Mischief (29 page)

Authors: Fay Weldon

The next day was going to be busy. The house had to be decorated, food prepared for Christmas Eve, the presents for Neil and his six cousins wrapped – well, step-cousins, three boys from her elder sister, three girls from her younger. Neil was getting a bicycle. Lone thought it would be wise if they all had presents of equal value, but Ben had said no. This year Neil would get a special treat. Lone was tempted to say better to spend time and attention than money, but she didn’t. Ben would have looked so shocked and hurt if she had.

When they got to the house, she asked Neil to help her unpack the car, but he said quite rudely no, he was going straight down to the sea before it got dark. She let him go, but it irked her and when he came back excited about a bit of old stone which he claimed was a Neolithic axe head she told him not to be silly and if he was determined to keep it to wash it before it made everything dirty.

When she showed him to his really beautiful room – the best spare bedroom all to himself, with the special Baby Elephant Feet wallpaper – he asked where his television was and she told him there was no TV in the house but he could have the radio, he said ‘What’s the use of that. I don’t understand Danish, and I never want to,’ and closed the door behind him, with just the same hurt and shocked look Ben used to get his own way. She could hear him sobbing on his bed. She tried to lure him out with pate and rye bread, and prawns and mayonnaise but he said he’d rather starve. ‘Starve then,’ Lone said, and it was her turn to slam the door. Her turn to lie on her bed too, out of frustration and guilt mixed, and weep. She couldn’t be sure whether she was more angry with Ben or with his son, or with herself for being pregnant.

The next day went rather better. Ben turned up all apologies – it really had been an emergency: a crane had toppled – and he and Neil went for a walk and came back with some more old stones, and Lone bit back remarks about dirt and mess. Later in the morning, while she prepared the meal and cooked the pork, they went to church and Neil came back saying he liked the paintings like cartoons on the walls but he didn’t know the tunes of the hymns. The family arrived and Neil nagged until he was allowed to open his present early, which meant everyone else did too, so that quite spoiled the ritual timing of Christmas Eve. When finally he did get his bicycle he said it was stupid and he didn’t know how to ride one anyway. The cousins were astonished and laughed at him but took him out into the crimson and yellow sunset and showed him how it was done. He learned quickly and within a couple of hours was doing wheelies in the lamplight with the best of them. His body language was like his father’s, and Lone, watching while she stacked the dishwasher, decided that having a son wasn’t necessarily the worst disaster that could happen to a woman.

But the next day, Christmas Day, friends and neighbours arrived and matters got worse. Neil refused to eat smorgasbord saying he wanted something hot, and though Lone piled little potatoes on his plate, with butter, he wouldn’t eat a thing and said Danish Christmases were boring, there weren’t even any crackers or paper hats. It was embarrassing for everyone.

Ben said ‘if you want to go hungry that’s fine, all the more for us,’ and Neil went to his perfect room wearing his dirty outside boots and stomped about. Then someone saw the old stones on the mantelpiece: Lone had been wrong. They were indeed worked axe and arrow heads from thousands of years ago. So Lone went upstairs and apologised to Neil for being so mean, and Neil came down with his own arrowhead and showed it round and everyone congratulated him, and Ben said perhaps his son would grow up to be an archaeologist; Neil had what Ben called ‘a natural talent: an observer’s eye.’ And once again Neil smiled, with his real smile, not the one that had been forced on him.

Lone felt a surge of affection for the boy and said she would bake mince pies for Boxing Day to make him feel at home. And with a jar of mincemeat – dried fruit and nuts with a dash of brandy: nothing to do with meat: just other countries, other customs – borrowed from an Anglophile neighbour, set about making them. Neil showed Lone how his mother decorated the pastry edges with the back of a fork, and that somehow eased things between them, now the mother had been mentioned.

Neil watched Lone work in silence for a little while, and then said, ‘Once upon a time, two hundred thousand years back, there wasn’t an English channel at all, just land all the way. I could have walked from here to home, if I’d wanted to. Seven hundred and fifty-three miles. Except there would have been wolves and tigers so it wouldn’t have been wise. You can call me Nils if you like.’

At that moment the baby kicked and Lone wanted to sit down and Nils bought her a chair without being asked. ‘Thank you Nils,’ she said. She thought it was all going to be okay, after all.

2009

It was the night before Christmas, and all through the house, not a creature was stirring, not even a mouse…

except a clot of blood, creeping up from Ted’s leg to his brain, there to burst and kill him as he slept. He’d been complaining earlier of a swelling and some mild pain in his calf, that was all.

I’d spent the day in a mood of sulky despair wishing that I were somebody else, or at least that I lived with somebody else, and even while I shopped for presents and prepared for the next day’s festivities I was planning my escape from what seemed a grievous marriage. Of course as soon as Ted died I forgot all that and the only thing that was grievous was his death. I had loved him. I still loved him. The loss of him was intolerable. I married again as soon as I could.

I can’t even remember the exact source of that day’s particular grievance. But anything would have done to fuel my resentments and keep poor Ted’s faults, rather than his virtues, mulling away in my head almost to the exclusion of all else. I was in a negative state of being, a captious, resentful mood. I do remember that I shopped ineptly that morning and in the afternoon curdled the mayonnaise, and that Ted commented: ‘Women are like the weather. Their moods blow in and out like the wind. Time of the month, perhaps?’ Which I denied, though of course it was true.

Actually I think our moods blow in with our dreams, and it’s dreams which control the matrimonial weather. Ted and I were married when I was eighteen, a week after my adoptive parents died in a car crash: they had been out shopping for her mother-of-the-bride outfit. She appeared to me the following night in a dream in which she wore the dress – pale green with flouncy bits: something of a mistake, I thought, even at the time – though in life she was never to wear it. The outfit – dress, jacket, leafy hat, satin shoes – had been found still in its Debenhams bag in the boot of the semi-submerged car. She had leaned over me where I lay in bed with Ted, and said funeral or not, take no notice of her, the wedding must go ahead. So it had.

I was with Ted for twenty years before death took him from me. There had been a lot of sex and sex usually gave me vivid dreams. When the dreams were good, and he and I lived in a pleasant dreamscape, our days would be happy and productive. When the dreams were bad our days would be clouded. When they were nightmares, when I was pre-menstrual, they would feature Ted as the bad guy even as I lay beside him in the double bed, breath and limbs as one, he sleeping peacefully and innocently enough. In those dreams I would find him in bed with Cynara his partner from the art gallery, or trying to murder Martha and Maude our twin daughters, or lunging at me with a knife while my legs would be rooted to the spot or all my teeth falling out, that sort of thing. Then I would wake up angry with Ted, and spend the whole day furious, and the emotional weather would be set cold, bleak, and judgemental.

Poor Ted, he must have had a hard time from me. I too had a hard time from my heaving hormonal states. Some of us are just more female than others. Life flowed through me in the messiest of ways. Yet to an extent one must be responsible for one’s own dreams: they happen in one’s own head. Though actually that’s the kind of thing I would have said before Robbie appeared on the scene. Now I am not so sure.

Robbie is my current husband. I married him ten months to the day after Ted died, and I’ve been married to him for ten months. My grief therapist had warned me not to ‘embark on a relationship’ so soon after my loss, but I’d ignored her. A good man is hard to find, I told her – they don’t just hang about on trees like ripe fruit waiting to be plucked – and to me ten months of celibacy seemed a very long time indeed. Robbie has been supportive, kind, generous with money and very good to me, concerned for my welfare to the extent of evening out what he calls my ‘hormonal issues’. He’s an American and a neuro-pharma-scientist, and works in a science lab with psycho-pharmacist colleagues. The distinction is that Robbie works on drug-induced changes in the cell functioning of the nervous system: the colleagues study the effects drugs have on mood, sensation, thinking and behaviour in the totality of a human being. In other words they know the right pills for someone like me to take so Robbie can have a quiet and tranquil married life and focus on his top-priority, top-secret, top-paying job at Portal Inc. in the Nine Elms area of London.

Even in the early Ted days I had taken Valium, and then for a time Prozac and they had helped. Now the drugs are more sophisticated.

Today I sit on my new leather sofa and wait for Robbie to return home from Portal Inc. It has been a rather extraordinary and exhausting day. I try to clear my head and sort out what emotion is real and what the result of psycho-pharmacology. That is to say what pills I’ve been taking, and how many and when, and why. But I’m very tired. Thoughts go round and round, and lapse into dreams.

Before I came to woman’s estate and knew better, I imagined dreams came from outside us, ‘sent’ by either God or the Devil, the good force or the bad, creeping under a cloak of darkness to get into our heads. I developed quite an elaborate cosmology when I was small. I went to a convent school where the nuns would tell me God was always watching: that I could never be alone in a room even though I thought I was: God’s eye was on me. I grew out of believing that when I became a teenager and felt the urge to pleasure myself. One believes what it is convenient to believe. I read a lot of Tolkien, and for ages saw the cosmos as largely consisting of Mordor-versus-the-Middle-Kingdom. I came to assume that if there was a good there must be an opposing bad. It was all God versus Devil, poor versus rich, worker versus boss, tenant versus landlord, art versus science. I knew which side I was on.

But since Ted died I’ve revised my rather simple vision: it seems to me now that evil is not just an absence of good, but a power in itself. A gleeful Devil does the watching the better to catch us out; and every tiny little nasty thing we say or do, every snap of temper, every flicker of meanness, every miserable act of bad faith from each of the myriad of tiny souls who scuttle about on this hurtling ball of rock of ours, is used as grist to his mill. It’s tempting to provide bad deeds for the Devil’s nourishment: he pays well, as Faust found out. The wicked flourish.

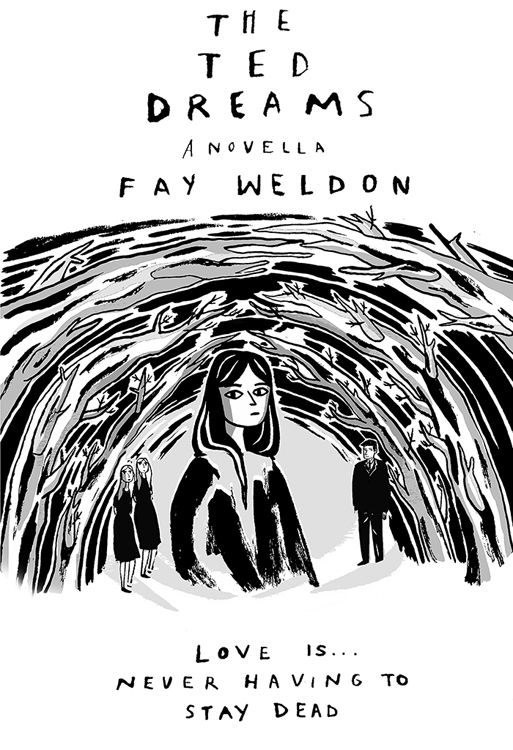

Ted flourished, which is why he now has to spend time struggling in the dark wood. These days I seem to see this place almost nightly in my dreams – a horrid place, dank and drear, but one gets used to it. I witnessed him hacking his way through the forest two or three times in the months after he died – but after I married Robbie I had the dreams more frequently. Ted is certainly in need of forgiveness. That is if Cynara, Robbie’s ex-girlfriend, was telling the truth. I had lunch with her today. She hinted she was having an affair with Ted when he died. Well, she is like that. A mine of upsetting disinformation. I have refrained from taking my normal six o’clock pill. I had better face what has to be faced.

I imagine the dark wood is my version of what the nuns of my childhood used to call Purgatory, a place where sinners are set to wandering after death, dogged by the reproaches of others; a forest where creepers cling to you and strangle you, roots trip you up, and devils flit about like mosquitoes, until you finally push through to a clearer, greener parkland where trees stand straight, tall and separate and a sun brighter than you’ve ever imagined shines through to touch your soul. Finally, I daresay, you pass out of dappled light into full sunshine. But the whole thing is metaphor anyway. I am no believer in the final full stop, mind you. I have had too much evidence to the contrary in my lifetime, though I try to make as little of it as I can.

The longer it is since Ted died the more real he becomes. In my dream last night I watched him stoop to brush away the mud of the dark wood from his shoes. They were the heavy lace-up shoes he wore when he was clearing the brambles that afflicted our nice suburban garden; shabby brown leather, not the smart loafers he wore to the gallery. They were wet from the forest. In the dream he looked straight at me and for once he spoke loud and clear: ‘For God’s sake leave me alone!’ Then he kind of faded away like the Cheshire cat in

Alice in Wonderland

, only leaving behind more of a snarl than a smile. I was able to tell myself that the dream came from my head not his, which was some comfort, but it was still the kind of thing an ex, or about to be ex, husband might say if one asked him how he was feeling or what he was doing, rather than one who was deceased. And I hadn’t said a word. I woke feeling rather shaken.