History of the Second World War (51 page)

Read History of the Second World War Online

Authors: Basil Henry Liddell Hart

Tags: #History, #Military, #General, #Other

For the troops of the Eighth Army, the fact of seeing the enemy in retreat, even though only a few short steps back, far outweighed the disappointment of failing to cut him off. It was a clear sign that the tide had turned. Montgomery had already created a new spirit of confidence in the troops, and their confidence in him was confirmed.

The question remains, however, whether a great opportunity was missed of destroying the enemy’s capacity for further resistance while the Afrika Korps was ‘bottled’. That would have saved all the later trouble and heavy cost of assaulting him in his prepared positions. But so far as it went the Battle of Alam Haifa was a great success for the British. When it ended, Rommel had definitely lost the initiative — and, in view of the swelling stream of reinforcements to the British, the next battle was bound to be for Rommel a ‘Battle Without Hope’ — as he himself aptly called it.

In the clearer light of post-war knowledge of the respective forces and resources, it can be seen that Rommel’s eventual defeat became probable from the moment his dash into Egypt was originally checked, in the July battle of First Alamein, and this accordingly may be considered the effective turning point. Nevertheless, he still looked a great menace when he launched his renewed and reinforced attack at the end of August, and as the strength of the two sides was nearer to an even balance than it was either before or later, he still had a possibility of victory — and might have achieved it if his opponents had faltered or fumbled as they had done on several previous occasions when their advantage had seemed more sure. But in the event the possibility vanished beyond possibility of recovery. The crucial significance of ‘Alam Haifa’ is symbolised in the fact that although it was fought out in the same area as the other battles of Alamein, it has been given a separate and distinctive name.

Tactically, too, this battle has a special interest. For it was not only won by the defending side, but decided by pure defence, without any counter-offensive — or even any serious attempt to develop a counteroffensive. It thus provides a contrast to most of the ‘turning point’ battles of the Second World War, and earlier wars. While Montgomery’s decision to abstain from following up his defensive success in an offensive way forfeited the chance of trapping and destroying Rommel’s forces — momentarily a very good chance — it did not impair the underlying decisiveness of the battle as a turning point in the campaign. From that time onwards, the British troops had an assurance of ultimate success which heightened their morale, while the opposing forces laboured under a sense of hopelessness, feeling that whatever their efforts and sacrifices they could achieve no more than a temporary postponement of the end.

There is also much to be learned from its tactical technique. The positioning of the British forces, and the choice of ground, had a great influence upon the issue. So did the flexibility of the dispositions. Most important of all was the well-gauged combination of airpower with the ground forces’ plan. Its effectiveness was facilitated by the defensive pattern of the battle, with the ground forces holding the ring while the air forces constantly bombed the arena, now a trap, into which Rommel’s troops had pushed. In the pattern of this battle, the air forces could operate the more freely and effectively because of being able to count on all troops within the ring as being ‘enemy’, and thus targets — in contrast to the way that air action is handicapped in a more fluid kind of battle.

Seven weeks passed before the British launched their offensive. An impatient Prime Minister chafed at the delay, but Montgomery was determined to wait until his preparations were complete and he could be reasonably sure of success, and Alexander supported him. So Churchill, whose political position was at this time very shaky after the series of British disasters since the start of the year, had to bow to their arguments for putting off the attack until late in October.

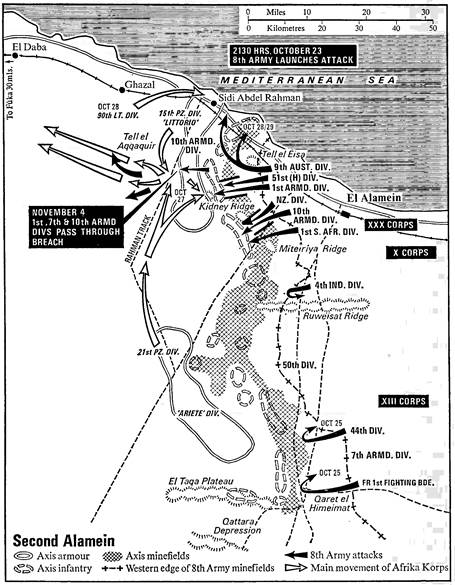

The exact date of D-day was determined by the phases of the moon, for the offensive was planned to start with a night assault — to hamper the enemy’s defensive fire — while adequate moonlight was needed for the process of clearing gaps in his minefields. So the delivery of the assault was fixed for the night of October 23 — full moon being on the 24th.

One key factor in Churchill’s desire for an earlier attack was that the great project of a combined American and British landing in French North Africa, named ‘Operation Torch’, was now planned for launching early in November. A decisive victory over Rommel at Alamein would encourage the French to welcome the torch-bearers of liberation from Axis domination, and would also help to make General Franco more disinclined to welcome the entry of German forces into Spain and Spanish Morocco — a countermove that could upset and endanger the Allied landings.

But Alexander considered that if his attack, ‘Operation Lightfoot’, was launched a fortnight in advance of ‘Torch’, that interval ‘would be long enough to destroy the greater part of the Axis army facing us, but on the other hand it would be too short for the enemy to start reinforcing Africa on any significant scale’. In any case, he felt, it was essential to make sure of success at his end of North Africa if there was a good result from the new landings at the other end. ‘The decisive factor was that I was certain that to attack before I was ready would be to risk failure if not to court disaster.’ These arguments prevailed, and although the date he now proposed was nearly a month later than Churchill had earlier suggested to Auchinleck, the postponement to October 23 was accepted by him.

By that time, the British superiority in strength — both in numbers and quality — was greater than ever before. On the customary reckoning by ‘divisions’, the two sides had the appearance of being evenly matched — as each had twelve ‘divisions’, of which four were of armoured type. But in actual number of troops the balance was very different, the Eighth Army’s fighting strength being 230,000, while Rommel had less than 80,000, of which only 27,000 were German. Moreover the Eighth Army had seven armoured brigades, and a total of twenty-three armoured regiments, compared with Rommel’s total of four German and seven Italian tank battalions. More striking still is the comparison in actual tank strength. When the battle opened the Eighth Army had a total of 1,440 gun-armed tanks, of which 1,229 were ready for action — while in a prolonged battle it could draw on some of the further thousand that were now in the base depots and workshops in Egypt. Rommel had only 260 German tanks (of which twenty were under repair, and thirty were light Panzer IIs), and 280 Italian tanks (all of obsolete types). Only the 210 gun-armed German medium tanks could be counted upon in the armoured battle — so that, in terms of reality, the British started with a 6 to 1 superiority in numbers fit for action, backed by a much greater capacity to make good their losses.

In fighting power, for tank

versus

tank action, the British advantage was even greater, since the Grant tanks were now reinforced by the still newer, and superior, Sherman tanks that were arriving from America in large numbers. By the start of the battle the Eighth Army had more than 500 Shermans and Grants, with more on the way, while Rommel had only thirty — four more than at Alam Haifa — of the new Panzer IVs (with the high velocity 75-mm. gun) that could match these new American tanks. Moreover, Rommel had lost his earlier advantage in anti-tank guns. His strength in anti-tank ‘88s’ had been brought up to eighty-six and although these had been supplemented by the arrival of sixty-eight captured Russian ‘76s’, his standard German 50-mm. anti-tank guns could not penetrate the armour of the Shermans and Grants, or the Valentines, except at close range. That was all the worse handicap since the new American tanks were provided with high explosive shells that enabled them to knock out opposing anti-tank guns at long ranges.

In the air, the British also enjoyed a greater superiority than ever before. Sir Arthur Tedder, the Air Commander-in-Chief in the Middle East, now had ninety-six operational squadrons at his disposal — including thirteen American, thirteen South African and one Rhodesian, five Australian, two Greek, one French and one Yugo-Slav. They amounted to more than 1,500 first-line aircraft. Of this total, 1,200 serviceable aircraft based in Egypt and Palestine were ready to aid the Eighth Army’s attack, whereas the Germans and Italians together had only some 350 serviceable in Africa to support the Panzerarmee. This air superiority was of great value in harassing the Panzerarmee’s movements and the immediate supply of its divisions, as well as in protecting the Eighth Army’s flow of supplies from similar interruption. But much more important for the issue of the battle was the indirect and strategic action of the air force, together with the British Navy’s submarines, in strangling the Panzerarmee’s sea-arteries of supply. During September, nearly a third of the supplies shipped to it were sunk in crossing the Mediterranean, while many vessels were forced to turn back. In October, the interruption of supplies became still greater, and less than half of what was sent arrived in Africa. Artillery ammunition became so short that little was available for countering the British bombardment. The heaviest loss of all was the sinking of oil tankers, and none reached Africa during the weeks immediately preceding the British offensive — so that the Panzerarmee was left with only three issues of fuel in hand when the battle opened, instead of the thirty issues which were considered the minimum reserve required. That severe shortage cramped counter-manoeuvre in every way. It compelled piecemeal distribution of the mobile forces, prevented their quick concentration at the points of attack, and increasingly immobilised them as the struggle continued.

The loss of food supplies was also an important factor in the spread of sickness among the troops. It was multiplied by the bad sanitary condition of the trenches, particularly those held by the Italians. Even in the July battle, the British had often been driven by the filth and smell to evacuate Italian trenches which they captured, and had thereby been caught in the open on several occasions by German armour before they could dig fresh trenches. But the disregard of sanitation eventually became a boomerang, spreading dysentery and infectious jaundice not only among the Italian troops but also among their German allies — and the victims included some of the key officers of the Panzerarmee.

The most important ‘sick casualty’ of all was Rommel himself. He had been laid up in August, before the Alam Haifa attack. He recovered sufficiently to exercise command during that battle but medical pressure subsequently prevailed, and in September he went back to Europe for treatment and rest. He was temporarily replaced by General Stumme, while the vacant command of the Afrika Korps was filled by General von Thoma — both of these commanders coming from the Russian front. Rommel’s absence, and their inexperience of desert conditions, was an additional handicap in the planning and preparation of the measures to meet the impending British offensive. On the day after this opened, Stumme drove up to the front, ran into a heavy burst of fire, fell off his car, and died from a heart attack. That evening, Rommel’s convalescence in Austria was cut short by a telephone call from Hitler to ask if he could return to Africa. He flew back there next day, October 25, arriving near Alamein in the evening — to take charge of a defence which had by then been deeply dented and had lost nearly half its effective tanks that day in fruitless counterattacks.

Originally, Montgomery’s plan had been to deliver simultaneous right and left hand punches — by Oliver Leese’s 30th Corps in the north and Brian Horrocks’s 13th Corps in the South — and then push through the mass of his armour (concentrated under Herbert Lumsden in the 10th Corps) to get astride the enemy’s supply routes. But early in October he came to the conclusion that it was too ambitious, ‘because of shortcomings in the standard of training in the Army’, and changed to a more limited plan. In this new plan, ‘Operation Lightfoot’, the thrust was concentrated in the north, near the coast, in the four mile stretch between the Tell el Eisa and Miteiriya ridges — while the 13th Corps was to make a secondary attack in the south, to distract the enemy, but not to press it unless the defence crumbled. This cautiously limited plan led to a protracted and costly struggle, which might have been avoided by the bolder original plan — taking account of the Eighth Army’s immense superiority in strength. The battle became a process of attrition — of hard slogging rather than of manoeuvre — and for a time the effort appeared to hover on the brink of failure. But the disparity of strength between the two sides was so large that even a very disparate ratio of attrition was bound to work in favour of Montgomery’s purpose — pressed with the unflinching determination that was characteristic of him in all he undertook. Within the chosen limits of his planning, he also showed consummate ability in varying the direction of his thrusts and developing a tactical leverage to work the opponent off balance.

After fifteen minutes’ hurricane bombardment by more than a thousand guns, the infantry assault was launched at ten o’clock on the night of Friday, October 23. It had a successful start — helped by the enemy’s shortage of shells, which led Stumme to stop his artillery from bombarding the British assembly positions. But the depth and density of the minefields proved a greater obstacle, and took longer to clear, than had been reckoned, so that when daylight came the British armour was still in the lanes or held up just beyond them. It was only on the second morning, after further night attacks by the infantry, that four brigades of armour succeeded in deploying on the far side — six miles behind the original front — and they had suffered much loss in the process of pushing through such constricted passages. Meanwhile, the subsidiary attack of the 13th Corps in the south had met similar trouble, and was abandoned on the second day, the 25th.