Another Insane Devotion (4 page)

Read Another Insane Devotion Online

Authors: Peter Trachtenberg

She said, “I just don't like to be touched like that. I don't know you.” Then she left.

Afterward, it seemed to me that I'd been exposed to two completely different personalities. One was magnanimous; the other was grudging. One would repay ostracism with magic Beatle dolls; the other recoiled from a touch. One was deeply attuned to other people's desires; the other was almost oblivious to them, or at least oblivious to the desire for forgiveness of someone who'd committed a minor social error (at least I thought it was minor; it wasn't as if I'd done what a friend of mine, a singer, had once had done to her by a guy she met at one of her gigs. “I really like the way you sing,” he'd told her when she sat down with him during the break. “It came right from the clit.” And by way of illustration, he reached for it). The alternation between these personalities was so shocking that my automatic response was to label one as the real F. and the other a false self, a facade, a cutout. And for the rest of that night and many nights afterward, I occupied myself trying to figure out which was which. If the true self is the one that's

most readily evident to an observer, then the true F. was the watchful, defensive one, her gaze unblinking, her soft features impassive. If the true self is the one that's kept tucked away like a hole card, the true F. was the one who beamed as she gave treasure to traducers.

most readily evident to an observer, then the true F. was the watchful, defensive one, her gaze unblinking, her soft features impassive. If the true self is the one that's kept tucked away like a hole card, the true F. was the one who beamed as she gave treasure to traducers.

I know this episode doesn't say much about her. She likes tea, not coffee, or liked it then, with milk and lots of sugar. As a child, she experienced displacement and the cruelty of her peers and responded with generosity, at least in her imagination. (If it had been my imagination, I would've been wiping the floor with those boys and making the girls fall grovelingly in love with me so I could reject them.) She doesn't like strangers touching her. It's all I can say. There's only so much you can say about a wife.

Here a few punch lines suggest themselves:

“I mean to her face.”

“Unless she's

your

wife.”

your

wife.”

“If you want to keep her.”

Baddabing.

Marriage accommodates all sorts of betrayals. It is, in a sense, betrayal's dedicated environment, a hot air balloon whose skin is so easily punctured by the pointy accessories of its passengers, a high-heeled shoe, a tiepin, a toothpick. I may not know if I want to keep my wife, but I don't want to betray her, or at least not her privacy, considering that her sense of privacy is essentially what caused her to flinch when I first tried to touch her face. A person is a laminated entity, and the body is only one of its layers. It may not be the most intimate one. There are beaches where peopleânot even very good-looking peopleâ

promenade on the dunes gaily displaying their genitals like designer purses. There are rooms where strangers proclaim their secrets to each other in voices choked with snot and tears: they pay money for this. The appeal of these practices is the appeal of divestiture, a word that comes from the Latin for “to take off clothing.” They're supposed to make you feel lighter, though clothing doesn't weigh very much and secrets weigh nothing at all. In an attempt to combine the two kinds of divestiture, F. and I once imagined a therapeutic retreat where people would strip naked and partner up, with one partner lying on her (or his) back with her (or his) feet clasped in the yoga position known as the “Happy Baby,” while the other peered studiously into the body cavities thus exposed with the aid of a flashlight and magnifying glass. “Intimacy,” the group leader would croon, “means âinto-me-see.'”

promenade on the dunes gaily displaying their genitals like designer purses. There are rooms where strangers proclaim their secrets to each other in voices choked with snot and tears: they pay money for this. The appeal of these practices is the appeal of divestiture, a word that comes from the Latin for “to take off clothing.” They're supposed to make you feel lighter, though clothing doesn't weigh very much and secrets weigh nothing at all. In an attempt to combine the two kinds of divestiture, F. and I once imagined a therapeutic retreat where people would strip naked and partner up, with one partner lying on her (or his) back with her (or his) feet clasped in the yoga position known as the “Happy Baby,” while the other peered studiously into the body cavities thus exposed with the aid of a flashlight and magnifying glass. “Intimacy,” the group leader would croon, “means âinto-me-see.'”

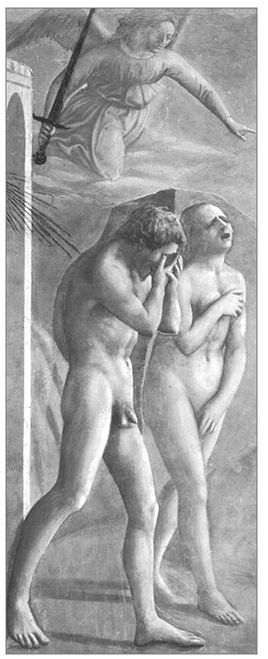

To me the definitive image of nakedness has always been Masaccio's

The Expulsion of Adam and Eve from the Garden of Eden

. The Adam and Eve depicted in it don't look light. Adam's back is bowed. Eve is covering her breasts and sex. She doesn't do this like someone shielding herself from a lustful gaze; she covers them the way one covers a wound. Curiously, Masaccio's Adam doesn't cover his parts but his face, as people do when they weep. Even children do this, from a very young age. I think of these two figures as personifying two kinds of violated privacy, the privacy of the body and the privacy of the soul.

The Expulsion of Adam and Eve from the Garden of Eden

. The Adam and Eve depicted in it don't look light. Adam's back is bowed. Eve is covering her breasts and sex. She doesn't do this like someone shielding herself from a lustful gaze; she covers them the way one covers a wound. Curiously, Masaccio's Adam doesn't cover his parts but his face, as people do when they weep. Even children do this, from a very young age. I think of these two figures as personifying two kinds of violated privacy, the privacy of the body and the privacy of the soul.

The soul is often thought of as residing in the eyes. “I looked into his eyes and saw his soul,” George W. Bush said after meeting the Russian premier. Proust is more long-winded, though his long-windedness is dictated by precision. He calls

the eyes “those features in which the flesh becomes a mirror and gives us the illusion that it allows us, more often than through other parts of the body, to approach the soul.”

the eyes “those features in which the flesh becomes a mirror and gives us the illusion that it allows us, more often than through other parts of the body, to approach the soul.”

Â

Masaccio,

The Expulsion of Adam and Eve from The Garden of Eden

(1426â1428), Cappella Brancacci, Santa Maria del Carmine. Courtesy of the Granger Collection.

The Expulsion of Adam and Eve from The Garden of Eden

(1426â1428), Cappella Brancacci, Santa Maria del Carmine. Courtesy of the Granger Collection.

F. and I went to see the

Expulsion

a few years ago in Florence. It was July, a terrible time to be there, so hot we had only to step out of the hotel to feel the air being sucked from our lungs, and verminous with tourists. We were part of that vermin. We walked for many hours, uncomplainingly, down narrow streets, past shops selling gold-stamped leather goods or old maps or ice cream. Every so often we'd enter a square where a crowd milled around a gigantic dome like an ant colony around a fallen sugar bun. The

Expulsion

was located in the Church of Santa Maria del Carmine. It was part of a sequence of frescoes Masaccio had painted in the Brancacci Chapel. A few feet away people were praying. My wife was surprised by that. She hadn't been in many churches before, and not until she came to Italy had she been in one where the cults of God and art were

worshipped side by side with no apparent friction between their adherents. The art viewers stood, talking in (mostly) low voices; the churchgoers sat in silence. We looked at the painting. The bowed figures seemed small, humble, two ordinary humans who, out of a momentary desire, a whim, had tripped the switch of the doomsday machine of sin and death. Adam's body was the body of the laborer he would become, condemned to wrest his food from the earth and eat it salted with sweat and tears. Eve had the spreading hips and drooping breasts of someone who has already borne children. In Genesis this doesn't happen until after the expulsion; the expulsion is the first punishment. But my guess is that Masaccio wanted viewers to see the full consequences of that first act of disobedience, and so he had shown Adam and Eve stumbling out of paradise, shamefaced and weeping, their flesh already marked with their sin.

Expulsion

a few years ago in Florence. It was July, a terrible time to be there, so hot we had only to step out of the hotel to feel the air being sucked from our lungs, and verminous with tourists. We were part of that vermin. We walked for many hours, uncomplainingly, down narrow streets, past shops selling gold-stamped leather goods or old maps or ice cream. Every so often we'd enter a square where a crowd milled around a gigantic dome like an ant colony around a fallen sugar bun. The

Expulsion

was located in the Church of Santa Maria del Carmine. It was part of a sequence of frescoes Masaccio had painted in the Brancacci Chapel. A few feet away people were praying. My wife was surprised by that. She hadn't been in many churches before, and not until she came to Italy had she been in one where the cults of God and art were

worshipped side by side with no apparent friction between their adherents. The art viewers stood, talking in (mostly) low voices; the churchgoers sat in silence. We looked at the painting. The bowed figures seemed small, humble, two ordinary humans who, out of a momentary desire, a whim, had tripped the switch of the doomsday machine of sin and death. Adam's body was the body of the laborer he would become, condemned to wrest his food from the earth and eat it salted with sweat and tears. Eve had the spreading hips and drooping breasts of someone who has already borne children. In Genesis this doesn't happen until after the expulsion; the expulsion is the first punishment. But my guess is that Masaccio wanted viewers to see the full consequences of that first act of disobedience, and so he had shown Adam and Eve stumbling out of paradise, shamefaced and weeping, their flesh already marked with their sin.

I turned to point this out to F., but she'd left my side. I found her in one of the pews, sitting with her hands folded in her lap. “What are you doing?” I asked her. She said, “I'm praying.” Then she asked, “Do you want to pray with me?” I said yes. I did as well as I was able. The walls of the chapel were pale gray marble or granite; light seemed to dwell beneath their surface. I stole a glance at my wife. She was looking straight ahead, and in profile I could see that her eyes were deeply sunken. That always happens when she's upset. I knew what she was praying for. She was praying for a cat.

The first person I called after hanging up on Bruno was Sherri, who usually watched the cats for us when we went away. I felt

sheepish, considering that I was asking her for help finding the cat the kid we'd hired in her place had lost. I might have explained that the only reason we'd done that was because at twenty bucks a visit we couldn't afford to hire her for an entire month, but then she could have reminded me that you get what you pay for. However, she was gracious. She doubted Biscuit had gone very far. She was a bright animal who knew where her Friskies were dished out, and she was probably just wandering around the property, sheltering beneath the eaves of the barn when it got too wet. Sherri said she'd come over and help look for her. In the meantime, Bruno should be sure to call Biscuit from different locations on the property, not just from the porch but from the driveway and the front door and the toolshed out back, and leave out a bowl of food to remind her that home was where good things came from. I phoned Bruno to repeat these instructions, but he didn't pick up. Maybe he was still outside, calling, “Biscuit, Biscuit, Biscuit!” in the rain. Maybe he'd turned off his phone.

sheepish, considering that I was asking her for help finding the cat the kid we'd hired in her place had lost. I might have explained that the only reason we'd done that was because at twenty bucks a visit we couldn't afford to hire her for an entire month, but then she could have reminded me that you get what you pay for. However, she was gracious. She doubted Biscuit had gone very far. She was a bright animal who knew where her Friskies were dished out, and she was probably just wandering around the property, sheltering beneath the eaves of the barn when it got too wet. Sherri said she'd come over and help look for her. In the meantime, Bruno should be sure to call Biscuit from different locations on the property, not just from the porch but from the driveway and the front door and the toolshed out back, and leave out a bowl of food to remind her that home was where good things came from. I phoned Bruno to repeat these instructions, but he didn't pick up. Maybe he was still outside, calling, “Biscuit, Biscuit, Biscuit!” in the rain. Maybe he'd turned off his phone.

I don't remember whom else I phoned that evening, only that I mostly stayed in the kitchen, gazing out the window into the yard. Once or twice I stepped out onto the deck to pace until the rainâfor it was raining where I was tooâforced me back inside. I couldn't stay still, but I didn't want to go anywhere else in the house. It would mean losing sight of the big live oak and the beds of modest, garden-variety flowers and the lawn I clipped with a rickety mechanical push mower whose unamplified whirr was so much more pleasing than the engorged growl of the Sears Craftsman I used up north. I kept the deck lights on. I often saw cats sunning themselves in the yard, and maybe

on some unconscious level, I thought that if I waited long enough, I would see Biscuit there too.

on some unconscious level, I thought that if I waited long enough, I would see Biscuit there too.

I don't remember Bitey going into heat, only bringing her back from the vet after she'd been spayed. She was so listless I had to scoop her out of the carrier. She rose unsteadily and looked about her, then drank a little water before stumbling off to the spot by the radiator where she liked to sleep. I watched her through the day. Did she always sleep this long? Did her stomach look swollen, or was that just because it was shaved? (The awful nakedness of a cat's shaved stomach!) Shouldn't she be drinking more? I was used to sick people. All through my teens my mother and grandfather took turns trooping in and out of the hospital like the allegorical figures in those clocks you see looming over town squares all over Germany. I once saw one whose automata included Death, gliding out in his black shroud, wielding his scythe with a jerk. But sick people can tell you what's wrong with them, more or less, and what they want. Sick animals can't. You have to read them. You lean over them as you would lean over a book, gauging the rise and fall of their breath, the luffing of a ribcage, a wheeze, a sigh, the twitch of a lip. Of course, Bitey wasn't sick then, just postoperative, and a day later she was eating normally and chasing wads of cellophane around the living room.

She seemed not to miss her uterus, no more than Ching, the stripy male I got to keep her company a year later, seemed to miss his balls after they were snipped off. The night before his procedure, Bitey wrestled him onto his back and began

roughly grooming him. (Felinologists call this behavior al-logrooming and identify it with dominance. You can spot the top cat in any colony by seeing which one most frequently grooms the others.) At one point it looked as if she was about to lick his genitals, but he pushed her away with his forepaws like someone trying to hold a door shut against the pounding of housebreakers. “Don't stop her, you fool!” I yelled at him. “It's your last chance!” It was no use; it might not have been even if he'd had an inkling of what I was yelling about.

roughly grooming him. (Felinologists call this behavior al-logrooming and identify it with dominance. You can spot the top cat in any colony by seeing which one most frequently grooms the others.) At one point it looked as if she was about to lick his genitals, but he pushed her away with his forepaws like someone trying to hold a door shut against the pounding of housebreakers. “Don't stop her, you fool!” I yelled at him. “It's your last chance!” It was no use; it might not have been even if he'd had an inkling of what I was yelling about.

Other books

GAY REALITY : THE TEAM GUIDO STORY by John Chaffetz

Long Hair Styles by Limon, Vanessa

The Lady Next Door by Laura Matthews

The Operator (Bruce and Bennett Crime Thriller 2) by Laws, Valerie

The Spiral Effect by James Gilmartin

Relativity by Lauren Dodd

The Old American by Ernest Hebert

The Alaskan Adventure by Franklin W. Dixon

La Raza Cósmica by Jose Vasconcelos

Gangster by John Mooney