Blood Brotherhoods (55 page)

Read Blood Brotherhoods Online

Authors: John Dickie

The legacy of the

Risorgimento

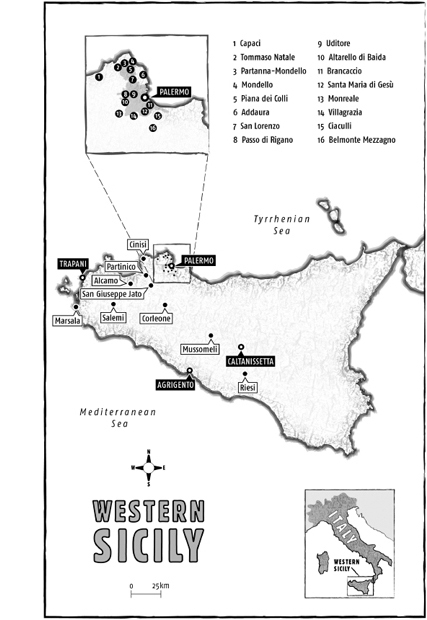

in parts of the South and Sicily was a sophisticated and powerful model of criminal organisation. The members of these brotherhoods deployed violence for three strategic purposes. First: to control other felons, to farm them for money, information and talent. Second: to leech the legal economy. And third: to create contacts among the upper echelons—the landowners, politicians and magistrates. In the environs

of Palermo the mafia, boosted by the island’s recent history of revolution, did not just have contacts with the upper class, it formed an integral facet of the upper class.

The new Kingdom of Italy failed to address that legacy. Worse, it lapsed into sharing its sovereignty with the local bosses. Italy allowed a criminal ecosystem to develop. It tried to live out the dream of being a modern state; but it did so with few of the resources that its wealthier neighbours could draw on, and with many more innate disadvantages. The result was political fragmentation and instability: an institutional life driven less by policies designed to address collective problems than by haggling for tactical advantage and short-term favours. This was a political system that frequently gave leverage to the worst pressure groups in the country—the ones sheltering men of violence. At election time the government sometimes used gangsters to make sure the right candidates won. Parliament produced bad legislation, which was then selectively enforced: the practice of dealing with

mafiosi

and

camorristi

by sending them into ‘enforced residence’ is one prime instance. Urgently needed reforms never materialised: an example being the utter legislative void around the likes of Calogero Gambino (from the ‘fratricide’ case of the 1870s) and Gennaro Abbatemaggio (from the Cuocolo trial of the early 1900s)—

mafiosi

and

camorristi

who abandoned the ranks of their brotherhoods and sought refuge with the state. Italy also had enough lazy and cynical journalists, wrong-headed intellectuals and morally obtuse writers to mask the real nature of the emergency, give resonance and credibility to the underworld’s own twisted ideology, and allow gangsters to gaze at flattering reflections of themselves in print.

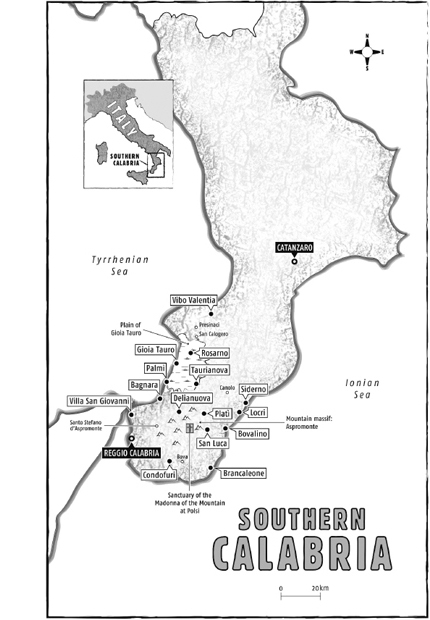

The criminal ecosystem spawned a new Honoured Society, the picciotteria, to retrace the evolutionary path of its older cousins: in the 1880s, it quickly progressed from prison to achieve territorial dominance in the outside world.

Yet to say that Italy harboured a criminal ecosystem is not to say that the country was run by gangsters. Italy has never been a failed state, a mafia regime. The reason why the mafias of southern Italy and Sicily have such a long history is

not

because they were and are all-powerful, even in their heartlands. The rule of law was not a dead letter in the peninsula, and Italy

did

fight the mafias.

Omertà

broke frequently. Sometimes the mafias’ territorial control broke too, leading to a reawakening in what good police like Ermanno Sangiorgi called the

spirito pubblico

—the ‘public spirit’: in other words, the belief that people could trust the state to enforce its own rules. Such moments offered a glimpse of an underlying public hunger for legality, and showed what could have been achieved had there been a more consistent anti-mafia effort.

But alas, Italy fought the Honoured Societies only for so long as their overt violence kept them at the top of the political agenda. It fought them only until the mafias’ wealthy and powerful protectors could exert an influence. It fought them only enough to sharpen the gangster domain’s internal process of natural selection. Over the years, weaker bosses and dysfunctional criminal methodologies were weeded out. Hoodlums were obliged to change and develop. The Sicilian mafia had the least to learn. In Naples, the Honoured Society failed to learn enough. Perhaps against the odds, the Calabrian picciotteria, that working museum of the oldest traditions of the prison camorras, proved itself capable of adapting to survive and grow.

In the underworld competition not just to dominate, but to endure, the mafias found perhaps their most important resource in family. Through their kin,

mafiosi, camorristi

and

picciotti

gained their strongest foothold in society, the first vehicle for their pernicious influence. Thus the lethal damage that the mafias caused to so many families—their own and their victims’—is the most poignant measure of the evil they did.

From 1925 Benito Mussolini styled his regime as the antithesis of the squalid politicking of the past, the cure for Italy’s weak-willed concessions to the gangs. But Fascism ended up repeating many of the mistakes committed during earlier waves of repression. The same short attention span. The same reliance on ‘enforced residence’. The same reluctance to prosecute the mafias’ protectors among the elite. The same failure to tackle the endemic mafia presence in the prisons. Political internees in the 1920s and 1930s told

exactly

the same stories of mob influence behind bars as poor Duke Sigismondo Castromediano and the other patriotic prisoners of the

Risorgimento

had done three generations earlier.

The only thing that Mussolini did markedly better than his liberal predecessors was to pump up the publicity and smother the news. With a little help from the Sicilian mafia, he created the lasting illusion that Fascism had, at the very least, suppressed the mob. So when it came to organised crime, Fascism’s most harmful legacy was its determination to keep quiet about the problem. The

Zone Handbooks

with which the Allied forces arrived in Sicily, Calabria and Campania accurately reflect the desperately limited state of public knowledge that Fascism bequeathed. (They were based on published Italian sources after all.)

Fascism’s legacy was indeed a damaging one. Amid the chaos of war and Liberation, the country was immediately faced with the reality of endemic criminal power that lay behind the dumb bluster of the regime’s propaganda.

When the Second World War ended, Italy quickly became a democracy. Not long afterwards, it would develop into a major industrial power. Here was a very different country from the

Italietta

—the ‘mini Italy’—that had

first confronted the mafias after 1860, or from the deluded, strutting Italy of the Blackshirt decades. The transition of 1943–48 was the most profound in the country’s entire history: from war to peace; from dictatorship to freedom. Yet some things about Italy did not change—and the history of organised crime in the post-war period is the most disturbing measure of the continuities. The same political vices that had helped give birth to the mafias would propel them to even greater power and violence during the era of democracy and prosperity. After 1945, just as it had done since 1860, Italy’s political class settled into a messy accommodation with the mob.

Fascism can be blamed for many things, but certainly not for that accommodation. The

Zone Handbooks

did not represent the full extent of the knowledge about the mafias that Mussolini’s regime bequeathed. The police and magistrates who had spent much of the 1920s and 1930s fighting organised crime knew exactly how dangerous the gangland organisations of Campania, Calabria and Sicily were: theirs was a bank of experience and understanding from which a fledgling post-Fascist Italy had a great deal to learn. Yet almost everything they knew was ignored or repressed. The new Italian state proved itself more reluctant than Fascism to stand up to the mafias, and even keener than Fascism to unlearn the lessons of the past. Once the Second World War was over, mafia history began all over again—with an act of forgetting.

S

ICILY

: Banditry, land and politics

T

ODAY

’

S

I

TALY CAME INTO BEING ON

2

AND

3 J

UNE

1946,

WHEN A PEOPLE BATTERED BY

war voted in a referendum to abolish a monarchy that had been profoundly discredited by its subservience to Fascist dictatorship. Here was a clean break with the past: Italy would henceforth be a Republic. In the same poll, Italians elected the members of a Constituent Assembly who were charged with drafting a new constitution for the Republic based on democracy, freedom and the rule of law.

The camorra, the ’ndrangheta and Cosa Nostra are a monstrous insult to the Italian Republic’s founding values—the same values that underpin Italy’s, and Europe’s, post-war prosperity. But in Italy, alone among Western European nations, mafia power has been perfectly compatible with the day-to-day reality of freedom, democracy and prosperity. The story of how that happened began as soon as Italy embarked on the difficult transition from war to peace.

AMGOT came to an end in February 1944: Sicily and much of the South came under the authority of the coalition of anti-Fascist forces making up the new civilian government. So it was southerners, people from the traditional heartlands of organised crime, who were the first Italians to reacquire the power to shape the country’s future. The path towards that future was marked by four milestones: