Eastern Inferno: The Journals of a German Panzerjäger on the Eastern Front, 1941-43 (34 page)

Read Eastern Inferno: The Journals of a German Panzerjäger on the Eastern Front, 1941-43 Online

Authors: Christine Alexander,Mason Kunze

Tags: #Bisac Code 1: HIS027100

It is beyond comprehension that, despite the proximity of the front, we are still able to enjoy a quiet moment, a moment where we can dream and reflect. Surrounding our little stove is not only a cloud of warmth but also our silent emotions. We sit around and smoke, interrupting the silence with only a few sentences.

The sun sets, blurring the outlines of the landscape mellowing our hardship at the front.

And now it is time for toasted bread. Our stove has reached the right temperature and now the pleasant ceremony of the soldier starts. We cut large slices of the dark bread and place it on a plate in the stove. The slices turn brown and crispy; the unforgettable smell of the bread fills the cramped space of the bunker. It is a smell which reminds us of long lost days, of the coziness and the pleasantness of the world. There are many ways to toast the bread, which permits you to distinguish the characteristics of the people in the bunker: the greedy person, the easy person, the unconcerned person, and apathetic person. The experienced toaster is patient, but will start dreaming when he stands at the stove and becomes distracted from the bitter reality, if only for a short time.

A pitch black night has now fallen outside. The first shots are fired, shells howl in the icy snow storm. The fleeting pictures of our homeland pass quickly; the fine blue smoke from our toasted bread has vanished; the trenches demand once again the full attention of every soldier. In come the impacts from shells; more and more impacts—thousands, tens of thousands—countless shells without any break. One cannot distinguish anymore between each explosion. It is now a continuous noise of bursting and cracking, a never ending infernal noise. The time does not pass, every minute feels like an hour.

We crawl into our bunkers and snow dugouts. In the beginning we are still talkative, but then we become more and more silent. We are hoping that the explosions will stop and the enemy will attack. Right now we have to endure this endless drumbeat.

Outside the landscape slowly changes its snowy appearance. Shrapnel destroys the camouflage and shakes the snow from the branches. The howling storm whirls the snow in all directions. But the noise of the explosions is drowning out the howling of the wind. The explosions singe the earth and eat up the snow which has turned into a green and black mass covering the ground. Hot pieces of metal—tiny splinters and jagged pieces as big as your palm—howl through the air. This has been going on for three days and nights, interrupted only by short breaks. The fire stops only when the Bolsheviks attack. But since we beat them back every time, despite their tanks and superior numbers, their horrible shell fire starts again every time and engulfs our positions with a widespread and incomparable vengeance. And then, slowly the whiteness of the snow turns black.

The Reds deploy their people and weaponry brutally and recklessly. Here and there they succeed in breaking through our front. Their losses are just as heavy as ours. A few comrades are lying quietly at the bottom of the trench; snowflakes have settled on their stony faces.

It is Sunday. An eerie quietness covers the desolate landscape after the embittered fights during the last three days. The naked winter soil is exposed by the torched Bolshevik tanks. And there are many such dark blotches in the terrain, motionless and silent.

We get used to the fact that enemy attacks continue to be followed by more attacks, even after we mowed them down more than ten times. We get used to the earthen-colored masses of enemy troops which seem to grow out of the soil and advance like a steamroller, yesterday, today, and certainly tomorrow. Many times we ask ourselves during the few, quite hours between the attacks: did the dead awaken again?

All thoughts stay focused on the present moment when barrages surround us day after day, when volleys of explosive charges are hurled at us, grenades howl without interruption, when bombs explode and tanks shriek. All our actions and thoughts are concentrated on survival. And we learned to hate. We have seen our comrades lying on the ground, barely recognizable; even so, he was dear and precious to us. Late in life we learned to hate, this wasn’t in our nature; and to think that everything used to be so smooth before. But it is not too late.

We receive our mail. The content is more serious than it has been during the past weeks. It reveals to us the mood in our homeland and their worries about us. Our fights are tough and relentless as never before. We know that they are aware of this back home. It is now a fight for survival, a fight for everything.

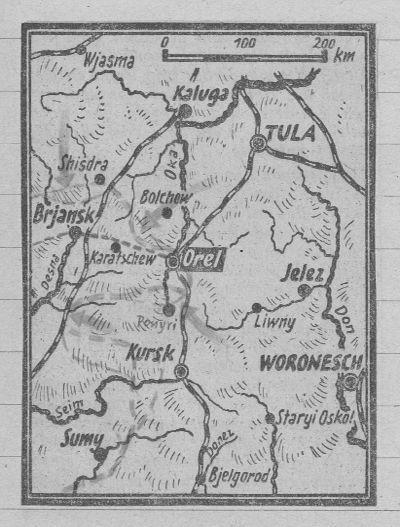

Orel

About twenty white beams are scanning the sky. This is the night of the bombers. Yesterday Russian planes dropped propaganda leaflets; they announced terror attacks and advised the civilian population to leave the city. Bombs of all sizes fall through the night. Countless fireworks and magnesium cluster bombs—also known as

Christbaume

[Christmas trees] illuminate the night sky with a dark red glow, the exploding anti-tank shells fall down like sinking stars and the yellow flashing of shrapnel bombs—a true

Hexensabbath

[witches’ Sabbath]. This night brings heavy losses for our men and our weapons. On account of these hellish nights, our meals for the next weeks consist only of margarine and minimal rations.

Map of the Orel sector of the Eastern Front.

It has now become quieter on the front. On one early morning we are told to move from our present position to support our comrades further back. We are six kilometers behind the main front line, which is very close to the rear limit. After ten hours of refreshing sleep which was interrupted only twice by Ivan’s bombs, we are in a good mood and enjoy our breakfast. It is a picture of almost tranquil peace under such circumstances, and we are very astonished when our

babushka

gets busy moving all her pitiful belongings to safety. She takes the few pictures and the completely blind mirror from the wall and removes the icon out of the corner. I ask her what the purpose of this is, but she hesitates to give me an answer. My comrades pack their belongings in the meantime. Our experience with previous retreats has taught us that when the civilians start to pack their belongings, it is time for us to get ready as well.

In January we were in Budjennij and Walniki; in February, Woltschausk and Bjelgorod. It is always the same—we establish our billets in the village huts, or in the stone buildings which at least have windows.

The local people greet us with joy and servility, reading every wish from our lips. We lay down to recover from our previous sleep deprivation. When we wake up we call Matka [one of the women in the hut], as the fire went out during the night and we are freezing horribly. But nobody shows up. We look around; the entire family has vanished.

We wait hours for an explanation, hours of almost unnatural Sunday quietness. Suddenly fire and explosions surround us again. We are already familiar with this grinding sound, interrupted only by short moments of silence, and then the heavy shower of the barrage impacts. The infernal concert started at sunset and lasted without break almost until midnight. And then, suddenly and abruptly, it stops just like it had begun. Then we hear the alarm. The Soviets have broken into the city; the nightly fight for the buildings has started.

The civilian population had already escaped from Bjelgorod a week before its capture by the Soviets. But we scoffed at such an ambush by the Reds, for we had considered it impossible. The front was far, very far. Then one morning there were no more civilians in our billet, but the Russian tanks were in front of the buildings.

We learned our lesson. With mixed feelings we remember now the hasty preparations of our

babushka

. Our good mood is gone. All the civilians in the other quarters have also vanished without a trace. The famous rats have left the sinking ship.

We should dismantle our telescopes; we are going to be facing a lot of problems! We have known these guys long enough. The civilians usually stay in their huts like cockroaches; they don’t flee when they are threatened by bombs or grenades. But the civilians have now escaped, since they were expecting the Red attacks to go building by building. Their communication system is creepier than all the tribal drums in Africa. By nightfall almost every civilian has disappeared, silently like a bad stench.

There is an unusually loud rumbling and cracking around 1900 hours toward the front. A little bit later a messenger from our regiment arrives and alerts us that the Reds have broken through the front line and are now at a distance of 1000 meters from the village.

The fight for the village endures two days and nights. We have a tough time of it until we succeed in pushing the Soviets back. On the third day the HKL [

Hauptkampflinie

—main front line] has been reestablished. And at the same time, the civilians return, friendly and innocently smiling like children as if nothing had happened.

The bullet-riddled windows have been repaired, the damaged walls have been covered and the shredded roofs have been resealed. Babushka, Matka, and the children work from dawn to dusk. In the evening the large family sits around the stove or lies on the floor. At the edge of the village is our ammunition depot. While this is not the best, it isn’t a problem since Ivan has not paid us a visit for long time and it is very well camouflaged. The snow is already very soft, but the wind is still icy. At night we sink into our straw beds totally exhausted. Again, like the other nights, we yearn for our Russian hosts to retire so that we can get a good night’s sleep on our straw mats. But nobody moves. We try to hide our heads in the pillows. During the afternoon our hosts stayed in the sticky but warm huts. Later on they disappeared with their wives and kids into the potato storage. When we found them, they were grinning sheepishly, but did not talk to us.

We finally get our rest and swear that we will shoot anybody who disturbs our sleep. Suddenly we wake up. Fragments from the window are lying on my body; glass shards and debris is everywhere, and near the stove a palm-sized splinter is sticking out of the clay wall. And now it is rumbling and cracking everywhere. Ivan’s airplanes fly until two in the morning. I count 53 bomb explosions. One-third of the village is destroyed by the time they left. But at least they did not succeed in hitting our ammunition depot, which would have flattened the entire village.

In the morning the entire clan appears again and repairs their houses yet again as good as possible. For three more nights they continue to sleep on the oven, only to disappear later again in the potato storage. Meanwhile, we catch on to what they are doing. We pack our belongings and also seek cover in the sticky potato holes.

Tonight the Russian bombers return once again and destroy half the remaining village. The rest is smashed to smithereens from the exploding ammunition depot. Once again the Russian civilians were better informed. They have their own underground communication network with the Russian front. Our GFP [secret field police] tried very hard to crack their communications system. But it was futile!

I have been standing on the road to the front for hours, waiting to guide the trucks into their positions. Platoons are pushing forward, the artillery rumbles by; the ground vibrating from the grinding wheels. To my rear I can see the flickering glow of cigarettes. My spade bangs against my gas mask at every step. A horseback rider gallops forward. Somebody asks what time it is: it’s two in the morning. A canteen nearby is brewing fresh tea. The smell of tea with rum wafts over the road. Cooking utensils are rattling. Ahead of us is a thundering noise, sheet lightning illuminates the sky—the muzzle flash of the heavy artillery. In between is the tak-tak-tak hammering of machine guns, just like the second hand of a pocket watch. Finally at three in the morning our platoon trucks arrive, which had been delayed due to attacks by

Ivan

.

After a peaceful cigarette we advance. The road gets worse and worse, strewn with potholes.

In Mattuoje we come upon the firing zone. The impacts are now close to our road. Vehicles are rushing back. Somebody shouts from the last vehicle: “The ammunition truck has been hit!” At the edge of the village is a bright, darting flame which illuminates the trajectory of the enemy artillery. Now it is getting serious. Somebody shouts: “Stop! More fire! Take cover!” The ground trembles from the multiple dull thuds. We cling to the ground as if it could provide us with protection. Splinters are buzzing and whirring by, only to be interrupted by the dull thuds in the distance, the shots from the next round. But we have to advance. Our platoon has to be in position by morning.