The History of the Medieval World: From the Conversion of Constantine to the First Crusade (44 page)

Authors: Susan Wise Bauer

Between 683 and 712, the Empress Wu Zetian becomes the Son of Heaven

I

N

683,

THE CRIPPLED EMPEROR

Tang Gaozong hovered at the edge of death, with his devoted empress Wu Zetian at his side. Despite a series of strokes, his mind was still clear. He called his chief minister to the Hall of Audience in the royal palace so that he could make his final choice of an heir known, and give his last instructions for the transfer of power. Later that same night, he died in the Hall, too weak to move to his bedchamber.

1

He had chosen his twenty-seven-year-old son Zhongzong to be the next emperor, and had designated Zhongzong’s two-year-old son Li Chongzhao as “Heir Apparent Grandson”—a highly unusual move, reflecting his own fears that the relatively young Tang dynasty had not yet established itself firmly on the throne. He had also issued a last order: that the new emperor consult Empress Wu whenever “important matters of defense and administration cannot be decided.”

2

He had intended this triple pronouncement to protect Tang power, and it did, although not quite in the way he had intended. With the power to make final decisions enshrined in her husband’s last words, the empress removed her son after barely two months of rule. His offense was simple: he had made his wife’s father his chief minister, which was a clear hint to his mother that it was time for her to retire to decent seclusion and give over the empress’s throne to her daughter-in-law.

The empress, who had no intention of doing so, sent palace guards to surround Tang Zhongzong as he gave a public audience. They arrested the startled emperor and led him off to house arrest, along with his pregnant wife. Instead of elevating the Heir Apparent Grandson, Empress Wu then appointed her own younger son, Zhongzong’s brother Ruizong, to be the new Tang emperor.

Tang Ruizong, in his early twenties, was intelligent but shy, and afflicted with a crippling stutter. He had no choice but to let his mother rule on his behalf. “Political affairs were decided by the empress dowager,” one court historian records. “She installed Ruizong in a detached palace, and he had no chance to participate.”

3

None of this was exactly legal, but nor was it entirely illegal. The empress had not, after all, claimed the throne—although a decree six months after Ruizong’s “accession” deepened suspicions that she intended to do so. The decree, the “Act of Grace,” changed the colors of imperial banners, the styles of dress at court, and the insignia of court officials. This was the act of a ruler founding a new dynasty: the symbolism of change.

People muttered, but Tang China was temporarily prosperous and peaceful, the farmers and peasants were well fed and well supplied, and the general agitation needed for mass revolt was missing. An armed revolt against her de facto usurpation did break out, led by a nobleman whose family had been exiled not long before, but within three months the empress’s soldiers had quelled it.

Over the next five years, the empress moved from strength to strength. As the power behind her husband’s throne, she had already proved herself to be a competent administrator, military strategist, and lawmaker. Yet despite her obvious abilities, the aristocrats of the court continued to resent the fact that the former concubine had risen to a power they could only dream of.

So the empress turned to her own people, choosing her officials from the lower classes: men of ability whose birth had previously cut them off from advancement. The aristocrats would never be her friends, but they grudgingly had to admit her strengths as a ruler. Now the common people became her loyal supporters as well, grateful for the chance to rise through talent alone.

But that was not the only brick in the base of her power. She also created a secret police, headed by the two notorious officials Zhou Xing and Lai Junchen (author of the interrogators’ handbook called

Classic of Entrapment

), who

earned the same sombre notoriety as Himmler and his aides have gained in modern times. They formed a school where they taught their trade to disciples, composed a book of instructions and elaborated many new and frightful tortures to extract confessions. These contrivances they decorated with poetic names, and displayed the terrifying battery to a newly arrested victim, who would often confess anything to avoid these tortures.

4

The empress’s power was supported not only by the men who were grateful for their elevation to high office, but also by all the others who were too frightened to object.

In 690, the empress took the final step. One of her officials asked her to assume the title “Emperor, Son of Heaven.” Like the first Sui emperor and the usurpers who had come before him, she refused—a customary act that meant nothing. A second petition signed by sixty thousand of her subjects was presented; again she refused. From his secluded palace, Tang Ruizong realized that he stood at the edge of a precipice.

He presented the third and final petition himself, asking that his mother do him the favor of removing him from the throne. The empress Wu agreed, graciously. She was coronated on September 24, 690, and Ruizong was demoted to the position of heir apparent, in which he lived, peacefully, in the safety created by his willingness to lay down power.

5

With this formal recognition of her authority, the empress Wu became emperor. Yet there was no clear path in any of the ancient rituals through which a woman could claim the true Mandate of Heaven. In order to have any hope of bolstering her real political power with sacred sanction, the empress had to assume a new persona: she had to become, like all of the emperors before her, a Son of Heaven.

And so, for purposes of court ceremonies she put on a very particular illusion of masculinity: she did not change her dress or appearance, she did not try to

appear

male, but she stepped into a created male persona with which the entire country—having no way to place a female ruler into the complex patterns of the past—agreed to interact. She named herself the first emperor of a new dynasty, the Zhou, which put her in an appropriately patriarchal role; she moved the court back to Luoyang, creating a space between her rule as emperor and her previous tenure as empress.

It was a fiction unlike any that had been practised in China before. The new emperor’s administration, which now boasted scores of talented, well-trained, competent, low-born men, was one of the strongest in recent history. Despite the black thread of terror woven through her power, the emperor was clearly capable of keeping Tang China strong and prosperous. Yet there seems to have been

no way

for the empress Wu to claim the throne without taking on this new identity. The willingness of the population to accept her as the Son of Heaven reveals not only the strength of the construct but also the extent to which it was now detached from reality.

F

OR THE FIRST FIVE YEARS

of the emperor Wu’s new dynasty, Tang China flourished—although not without a constant current of resentment and complaint from the aristocrats who had been nudged out of power by Wu’s new appointees. But the loyalty of the elevated commoners continued strong, and the emperor knew how to find sympathetic allies for her causes, be they political or personal.

She took a lover, a salesman of medical herbs named Xue Huaiyi, who became troublesome. Since there was certainly no space in the old rituals for the emperor to have a male concubine, she appointed him to be the abbot of one of the Buddhist monasteries she had endowed, a position that gave him the right to enter and leave the palace freely. He took advantage of his position to become jealous and possessive, finally burning down one of the great Buddhist temples in the city in a fit of rage. The emperor picked the strongest ladies-in-waiting at court and sent them to surround Huaiyi and strangle him. The women of the Tang court had suffered a long time from the whims of royal men; she had no difficulty finding volunteers.

6

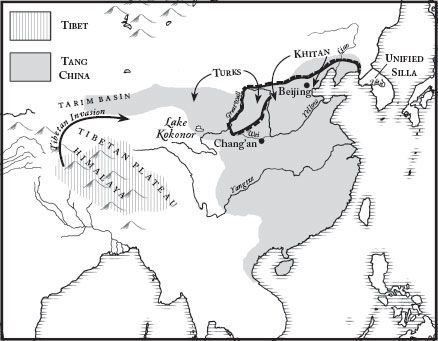

In 695, she faced a triple uprising in the north. The northern nomadic tribes known as the Khitan, who had originally lived somewhere around the Liao river, had moved south towards the Tang border and now were in the vicinity of the northern city of Beijing, headquarters of the northern military governor. At the same time, the Eastern Turkish Khaghanate, which had been under Tang rule since Tang Taizong’s conquest in 630, rebelled. The Turks of the Eastern Khaghanate had grown increasingly unhappy with their place in Tang society; they had given up their empire and fought in the Tang armies, and in return they had gotten nothing but scorn and dismissive treatment. “For whose benefit are we conquering realms?” they complained. Descendents of the old royal family still lived, and one of them, a man named Mo-ch’o, led the Eastern Turks in a rebellion. While the Khitan were invading Beijing, the Turks under Mo-Ch’o were raiding the northwestern frontier.

7

At the same time, the Tibetans began to launch attacks against the Tang land in the Tarim Basin. The Tibetan king Mangson Mangtsen, guarded by the regent Gar Tongtsen, had survived his infancy (against all odds) but then died in his twenties; by that point Gar Tongtsen was also dead, and Tibet was now controlled by Gar Tongtsen’s son Khri-’bring, acting as regent for Mangson Mangtsen’s young son Tridu Songtsen. The double passing on of power—regent to regent, emperor to emperor—provided the Tibetan empire with enough stability so that the conquests begun by Tridu Songtsen’s great-grandfather Songtsen Gampo could resume.

8

The timing of the attacks suggests that the three enemy armies were in some kind of communication. The driving force behind all three was probably the Eastern Turkish leader Mo-ch’o, who now began to work the situation to his advantage. He suggested to the Khitan that they attack; once their invasion was underway, he sent messages to Emperor Wu offering to fight the Khitan on behalf of the Tang, in return for very large payments. The former empress agreed to this plan. Mo-ch’o attacked and defeated the Khitan in 696. Then, after collecting his fee he went right back to attacking the Tang again. Within a few years, he had managed to rebuild the power of the Eastern Khaghanate. The Tibetans, meanwhile, conquered the southern part of the Tarim Basin, and Tibetan armies marched into China, getting as far as two hundred miles west of Chang’an itself. This was as far as they could extend themselves without danger of collapse, so they accepted the emperor’s offer of a buyout, took the money, and retreated.

9

44.1: Invasions of Tang China

The defeat of the Tang armies in battle made it harder for the former empress to maintain the illusion that she was the Son of Heaven. As so many aging emperors had done before her, the emperor Wu (now in her seventies) reassured herself of her potency and her power through the pleasures of the flesh. She began a dual affair with two brothers, both with the family name of Zhang. She granted them so many favors that they became the two most hated men at court, and her officials began to worry that the brothers might be able to talk her into making them her successors. An increasing number of court officials began to suggest that the retired Zhongzong should be brought back out of obscurity and restored to the throne. To silence them, the emperor brought Zhongzong out of his fourteen years of house arrest and declared him to be her successor, the Heir Apparent (despite the fact that he had already been emperor once). He was nearly fifty and had led a quiet life in semi-seclusion with his wife and children. With the amiability that had kept him alive up until this point, he accepted the title and did not press for more.

10

Emperor Wu had held on to her health and strength for an extraordinarily long time, but now she began to weaken. She suffered the first major illness of her life in 699, and despite doses from court alchemists, further spells of sickness followed. By 705, the empress was eighty years old and ready for retirement. She abdicated, handing the crown over to her son Zhongzong, and took to her bed.

There she remained for the next year, apparently still popular with her people, holding audiences in bed like the grandmother of the entire nation, until she died filled with years and glory.

11

W

ITH THE EMPEROR DEAD

, the court records almost unanimously ignored her attempts to found a new dynasty, and went right back to chronicling the years of the Tang. Zhongzong ascended as the fifth Tang ruler (or as the sixth, depending on whether or not his two months in power, back in 683, was counted as a separate reign).

The pliancy that had saved him did not make him a good ruler. For the five years of his reign, from 705 until 710, the Tang court was run by his wife, the empress Wei, and her lover, the emperor’s cousin Wu Sansi.

12

Empress Wei had ambitions to be like her mother-in-law, but she lacked Emperor Wu’s intelligence and competence. Within five years, the court was a disastrous, corrupt mess. The empress capped the disaster by poisoning her husband Zhongzong in 710. After surviving decades of court intrigue, the unfortunate man was finally brought down by a plate of cakes.