Eden's Outcasts (51 page)

Authors: John Matteson

The last of the quartet of happy women, identified only by the initial “A,” was a self-portrait. Louisa introduced “A” as “a woman of strongly individual type, who in the course of an unusually varied experience has seen so much ofâ¦âthe tragedy of modern married life' that she is afraid to try it.” She called herself “one of a peculiar nature” who, realizing that an experiment in matrimony would be “doubly hazardous” for her, had instinctively chosen to remain unmarried.

70

As in her journal entry about Anna, Louisa spoke of her writings as a metaphorical family. Perhaps, she suggested, the offspring of her devoted union with literature might be unlovely in the eyes of others. Nevertheless, they had been a profitable source of satisfaction to her own maternal heart. Love and labor, she said, accompanied her like two good angels and her divine Friend had filled her world with strength and beauty. Thanks to these kind influences, she pronounced herself “not unhappy.”

71

Much meaning can be intuited from double negatives, though in this case the inferences are far from clear. Earlier in the column, Louisa had not hesitated to confer the label of “happy” on her three figurative sisters in celibacy. Her self-assessment was more ambivalent and guarded. Was her self-deprecation merely a modest observance of authorial etiquette, or did she really doubt her contentment more than that of the other independent women she knew? It was very much in character for Louisa to understate her sense of good fortune. In any event, it would have been more comforting if Louisa had advanced more positive reasons for not marrying. Her argument would have been more appealing if she had refrained from calling her own situation “peculiar” and from confessing her own dread of matrimony. Nevertheless, she sounded an inspiring note when she urged her young readers to choose their paths without fear of loneliness or ridicule, to cherish their talents, and to use them, if they chose, for higher, greater purposes than convention decreed. The world was full of work, she wrote, and never had there been a greater opportunity for women to do it.

In the first two months of 1868, Louisa behaved as if she wanted to do all of the world's work by herself. She was finding, to her annoyance, that

Merry's Museum

was demanding much more of her time than had been promised. Relations with the magazine's management were so unpleasant that, nine years later, she still described them as “very disagreeableâ¦throughout.”

72

She wrote eight long stories and ten short ones, read and edited stacks of manuscripts for

Merry's Museum

, and found time to act in a dozen stage performances for charity. On February 17, she had been buoyed by a visit from her father, who was eager to share his plans about his own book, which was finally near enough to completion that he was ready to show the manuscript to prospective editors. This book,

Tablets

, was the philosophical volume about gardening and domesticity that Bronson had first conceived near the start of the Civil War; it had been a protracted labor of love for him ever since.

Bronson escorted Louisa to a meeting of the Radical Club. One assumes that Louisa bore the evening's entertainment graciously. Afterward, however, she told her journal that she had been regaled by “a curious jumble of fools and philosophers.”

73

After passing the night in Gamp's Garret, Bronson called on Roberts Brothers. To his great delight, Roberts responded warmly to

Tablets

and agreed to publish it. Always ready to put in a word on Louisa's behalf, Bronson also mentioned the book for girls that the firm had proposed to Louisa the preceding fall. Although Louisa had evidently given up on the project, Roberts Brothers was still under the impression that the book was going forward and was expecting at least two hundred pages by September at the latestâthe same month they meant to publish

Tablets

. The literary partner of the firm spoke highly of Louisa's abilities and prospects; obviously they were expecting great things from her.

Bronson was still unfamiliar with the names at Roberts Brothers when he told Louisa the news. At first, he wrote that the partner who had spoken so warmly of his daughter was Mr. Nash. Before sending the letter, Bronson scratched out his mistake and wrote in the name that Louisa already knew: Thomas Niles. Bronson's usually horrendous business sense was, for once, leading in the right direction. He saw correctly that Niles had sensed enticing possibilities in handling both his work and Louisa's simultaneously. Bronson wrote to Louisa that his visit to the firm had turned “a brighter page” for both himself and Louisa, both “personally and pecuniarily.”

74

He urged her to come home and get to work on the story.

Louisa was reluctant to make any change. However, for reasons that are not precisely clear, she concluded that, once again, she was needed at home. Thus, on February 28, she packed up her belongings, spent one last evening acting for charity, and rode back to Orchard House the next day. Contrary to her father's wishes, Louisa did not begin at once on her girls book. The steady income from her other tales and from

Merry's Museum

was serving to provide her mother with a host of comforts. The sight of the aging woman, nestled in her sunny room and free from the anxiety of debt, meant more to Louisa than any personal success. Months passed, and still Louisa procrastinated. In May, Bronson was again in touch with Niles. Since Louisa had made no progress on the book for girls, he asked whether she might satisfy Roberts Brothers by writing a fairy book instead. Niles, however, remained firm. Louisa still balked at the idea. “I don't enjoy this sort of thing,” she wrote. “Never liked girls or knew many, except my sisters.”

75

Perhaps a good story might be fashioned out of the Alcott girls' lives, but Louisa thought it unlikely. She consulted her mother, Anna, and May and found that they all approved, and she might go ahead with the idea.

“Plod away” was Louisa's own phrase for it.

76

Ever since

Moods

had failed to win the critical adulation she had wanted, she had found it hard to think of her writing as an aesthetic pursuit. Increasingly, it was her professional discipline, not her creative spirit, that fueled her vortices and kept her at her task for hours at a time. Nevertheless she acknowledged that Niles was right in principle: there were too few simple, lively books for girls. With no particular enthusiasm for her task, in a mood not much better than that of the character she was about to create, she picked up her pen and began to write: “âChristmas won't be Christmas without any presents,' grumbled Jo, lying on the rug.”

MIRACLES

“Genius is infinite patience.”

â

LOUISA MAY ALCOTT,

quoting Michelangelo in a letter to

John Preston True, October 24, 1878

I

T WAS NEVER LOUISA'S PREFERENCE TO SIT STILL, NOT EVEN

when she was engrossed in a writing vortex. Whereas Bronson was most comfortable in his study, surrounded by his books and journals and seated at his large mahogany table, his daughter often moved about restlessly, too stirred by her ideas to remain wholly stationary. On those occasions when she took up a position on the parlor sofa, the family approached at their own risk. It was not a pleasant experience to pose an innocent question to Louisa just when her mind was working through a delicate thought or a complex sentence. At some point, though, a system was developed. Next to her, Louisa would keep a bolster pillow, which acted like a tollgate for conversation. If the pillow stood on its end, the family was free to disturb her. If the pillow lay on its side, however, they should tread lightly and keep their interjections to themselves.

For the most part, though, Louisa wrote in her bedroom at the desk that Bronson built for her. A wooden semicircle, painted white and attached to the southern wall, it is no more than two and a half feet wide. Apart from the graceful curving of the three supporting pieces underneath it, it is utterly plain. What matters about the desk is simply that it is there and that Bronson took the trouble to make it. It was then uncommon for women to be supplied with desks of their own. The desk was a gesture of Bronson's confidence in Louisa and a mute assertion that he saw the value of what she was doing. The desk is situated between two windows that look out on Lexington Road, but one must turn in one's chair to look out of these windows. Staring straight ahead, Louisa would have seen only the bare wall in front of her: the blank canvas of inspiration.

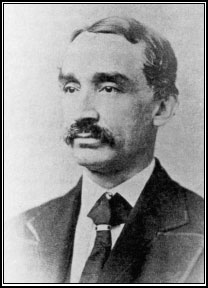

Thomas Niles, Louisa's editor at Roberts Brothers, found the first dozen chapters of

Little Women

“dull.” Then he showed them to his niece.

(Courtesy of the Louisa May Alcott Memorial Association)

For this book, however, inspiration was a thorny issue. If Louisa took pleasure in writing

Little Women

, she never said so. Giddy excitement and an innocent faith in her own genius had motivated

Moods

. The righteous cause of freedom had gotten her through

Hospital Sketches

. Now she began working as hastily as ever, but more with a view to filling Niles's order than with any high ambition. Indeed, she later recalled intending to prove to him that she could not write a successful girls book.

1

She partly hoped that Niles would see for himself that

Little Women

was an uninteresting hash and would leave her to her potboilers and

Merry's Museum

. She came close to convincing him. In June, she sent him the first dozen chapters. He thought they were dull, and Louisa agreed, but she pressed onward.

2

As she worked, a word of encouragement came. Niles told her that he had shown the early chapters to his niece, Lillie Almy, who had laughed over them until she cried.

3

Niles revised his earlier judgment; he had been reading with the eye of a literary editor, not the sensibilities of an adolescent girl. Seen by a reader whose viewpoint really mattered, the early chapters of

Little Women

had attractions he had failed to recognize. Louisa now pursued the project so single-mindedly that, from the day in June when she complained about the flatness of her first twelve chapters, she did not take time out to write a single entry in her journal until July 15, when she announced that the book, or more accurately, the portion now known as part 1, was complete. In two and a half months, she had written 402 manuscript pages.

4

The work, reluctantly begun, had eventually absorbed her. At the end of it, she had briefly broken down. Years later, she remembered her effort as “too much work for one young woman.”

5

Considering the depth and duration of the creative vortex from which she now emerged, it is not surprising that Louisa was thoroughly exhausted, her head feeling like a great mass of pain.

6

Her vortices had always been a combination of lavish creative self-indulgence and harsh physical self-denial. Now that Louisa was in her midthirties and prematurely frail, the experience of the vortex was more harrowing than gratifying. Nevertheless, Louisa knew only one way to write a novel. An iron will, rather than a poetic muse, seemed her strongest creative ally.

She hoped, but could not be sure, that there would be a part 2. Niles, for his part, was now convinced that the book would “hit.” He showed the twenty-two-chapter manuscript to the daughters of some other families, who pronounced the story “splendid!” Hearing of their approval, Louisa wrote, “It is for them, they are the best critics, so I should be satisfied.”

7

Niles had but one request; he wanted Louisa to add a twenty-third chapter with some teasing allusions that would open the way for a sequel. Louisa promptly obliged, concluding with this overt appeal:

So grouped the curtain falls upon Meg, Jo, Beth and Amy. Whether it ever rises again, depends upon the reception given to the first act of the domestic drama, called “LITTLE WOMEN.”

8

On August 26, when the proofs of the book arrived, Louisa was pleased to find that

Little Women

, in her still-cautious judgment, was “better than I expected.”

9

With pleasure, Louisa observed that her story was “not a bit sensational, but simple and true, for we really lived most of it.” If the book did become popular, she thought, its success would be due to these qualities.

10

Yet there was also a complexity to what she had written, deriving from the fact that her concept of the book evolved considerably between the writing of the first dozen “dull” chapters and those that followed. Her idea of the book was to change yet again as she worked her way through part 2. Starting as a mere job that lacked a clear plan of development,

Little Women

meta-morphosed into a carefully conceived whole, satisfying its readers even as it deliberately defied their wishes and expectations.

Properly seen,

Little Women

is not one book but three, each with its peculiar strengths and curiosities. The first phase of the book's development concerns the first dozen chapters that, on first reading, Alcott and Niles found lacking in interest. In retrospect, it seems odd that they thought so, since many of the most indelible moments of the novel occur in those first twelve chapters. To a reader who has smiled at the March sisters cheerfully surrendering their Christmas breakfast to a more needy family; who has shared Meg's injured pride as she compares her shabby wardrobe to the finery of Annie Moffat; who has felt outrage when Amy burns Jo's treasured manuscript, only to have that feeling yield to dismay when Jo's retaliatory neglect causes Amy to fall through the iceâto such a reader, Louisa's harsh preliminary judgment of these chapters can come only as a surprise. Not only are the anecdotes of these chapters rich and memorable, but the four girls are never more vivacious and entertaining. The very fact that they begin the novel so deeply flawed and prone to mishaps makes them in some ways more interesting than in the later portions of the novel, when they have gained more self-control.

Nevertheless, Louisa's judgment had some merit. In these early chapters, she was developing characters and spinning out a series of vignettes of family life, but she was not yet writing a novel. Each of the early chapters could almost stand as a short story in itself. The stronger thematic links needed to construct a larger framework have yet to appear. A certain flatness to her plot also derives from the fact that the March sisters' motivations are all fundamentally similar. Each one has to overcome a particular defining vice: Meg struggles with her vanity; Jo with her temper; Beth her debilitating shyness; and Amy her selfishness. The inward battles of the four are sympathetically rendered, and they are realistic enough to have given encouragement and comfort to countless young readers trying to master similar faults. Yet the theme of moral struggle presented a problem for the development of the larger work: if each character were defined by a single flaw, what was to keep them from collapsing into sameness once those flaws were under control? Alcott had not fully worked out the answer to this question as she wrote these early chapters. Indeed, the unifying element at this stage of her work was not her concept of plot, but rather the sustained analogy that she constructed between her emerging text and another book that she and much of her readership already found familiar.

The text that underlies the first half of

Little Women

is

The Pilgrim's Progress

, the book that had directed Bronson's ethics from childhood and which he had passed on as a moral talisman to his daughters. Louisa's reliance on Bunyan's allegory is deliberately transparent, as reflected in several of the early chapter titles: “Beth Finds the Palace Beautiful” “Amy's Valley of Humiliation” “Jo Meets Apollyon.” Alcott also acknowledges her debt to Bunyan by prefacing her novel with an adaptation of the poem that precedes part 2 of

The Pilgrim's Progress

. In the original verse, Bunyan addresses his book as follows:

Go then, my little Book and shew to all

That entertain, and bid thee welcome shall,

What thou shalt keep close, shut up from the rest,

And wish what thou shalt shew them may be blest.

11

In her story itself, however, Alcott does not passively imitate Bunyan. She is continually revising her model in order to state her own ideas about the nature of morality and a well-written book. Alcott reiterates the quoted lines in her preface but alters the third to read, “What thou dost keep close shut up

in thy breast

[italics added].”

12

Her emendation figuratively transforms her book into a living being, offering not merely moral prescriptions but the feelings that give them their practical truth. Alcott's substituted words infuse her text with greater intimacy and a more feminine sensibility. Bunyan describes a recollected dream; Alcott speaks from the previously locked precincts of her heart.

Although the specific references in

Little Women

tend overwhelmingly to concern part 1 of

The Pilgrim's Progress

, the larger thematics of Alcott's novel are more closely related to the lesser-known second part of Bunyan's allegory. In Bunyan's part 1, Christian sets forth alone to seek salvation while his wife, Christiana, timidly remains behind with the couple's children. It is only in part 2 that Christiana, who previously doubted her husband's sanity, realizes that Christian was offering her the only path away from destruction and that she and her children must now follow in his footsteps to the Celestial City. She tells her children:

I formerly foolishly imagin'd [that] the Troubles of your Fatherâ¦proceeded of a foolish fancy that he had, or for that he was over run with Melancholy Humours; yet now 'twill not out of my mind, but that they sprang from another cause, to wit, for that the Light of Light was given him.

13

Bronson Alcott, of course, had also passed through his “foolish fancies” and “melancholy humors” before finding the light that had saved him. The dominant question in part 1 of

Little Women

is the same that animates part 2 of

The Pilgrim's Progress

: will the family of a sanctified but now absent father be able to follow him to salvation?

While intentional, Louisa's invocations of

The Pilgrim's Progress

are also ingeniously ironic. Alcott resists mimicking the trajectory of the earlier work and wryly questions its moral conclusions. Whereas in Bunyan's allegory the spirit saves itself only by moving outward and away from the familiar and the domestic, the movement advocated in

Little Women

is circular. Although Jo, Amy, and Mr. March all leave home to find a place in the larger world, their redemption requires each of them to come home. Alcott also illustrates, Bunyan's allegory notwithstanding, that the process of moral transformation need not require any physical journey at all. In

Little Women

, the principal school of ethics, especially in those chapters most strongly influenced by Bunyan, remains the home.

In recasting Bunyan's moral drama in a realistic, female-dominated setting, Alcott makes a claim on behalf of the domestic sphere, arguing that the character formation that takes place in kitchens and parlors is every bit as important as the soul-making that takes place during Christian's masculine odyssey.

Little Women

expands and improves on Bunyan's allegory by reminding us that, contrary to what

The Pilgrim's Progress

may suggest, moral improvement is seldom an individual pursuit. Although each of the March sisters wrestles separately with a signature weakness, they are present to assist in one another's struggles, and it is as members of a community that they reap the benefits of their heightened virtue. In Bunyan's expression of Christian ethics, there is a core of selfishness: one is to save one's own soul even if it means leaving others to perish. For the March family, however, salvation is unthinkable in the absence of good works, and we are meant to agree with Jo when she exclaims, “I do think that families are the most beautiful things in all the world!”

14

Home is the Celestial City toward which the March sisters always unconsciously strive.