Gallipoli (23 page)

Authors: Peter FitzSimons

As Kitchener's spacious office â amazingly sparse for such a powerful bachelor, who nevertheless likes collecting porcelain and adores flowers â is just a short distance away, it is only a brief time after being summoned that Lord Kitchener's faithful Aide-de-Camp, Captain Oswald FitzGerald, delicately ushers Hamilton into the great man's presence.

The 62-year-old Hamilton knows his superior well and, despite the fact that Kitchener is less than three years older, admires him deeply. Both men are longstanding career army officers and served in the Boer War together, where for a time Hamilton had been his Chief of Staff.

Kitchener does not even look up; he simply continues writing upon a notepad on his desk, for all the world as if he is still alone. Finally, he utters the words that, if they

were

in a symphony, would no doubt come with a clash of cymbals: âWe are sending a military force to support the Fleet now at the Dardanelles, and you are to have Command.'

The most powerful officer in the British Armed Forces resumes writing his memo without another syllable uttered or even a glance in Hamilton's direction.

Other men might have required written instructions to assume command of the Mediterranean Expeditionary Force, but given that Kitchener's word is law, there is no need.

But what is Hamilton to do, exactly? Kitchener does not say.

And so Hamilton, perplexed, pauses.

Finally, aware that this most senior of his underlings is still here, Kitchener looks up and says, âWell?'

âWe have done this sort of thing before, Lord Kitchener,' Hamilton replies. âWe have run this sort of show before, and you know without saying I am most deeply grateful, and you know without saying I will do my best and that you can trust my loyalty â but I must say something â I must ask you some questions.'

48

Kitchener's frown and shrug in reply says it all: if you really must. But at least he does provide real information.

Hamilton will be leading some 30,000 Australian and New Zealand troops, a good mob already under the command of General William Birdwood, together with the 19,000 men of the British 29th Division under Major-General Sir Aylmer Hunter-Weston â who have at last been despatched two days before; the Royal Naval Division with 11,000 sailors turned soldiers under Major-General Archibald Paris; and a French contingent about 17,000 strong under Hamilton's old war comrade General Albert Gérard Léo d'Amade. All up, Hamilton would have about 80,000 men at his command, of whom at least 60,000 would be able to bear a rifle and take their place in the firing line.

Such talk starts to stir something deep within Kitchener. His huge moustache quivering as he speaks, the great man now gets up from behind his desk to start pacing the room and begins to wax lyrical as to the tremendous military opportunity that awaits Hamilton.

Why, with just this one clever strategic thrust, they might be able to swing the wavering Bulgarians and Rumanians to the side of the Allies!

âBut,' says Kitchener to Hamilton with an airy wave of the hand, âI hope you will not have to land at all. If you

do

have to land, why then the powerful Fleet at your back will be the prime factor in your choice of time and place.'

49

Kitchener's vision for the use of Hamilton's troops is clear. They are not really a force of invasion to neutralise the guns, rather a mopping-up operation to be unleashed

after

the fleet has secured the Dardanelles, to round up the devastated Turkish troops before pushing on to take Constantinople.

Perhaps, Hamilton wonders, some submarines could help?

Kitchener agrees entirely but insists on the singular, not plural.

âSupposing,' he says, âone submarine pops up opposite the town of Gallipoli and waves a Union Jack three times, the whole Turkish garrison on the Peninsula will take to their heels and make a bee line for Bulair.'

50

Now, Winston Churchill has passed on to Kitchener that he is desperate for the General to leave within hours and has put on a special train ready to leave that afternoon. However, Kitchener is more circumspect, saying that there is âno need to hustle'

51

as Hamilton must have enough time to get himself organised. In fact, he can have until tomorrow afternoon.

(At least in that time, Hamilton's Chief of Staff, General Walter Braithwaite, may be able to throw together a senior staff to help Hamilton.)

Typically, Hamilton's instructions are the Lord's alone. There is no input from the War Council, the British Cabinet, or the Cabinets of any of the dominions from which many of the soldiers come, like the Australians and New Zealanders.

He is Lord Kitchener.

He

decides.

He

has decided.

MORNING, 13 MARCH 1915, OFF THE DARDANELLES

No, the

AE2

has not seen action yet, but surely they are close. And it is stupendous to be here, based in Port Mudros on the Greek island of Lemnos with the rest of the Eastern Mediterranean Squadron and going out on daily surface patrols like this one.

Today, they are patrolling off the mouth of the Dardanelles, ensuring that no Turkish or German vessel comes out to launch a raid. As usual, Stoker spends much of his time working out the possibilities of taking his sub right up the Dardanelles, under the minefields, and doing what the British surface fleet has so far proved incapable of â getting through to the Marmara Sea and creating havoc.

True, the officers of the Royal Navy claim that âthe feat is impossible'

52

, but Stoker is not so sure.

Yes, the navigation would be tricky, as would the minefields and avoiding the artillery in the forts. The current at the Narrows is a nightmare â with the fast surface current from the Sea of Marmara to the Aegean, countered by an equally strong undercurrent coming back â thought to be between one and five knots, swirling against them and constantly throwing them off course. And it is also true that one French sub â

Saphir

â has already come to grief trying to accomplish it.

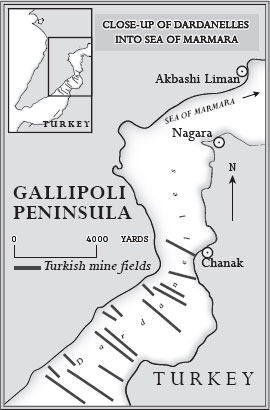

But Stoker still thinks it might be possible. The key, he decides, is to go in darkness and spare the batteries by using the engines to go as far along the surface as possible before diving under the minefields and bringing the periscope up again around Chanak, to get their bearings. After a final dogleg around Nagara Point, the Straits widen out again and things will hopefully become easier and safer.

It could be done!

Stoker is sure of it and, as a matter of fact, so sure that he soon writes it down in memo form and sends it off, via his friend Lieutenant-Commander Charles Brodie, who works with Carden's Chief of Staff, Commodore Roger Keyes. Until recently, Commodore Keyes had run the Submarine Service and is said to be something of a man of action who might be open to supporting a daring attempt.

The dogleg at Nagara, by Jane Macaulay

âThe feat could be performed,' Stoker respectfully assures him, âif one exercises the greatest possible care in navigation.'

53

AFTERNOON, 13 MARCH 1915, LONDON, HAMILTON TAKES HIS LEAVE

Typical Kitchener. After a frantic 24 hours of preparation, Hamilton now comes to say farewell to head off on the most important military operation of his career, and yet there is nothing in Kitchener's manner that acknowledges the scale of the task that has been set him. Hamilton matches the tone, and, as he will later describe it, says, âgood-bye to old K. as casually as if we were to meet together at dinner'.

54

As Hamilton picks up his cap from the desk to take his leave, Kitchener says, âIf the Fleet gets through, Constantinople will fall of itself and you will have won, not a battle, but the war.'

55

Erm, yes ⦠quite.

There is little time, however, to reflect on such portentous words as the far more important task is to get to Charing Cross Station in time for the 5 pm special train on standby to take Sir Ian to Dover, in the company of the 13 officers who have so hastily been thrown together to form his HQ staff. As recorded in Hamilton's diary, they âstill bear the bewildered look of men who have hurriedly been snatched from desks to do some extraordinary turn on some unheard-of theatre. One or two of them put on uniform for the first time in their lives an hour ago. Leggings awry, spurs upside down, belts over shoulder straps! I haven't a notion of who they all are.'

56

And, yes, Hamilton has always known that he is on an important mission, but that fact is highlighted by the presence of none other than Winston Churchill

and

his wife, Clementine, waiting there on the platform to see them off, in the company of a few âdazed wives'.

A word, if you will, General �

In crisp tones, First Lord of the Admiralty Churchill urges Hamilton to make haste, once in the Dardanelles, to land on the Peninsula whatever troops he can get his hands on, as quickly as possible. It is imperative the Turks have no more time to build their defences, don't you see?

(If Churchill is appearing desperate, it is because he is. He needs some success in this venture that he has sponsored from the outset, and he needs it quickly. For Churchill is now, in the words of Prime Minister Asquith to his wife, Margot, âby far the most disliked man in my cabinet ⦠He is intolerable! Noisy, long-winded and full of perorations. We don't want suggestions â we want wisdom!'

57

Only success in the Dardanelles will prove he has the latter.)

No, First Lord of the Admiralty, he doesn't see it like that at all.

Hamilton sees that it is his duty to do

exactly

as Lord Kitchener has asked: wait until the crack 29th Division under General Hunter-Weston has arrived.

Perhaps mercifully for General Hamilton, there is little time to discuss it, for with the locomotive hissing its steamy impatience and the conductors hovering, wanting these highly esteemed passengers to nevertheless get â

All aboooooard!

', there are many hurried handshakes, familial embraces and wishes for a safe journey and a good result. Then, at last, just after General Hamilton kisses his wife, Jean, goodbye, the train pulls away.

Yes, such partings are always emotional. But, of them all, it is the most experienced man of the lot, Hamilton, who appears the most affected.

âThis is going to be an unlucky show,' he says morosely to Captain Cecil Aspinall, his General Staff Officer, beside him in the carriage. âI kissed my wife through her veil.'

58

Soon enough, London falls behind in the backward night, and for the first time in 24 hours Hamilton has the luxury of a small time of reflection on the task ahead.

All else being equal, they are just four and a half hours from Calais, where another special train will be waiting to take them to Marseilles, where HMS

Phaeton

will rush them east across the Mediterranean Sea to the Dardanelles.

But do we have our intelligence reports?

Yes, indeed.

It will be Hamilton's claim â later heavily disputed â that at the time of his departure the sum total of all the intelligence he could gather about the likely field of battle was contained in the tiny manila folder he now carries with him. It comprises: a report on the defences of the Dardanelles, written in 1908; a very rough map drawn up in 1908, based on a French survey from 1854 for the purpose of the Crimea War; and a 1912 handbook on the Turkish Army.

LATE EVENING TO EARLY HOURS, 13â14 MARCH 1915, KEYES TRIES TO OPEN THE DOOR

This time, maybe they can do it. This time, beneath a sliver of moon, all the minesweepers are now manned by naval volunteers. They should have the backbone for the task of clearing the minefields from the Dardanelles.

After yet one more debacle two nights earlier, when the minesweepers had turned tail and fled as soon as they had been fired upon â there have now been seven minesweeping attempts for no mines destroyed â Carden's Chief of Staff, Commodore Roger Keyes, has now become heavily involved in reorganising and re-energising the whole effort. (This is typical of him. As a child growing up in India where his father had commanded the Punjab Frontier Force, Keyes is reputed to have announced, âI am going to be an Admiral,'

59

and kept up his energy towards that goal ever since.)

âIt does not matter if we lose all seven sweepers,' he tells the new recruits. âThere are twenty-eight more and the mines have

got

to be swept up.'

60

The plan this time is to get the seven minesweepers, protected by the cruiser

Amethyst

, the battleship

Cornwallis

and several destroyers, through the minefield and then have them turn and work their sweeps â the always strong current behind them â on the way back down.