Bury My Heart at Wounded Knee (36 page)

Read Bury My Heart at Wounded Knee Online

Authors: Dee Brown

Having been around the Kansas forts enough to know the prejudices of white men, Satanta held his temper. He did not want his people destroyed as Black Kettle’s had been. The parley began coldly, with two interpreters attempting to translate the exchange of conversation. Realizing the interpreters knew fewer words of Kiowa than he knew of English, Satanta called up one of his warriors, Walking Bird, who had acquired a considerable vocabulary from white teamsters. Walking Bird spoke proudly to Custer, but the soldier chief shook his head; he could not understand the Kiowa’s accent. Determined to make himself understood, Walking Bird went closer to Custer and began stroking his arm as he had seen soldiers stroke their ponies. “Heap big nice sonabitch,” he said. “Heap sonabitch.”

2

Nobody laughed. The interpreters finally made Satanta and Lone Wolf understand that they must bring their Kiowa bands into Fort Cobb or face destruction by Custer’s soldiers. Then, in violation of the truce, Custer suddenly ordered the chiefs and their escort party put under arrest; they would be taken to Fort Cobb and held as prisoners until their people joined them there. Satanta accepted the pronouncement calmly, but said he would have to send a messenger to summon his people to the fort. He sent his son back to the Kiowa villages, but instead of ordering his people to follow him to Fort Cobb, he warned them to flee westward to the buffalo country.

Each night as Custer’s military column was marching back to Fort Cobb, a few of the arrested Kiowas managed to slip away. Satanta and Lone Wolf were too closely guarded, however, to make their escapes. By the time the Bluecoats reached the fort, the two chiefs were the only prisoners left. Angered by this, General Sheridan declared that Satanta and Lone Wolf would be hanged unless all their people came into Fort Cobb and surrendered.

This was how by guile and treachery most of the Kiowas were forced to give up their freedom. Only one minor chief, Woman’s Heart, fled with his people to the Staked Plains, where they joined their friends the Kwahadi Comanches.

To keep close watch upon the Kiowas and Comanches, the Army built a new soldier town a few miles north of the Red River boundary and called it Fort Sill. General Benjamin

Grierson, a hero of the white man’s Civil War, was in command of the troops, most of them being black soldiers of the Tenth Cavalry. Buffalo soldiers, the Indians called them, because of their color and hair. Soon an agent with no hair on his head arrived from the East to teach them how to live by farming instead of hunting buffalo. His name was Lawrie Tatum, but the Indians called him Bald Head.

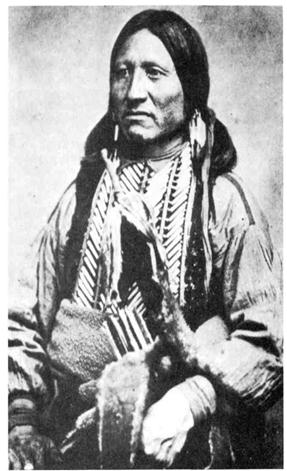

18. Satanta, or White Bear. From a photograph by William S. Soule, taken around 1870. Courtesy of the Smithsonian Institution

General Sheridan came to the new fort, released Satanta and Lone Wolf from arrest, and held a council in which he scolded the chiefs for their past misdeeds and warned them to obey their agent.

“Whatever you tell me,” Satanta replied, “I mean to hold fast to. I will pick it up and hold it close to my breast. It don’t alter my opinion a particle if you take me by the hand now, or take and hang me. My opinion will be just the same. What you have told me today has opened my eyes, and my heart is open also. All this ground is yours to make the road for us to travel on. After this, I am going to have the white man’s road, to plant corn and raise corn. … You will not hear of the Kiowas killing any more whites. … I am not telling you a lie now. It is the truth.”

3

By corn-planting time, two thousand Kiowas and twenty-five hundred Comanches were settled on the new reservation. For the Comanches there was something ironic in the government’s forcing them to turn away from buffalo hunting to farming. The Comanches had developed an agricultural economy in Texas, but the white men had come there and seized their farmlands, forcing them to hunt buffalo in order to survive. Now this kindly old man, Bald Head Tatum, was trying to tell them they should take the white man’s road and go to farming, as if the Indians knew nothing of growing corn. Was it not the Indian who first taught the white man how to plant corn and make it grow?

For the Kiowas it was a different matter. The warriors looked upon digging in the ground as women’s work, unworthy of mounted hunters. Besides, if they needed corn they could trade pemmican and robes to the Wichitas for corn, as they had always done. The Wichitas liked to grow corn, but were too fat and lazy to hunt buffalo. By midsummer the Kiowas were

complaining to Bald Head Tatum about the restrictions of farming. “I don’t like corn,” Satanta told him. “It hurts my teeth.” He was also tired of eating stringy Longhorn beef, and he asked Tatum for an issue of arms and ammunition so the Kiowas could go on a buffalo hunt.

4

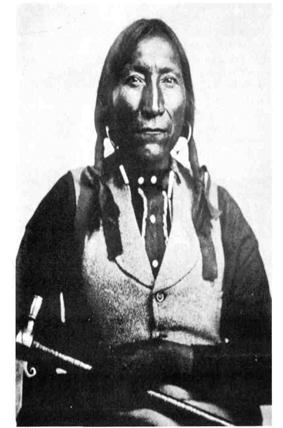

19. Lone Wolf, or Guipago. Photographed by William S. Soule sometime between 1867 and 1874. Courtesy of the Smithsonian Institution.

That autumn the Kiowas and Comanches harvested about four thousand bushels of corn. It did not last long, distributed among 5,500 Indians and several thousand ponies. By springtime of 1870 the tribes were starving, and Bald Head Tatum gave them permission to go on a buffalo hunt.

In the Summer Moon of 1870, the Kiowas held a big sun dance on the North Fork of Red River. They invited the Comanches and Southern Cheyennes to come as guests, and during the ceremonies many disillusioned warriors talked of staying out on the Plains and living in plenty with buffalo instead of returning to the reservation for meager handouts.

Ten Bears of the Comanches and Kicking Bird of the Kiowas spoke against this talk; they thought it best for the tribes to continue taking the white man’s hand. The young Comanches did not condemn Ten Bears; after all, he was too old for hunting and fighting. But the young Kiowas scorned Kicking Bird’s counsel; he had been a great warrior before the white men penned him up on the reservation. Now he talked like a woman.

As soon as the dancing was finished, many of the young men rode off to Texas to hunt buffalo and raid the Texans who had taken their lands. They were especially angry against white hunters who were coming down from Kansas to kill thousands of buffalo; the hunters took only the skins, leaving the bloody carcasses to rot on the Plains. To the Kiowas and Comanches the white men seemed to hate everything in nature. “This country is old,” Satanta had scolded Old Man of the Thunder Hancock when he met him at Fort Larned in 1867. “But you are cutting off the timber, and now the country is of no account at all.” At Medicine Lodge Creek he complained again to the peace commissioners: “A long time ago this land belonged to our fathers; but when I go up to the river I see camps of soldiers here on its banks. These soldiers cut down my timber; they kill my buffalo; and when I see that, my heart feels like bursting; I feel sorry.”

5

Through that Summer Moon of 1870, the warriors who stayed

on the reservation taunted Kicking Bird unmercifully for advocating farming instead of hunting. At last Kicking Bird could bear no more. He organized a war party and invited his worst tormentors—Lone Wolf, White Horse, and old Satank—to accompany him on a raid into Texas. Kicking Bird did not have the bulky, muscular body of Satanta. He was slight and sinewy and light-skinned. He may have been sensitive because he was not a full-blooded Kiowa; one of his grandfathers had been a Crow Indian.

With a hundred warriors at his back, Kicking Bird crossed the Red River boundary and deliberately captured a mail coach as a challenge to the soldiers at Fort Richardson, Texas. When the Bluecoats came out to fight, Kicking Bird displayed his skill in military tactics by engaging the soldiers in a frontal skirmish while he sent two pincer columns to strike his enemy’s flanks and rear. After mauling the troopers for eight hours under a broiling sun, Kicking Bird broke off the fight and led his warriors triumphantly back to the reservation. He had proved his right to his chieftaincy, but from that day he worked only for peace with the white man.

By the coming of cold weather, many roving bands were back in their camps near Fort Sill. Several hundred young Kiowas and Comanches, however, remained on the Plains that winter. General Grierson and Bald Head Tatum scolded the chiefs for raiding in Texas, but they could say nothing against the dried buffalo meat and robes which the hunters brought back to help see their families through another season of scanty government rations.

Around the Kiowa campfires that winter there was much talk about the white men who were pressing in from all four directions. Old Satank was grieving for his son, who had been killed that year by the Texans. Satank had brought back his son’s bones and placed them upon a raised platform inside a special tepee, and now he always spoke of his son as sleeping, not as dead, and every day he put food and water near the platforms so that the boy might refresh himself on awakening. In the evenings the old man sat squinting into the campfires, his bony fingers stroking the gray strands of his moustache. He seemed to be waiting for something.

Satanta moved restlessly about, always talking, making proposals to the other chiefs as to what they should do. From everywhere they heard rumors that steel tracks for an Iron Horse were coming into their buffalo country. They knew that railroads had driven the buffalo from the Platte and the Smoky Hill; they could not permit a railroad through their buffalo country. Satanta wanted to talk to the officers at the fort, convince them that they should take the soldiers away and let the Kiowas live as they had always lived, without a railroad to frighten the buffalo herds.

Big Tree was more direct. He wanted to go to the fort some night, set the buildings on fire, and then kill all the soldiers as they ran out. Old Satank spoke against such talk. It would be a waste of words to talk to the officers, he said, and even if they killed all the soldiers at the fort, more would come to take their places. The white men were like coyotes; there were always more of them, no matter how many were killed. If the Kiowas wanted to drive the white men out of their country and save the buffalo, they should start on the settlers, who kept fencing the grass and building houses and making railroads and slaughtering all the wild game.

When spring came in 1871, General Grierson sent out patrols of his black soldiers to guard the fords along Red River, but the warriors were eager to see the buffalo again, and they slipped past the soldiers. Everywhere they went that summer on the Texas plains they found more fences, more ranches, and more white buffalo hunters with deadly long-range rifles slaughtering the diminishing herds.

In the Leaf Moon of that spring, some Kiowa and Comanche chiefs took a large hunting party up the North Fork of Red River, hoping to find buffalo without leaving the reservation. They found only a few, most of the herds being far out in Texas. Around the evening campfires they began talking again of how the white men, especially the Texans, were trying to drive all the Indians into the ground. Soon they would have an Iron Horse running across the prairie, and all the buffalo would disappear. Mamanti the Sky Walker, a great medicine man, suggested that it was time for them to go down to Texas and start driving the Texans into the ground.