating the south central plain under its king Vikramaditya II. This was nothing new; Vikramaditya’s conquests simply pushed the kingdom back to the same borders ruled by Pulakesi II a century earlier. But in 745, a new southern kingdom did arise; and its king not only travelled far enough north to encounter the outside invaders, but also tried to reproduce the northern geography in the south.

46.1: Indian Kingdoms of the Eighth Century

His name was Dantidurga, and in 745 he inherited the rule of his southern tribe. His father had kidnapped his mother, a noblewoman of Chalukya birth, and married her by force; so Dantidurga had Chalukya blood in his veins, however unwillingly. With it had apparently come the compulsion for conquest. He started out by fighting his neighbors, with growing success. Sometime around 753, he decided that he was strong enough to take on Kirtivarman II, son and heir of the Western Chalukya king Vikramaditya. A poem records the outcome of the battle during which Dantidurga apparently triumphed despite his much smaller forces:

Assisted by only a few

As if by a bend of his eyebrow

He did subdue

That tireless emperor [Kirtivarman II]

Whose weapons were of undimmed edge.

5

Kirtivarman II kept only a small remnant of his father’s domain; Dantidurga claimed the rest and annexed it to his own territory.

Immediately afterwards, Dantidurga pushed his way north across the Narmada. Kirtivarman II had been his greatest enemy in the south; in the north, his natural target was the tribal chief of the Pratihara, who ruled a territory that surrounded the city of Mandore and stretched all the way up into the Sindh.

An outlying Arab force met Dantidurga as soon as he crossed over into the Sindh, but he drove them back and made his way straight for Mandore. In 754, he managed to reach the city and occupy it, forcing the Pratihari king Nagabhata to surrender.

But there was no conquest of the north. Dantidurga apparently did not have the men, or the bureaucracy, to rule a far-flung empire. He took tribute from Nagabhata and went back south. As soon as he got back on the southern side of the Narmada, Nagabhata came after him and recaptured all the northern territory.

What Dantidurga’s next move might have been will never be known. He died, like Alexander the Great, at the age of thirty-two, only two years later. But he had pencilled in the borders of the next great Indian power: the kingdom of the Rashtrakuta.

6

He had come to the head of his tribe young, and his ceaseless campaigning had apparently left him no time for wife or children; he was succeeded as tribal leader and king by his uncle Krishna I. Krishna I went to work filling in the outlines with nearly eighteen years of unceasing warfare. His greatest accomplishment was to bring down the Western Chalukya king and seize the remaining Western Chalukya lands for his own.

Krishna never ventured as far north as his nephew, but the northern landscape apparently occupied his thoughts. In celebration of his victories, he commissioned a new temple to join the caves at Ellora: this temple, the Kailasa (or Krishnesvara), was carved out of the rock without seams. It was, in the words of one of his inscriptions, “an astounding edifice” that amazed even “the best of the immortals.”

7

More than that, it was a mirror of the north. Kailasa was not just a name; it was the name of the peak in the northern Himalaya where the Ganges river, the source of life, originated. Kailasa was the highest and holiest place in the mountains, the sacred spot from which creation sprang. By building its reflection in the mountains that lined the Narmada river valley, Krishna was proclaiming himself to be the southern equivalent to the ancient, godlike rulers of old, the mythological sovereigns of northern India. He was making the sloping, low Vindhya mountains into “Himalaya-in-the-Deccan,” a new sacred border.

8

After Krishna’s death, his son Dhruva once again invaded the north, something his father had never done. In 786, he seized Mandore, this time for good, and headed even farther north, towards Kannauj.

Kannauj did not fall to him right away. The city lay at a three-way intersection of kingdoms: his own Rashtrakuta realm, reaching up from the south; the Pratihara, whose realm had shifted somewhat north and east and now extended over into the Ganges valley; and the Pala, whose capital was the city of Gaur, closer to the Ganges delta, but who had advanced westward as far as Kannauj.

For the next century, Kannauj would remain at the battlefront between the three crowns. But even without possession of the northern city, Dhruva had managed to bring northern and southern land together under one throne. When he crossed the Ganges, he had made his father’s boast good: the borders of the Rashtrakuta had finally intersected the sacred river.