Prisoners of the North (37 page)

Read Prisoners of the North Online

Authors: Pierre Berton

Service’s Scottish heritage cautioned him to hedge his bet by laying off a half-interest in the book for fifty dollars to a fellow Scot who occasionally offered him a loan at 10 percent a month. The “village Shylock,” as Service called him, turned the offer down. “Who buys poetry in this blasted burg? … Ye can jist stick yer poetry up yer bonnie wee behind.” When later he learned what a fifty-dollar investment in

Songs of a Sourdough

might have brought him, Service joked, “I think it broke his heart.… I know,” he added, “it would have broken mine if I had been obliged to give half the dough that book brought me in royalties.”

Service typed out his selection of rhymes and sent it and a cheque to his father, now in Toronto, who peddled it to William Briggs’s Methodist Book and Publishing House, which did vanity work on the side. The poet almost immediately regretted this rash action. His inferiority complex convinced him that people would laugh at him when the book came out. “It would be the joke of the town.” He had wasted one hundred dollars.

He didn’t even bother to read the letter the publisher eventually sent. When he finally opened it, a cheque fell out; the firm was returning his money. Only when he read the letter did it dawn on him that he was being offered a contract to publish his work with a royalty of 10 percent on the list price. He could hardly believe it. “The words danced before my eyes … my whole being seemed lit up with rapture.” Service was sure that he must have a guardian angel overseeing his career. That guardian angel finally appeared in the guise of Robert Bond, a twenty-three-year-old salesman for the publisher who had been about to leave on his annual sales trip to the West when the firm’s literary editor handed him a set of proofs. “We’re bringing out a book of poetry for a man who lives in the Yukon. You’re going to the west coast; you may be able to sell some to the trade out there. It’s the author’s publication and we’re printing it for him. Try to sell some for him, if you can.”

Bond, who was already packed and leaving for the station, stuffed the proofs into his pocket and forgot about them until that night. Sitting in the diner with nothing else to read, he dipped into “The Cremation of Sam McGee.” He was so entertained that he forgot his meal and burst out laughing when he reached the final line. Across the aisle, a commercial traveller asked what he was laughing at.

“It’s poetry,” Bond told him, and the man’s face fell. “It’s unusual,” he explained, “and it’s Canadian and it might even sell.” He began to read the ballad aloud and as he read, his fellow passenger began to squirm in his chair and then, at the last line, howled with laughter. “He coughed till he choked,” Bond recounted later, “and had to leave the dining-car.”

In the smoking car after dinner, a crowd had gathered and pressed Bond to read the ballad. “When I finished,” he recalled, “bedlam broke loose—and everybody spoke at once. Some of the men even quoted lines that stuck in their memory.” Others, who had come in late, asked Bond to read the poem again. He did it several times before the night was over, so that by the time they reached Fort William he knew it by heart. He began to walk into bookstores to recite it. Whenever he was able to do that, the store ordered books.

When the first copies of

Songs

reached Bond in Revelstoke, he was appalled. “How I swore! It was a poor-looking thin book, bound in green cloth.” The company, disturbed by the frankness of some of the poems, had tried to shuck off responsibility by marking it “Author’s Edition.” To Bond the cover price of seventy-five cents was an insult; he had been quoting it to retailers at a dollar. With the first edition already on the verge of selling out, Bond urged his firm to buy the rights and sell it on a royalty basis. When the first royalty cheque arrived, Service thought there must be some mistake and wrote to ask how long the royalties might continue. Fifty years later, Bond told an interviewer, “I have no doubt he is still wondering, for certainly no Canadian poet, or possibly any poet has received as much as Mr. Service has received.”

Service near the end of his life would remark that he had made a million dollars out of

Songs

. He soon managed to increase the royalty rate from 10 percent to 15 and the publisher at once raised the cover price to one dollar, suggesting a future profit to Service of $450,000. But of course the cover price increased over the years, so that Service’s own estimate of a cool million is probably an understatement.

Only a minority of Service’s readers outside the Yukon realized that he had written the poems without ever having seen the Klondike. Most believed he had actually taken part in the great stampede, as a study of memoirs of that time makes clear. One respected author and jurist, the Honourable James Wickersham, wrote in

Old Yukon

that in Skagway in 1901, “in one of the banks, a gentlemanly clerk named Bob Service was introduced [to me].” Thames Williamson in

Far North Country

declared that “Service was in the Klondike during the fevered days of the gold rush.” Glenn Chesney Quiett made the same error in his

Pay Dirt

. In February 1934, Philip Gershel, aged seventy-one, claimed he was the original Rag Time Kid of Service’s best-known ballad. “I knew Dan McGrew and all the others,” he declared and went on to describe the Lady That’s Known as Lou as “a big blonde, tough but big-hearted.” Gershel said the shooting took place in the Monte Carlo Saloon; Mike Mahoney claimed it happened in the Dominion. “I was right there when it happened,” he insisted to an interviewer in 1936. He claimed that Lou was still alive and living in Dawson City. (James Mackay claimed that she was a cabaret performer who drowned when the

Princess Sophia

sank off Alaska—in 1918.) Mahoney, the hero of Merrill Denison’s book

Klondike Mike

, recited “Dan McGrew” so often he came to believe in it. When he was challenged at a Sourdough Convention in Seattle by Monte Snow, who had been in Dawson for all of the gold-rush period and knew that Mahoney’s story was fictitious, the assembly of old-timers gave Klondike Mike the greatest ovation of his life. They did not want to hear the truth.

Service himself felt that he ought to have been in the stampede and considered himself a bit of a charlatan because he was writing about events in which he had not taken part. In the fall of 1907, having spent three years with the bank, he was due for a three-month leave. He did not relish the idea because he knew it could lead to a reassignment that might take him away from the North. “That would be a catastrophe; I realized how much I loved the Yukon, and how something in my nature linked me to it. I would be heart-broken if I could not return. Besides, I wanted to write more about it, to interpret it. I felt I had another book in me, and would be desperate if I did not get a chance to do it.”

Fortunately, his guardian angel, this time in the form of the bank inspector, was on hand after Service took his holiday. “You’ll be sorry to hear you’re going back to the North. I have decided to send you to Dawson as teller.”

Service was more than relieved. “I was keen to get on the job. I wanted to write the story of the Yukon … and the essential story of the Yukon was that of the Klondike.… Here was my land.… I would be its interpreter because I was one with it. And this feeling has never left me … of all my life the eight years I spent there are the ones I would most like to live over.”

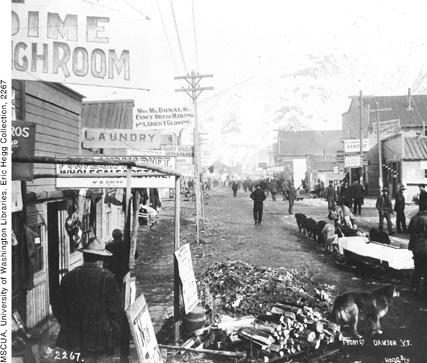

Dawson in 1908 had five times the population of Whitehorse but was on the way to becoming a ghost town. In the evenings, Service wandered abandoned streets, trying “to summon up the ghosts of the argonauts,” gathering material for another book,

Ballads of a Cheechako

. He was just far enough removed from the manic days of the stampede to stand back and see the romance, the tragedy, the adventure, and the folly. His verses sprang out of incidents that were common occurrences in the Dawson of that time: Clancy, the policeman, mushing into the north to bring back a crazed prospector; the Man from Eldorado hitting town, flinging his money away, and ending up in the gutter; Hard Luck Henry, who gets a message in an egg and tracks down the sender, only to find that she has been married for months (Dawson-bound eggs unfortunately were ripe with age). These themes were not fiction, as “McGrew” was. As a boy in Dawson, I watched Sergeant Cronkhite of the Mounted Police, his parka sugared with frost, mush into town with a crazy man in a straitjacket lashed to his sledge. As a teenager, working on the creeks, I saw a prospector on a binge light his cigar with a ten-dollar bill, fling all his loose change into the gutter, and lose his year’s take in a blackjack game. The eggs we ate, like Hard Luck Henry’s, came in over the ice packed in water glass, strong as cheese, orange as the setting sun.

My mother, then a kindergarten teacher, remembered Service strolling curiously about in the spring sunshine, peering at the boarded-up gaming houses and the shuttered dance halls. “He was a good mixer among men and spent a lot of time with sourdoughs, but we could never get him to any of our parties. ‘I’m not a party man,’ he would say. ‘Ask me sometime when you’re by yourselves.’ ”

He seldom attended any of the receptions or Government House affairs, and soon people got out of the habit of inviting him. When a distinguished visitor arrived in town, Service would have to be hunted down at the last moment, for they always insisted; and the poet, if pressed, dutifully made an appearance. My mother remembered how Earl Grey, the governor general, on a visit electrified Dawson by asking why Service hadn’t been on the guest list for a reception. “We had all forgotten how important the poet was.”

Service, who felt he had to undergo every type of experience, wangled permission to attend a hanging that fall. He stayed at the foot of the gibbet until the black flag went up and then, visibly unnerved, moved with uncertain step to the bank mess hall and downed a tumbler of whisky. It was decades before he could bring himself to compose a ballad based on that experience.

In one of his rare visits to the cottage where the kindergarten teachers lived, he discussed some of the new poems he was writing. “In his soft voice well modulated but strangely vibrant and emotional when he talked of the Yukon,” he read my mother parts of “The Ballad of Blasphemous Bill.” “I cannot say I was greatly impressed,” she remembered, “for it seemed to me a near duplicate of the Sam McGee story, and I said so.

“I mean it’s the same style—one man’s body stuffed in a fiery furnace—the other’s a frozen corpse sewn up and jammed in a coffin,” she told him.

“Exactly!” Service exclaimed. “That’s what I tried for. That’s the stuff the public wants. That’s what they pay for. And I mean to give it to them.”

Service’s thoughts, at this period, were always on his work. He danced with my mother once during one of his rare appearances at the Arctic Brotherhood Hall. In those days each dance number—waltz, two-step, fox trot, and medley—was followed by a long promenade around the floor. When the music stopped for such an interlude the absent-minded poet, deep in creation, forgot to remove his arm from my mother’s waist. As she recalled in

I Married the Klondike

, “We meandered, thus entwined, around the entire floor, and in those days a man’s arm around a lady’s waist meant a great deal more than it does now. The whole assembly noticed it and grinned and whispered until Service came out of his brown study.”

Working from midnight to three each morning, Service was able to finish the new book in four months. It consisted largely of ballads in the metre of “Dan McGrew” and “Sam McGee.” Service’s love of alliteration can be seen in the names of the leading characters: Pious Pete, Gum-Boot Ben, Hard Luck Henry. For his several character sketches of Klondike stereotypes—the Black Sheep, the Wood Cutter, the Prospector, and the Telegraph Operator—he chose a different rhythm:

I will not wash my face;

I will not brush my hair;

I “pig” around the place

There’s nobody to care.

Nothing but rock and tree;

Nothing but wood and stone;

Oh God! it’s hell to be

Alone, alone, alone.

I recall such a character when, at the age of six, I drifted with my family down the Yukon River from Whitehorse to Dawson. Above us on the bank stood a lonely cabin, and from it emerged its sole occupant, the telegraph operator. He called to us and insisted we stay for lunch—porcupine stew. When we took our leave and made our way down the bank to our poling boat, he followed. “Don’t go yet. Stay! Stay for dinner. Stay all night. Stay a week!” Every time I pick up

Ballads of a Cheechako

I think of him.

The Dawson of Service’s day was still crowded with men who had climbed the passes to reach their goal. No man caught the obsession or the fury of that moment in history better than Service had in his poem

The Trail of ‘98

—a phrase he embedded in the language. Here he used his words like drumbeats that seem to echo the steady tramp of those who plodded upward toward the summit—in a measured tread that came to be dubbed the Chilkoot Lockstep.

Never was seen such an army, pitiful, futile, unfit;

Never was seen such a spirit, manifold courage and grit;

Never has been such a cohort under one banner enrolled,

As surged to the ragged-edged Arctic, urged by the arch-tempter—Gold!

It is easy to see why so many of Service’s readers were convinced that the poet had been in the forefront of that army. As he himself put it, “It was written on the spot and reeking with reality.” He sent the manuscript to his publisher who promptly returned it, complaining of “the coarseness of the language and my lack of morality.” A brief struggle followed by telegraph, which Service won by threatening to offer the book to a rival publisher. Once published, the book became another best-seller.