American Crucifixion (9 page)

Read American Crucifixion Online

Authors: Alex Beam

JOSEPH WORKED IN THE STORE, AND AFTER 1843 HE LIVED IN THE stately Nauvoo Mansion, a two-story L-shaped building at the intersection of Sidney (as in Rigdon) and Main Streets. The mansion had seventeen rooms, many of them rented out to tourists or transients, and boasted the largest stable in Illinois, a brick structure large enough to hold seventy-five horses. There was a cannon mounted in the front yard, and the premises were often under guard, as Joseph feared process servers or Missouri bounty hunters invading his home.

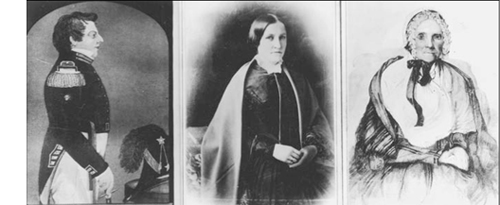

Joseph Smith, Emma Smith, and Joseph’s mother, Lucy Mack Smith, who lived with them in Nauvoo.

Credit: Utah State Historical Society

Joseph and Emma employed considerable live-in help: an African American washerwoman named Jane Manning and a cook, as well as serving girls to help in the dining room. (Manning, who would later join the Mormon migration to Utah, was one of about forty free blacks living in Nauvoo.) At banquets, it was not uncommon for Joseph and Emma to help serve guests themselves, aided by the young women domiciled at the Nauvoo Mansion. The mansion girls performed household chores in return for room and board. The teenage women—Sarah and Maria Lawrence, Emily and Eliza Partridge, and Lucy Walker—proved to be a temptation too great for Joseph to resist. Having covertly introduced his revelation on polygamous marriage in 1843, he ended up marrying them all, and the ensuing opéra bouffe opening and closing of bedroom doors tormented his long-suffering wife Emma.

The mansion was Emma’s home, too, and in addition to being a hotel, it was where she raised her four children, one of them an adopted daughter. Her oldest son, Joseph, a small boy during the Nauvoo years, remembered her traveling to St. Louis to buy furniture, curtains, linen, and dishes for the newly opened mansion. “When she returned,” her son wrote, “Mother found installed in the keeping-room of the hotel . . . a fully equipped tavern bar, and Porter Rockwell in charge as tender.”

She sent Joseph III to find his father. “Joseph,” she asked her husband. “What is the meaning of that bar in this house?”

Joseph explained that his friend had just been freed from a Missouri jail, and planned to open up a combination bar and barber shop across the street. The mansion tavern arrangement was purely temporary, he said.

It proved to be very temporary indeed. “How does it look for the spiritual head of a religious body to be keeping a hotel in which a room is fitted out as a liquor-selling establishment?” Emma asked. “Either that bar goes out of the house, or we will!”

Inside both his homes, first in the rustic log cabin and then at the Nauvoo Mansion, Joseph installed hiding places to provide refuge from unwanted visitors. In his first house, there was a hinged portion of the staircase leading to the cellar. Lifting the trick stairs led to “a vaulted place . . . large enough for a couple of people to occupy, either sitting or lying down, affording a degree of comfort for a stay of long or short duration as necessary,” Joseph Smith III recalled. The mansion had a garret apartment accessible from a false-backed closet built flush to one of the chimneys. If one pulled down a rack of clothespins on the back of the closet, a small staircase leading to the attic came into view. Joseph III remembered when some “so-called officials from Missouri seeking to arrest [his father] on trumped-up charges” dropped by the family home, unannounced. “Suddenly, Father and the friend who was with him disappeared,” the son remembered, “and when the men came in they found the household quietly engaged in its customary affairs.

Questioned, Mother said her husband had been there a little while before but was not there then. She invited them in to assure themselves of the fact. They made a thorough search but failed to find him.

Young Joseph, who could not have been more than ten years old at the time, confessed that he was “puzzled” by his father’s disappearance. Later, he understood that his father had melted away to the third-floor oubliette. “The suspicions of the manhunters were disarmed, and they went off about their business, leaving Father and his friend to breathe freely again.”

WHEN HE FOUND THE TIME, JOSEPH WELCOMED VISITORS AND curiosity seekers to his “heavenly city,” often escorting them up Hyde Street—most of the boulevards bore the names of prominent Saints—to his mother’s home. Lucy Mack Smith, now in her sixties, controlled access to a collection of Egyptian mummies and scrolls renowned up and down the Mississippi and even further afield. There was a sign nailed to a board in front of Mrs. Smith’s house:

EGYPTIAN MUMMIES EXHIBITED,

AND ANCIENT RECORDS EXPLAINED.

PRICE TWENTY-FIVE CENTS.

The mummies and the papyri, or “ancient records” were a highlight of any Nauvoo tour. Joseph sometimes told visitors that his mother had purchased the collection for $6,000. In fact, he had bought them himself for $2,400 from an itinerant showman who brought his artifacts to Kirtland, Ohio, in 1833. The mummies, “frightfully disfigured, and, in fact, most disgusting relics of mortality,” according to the visiting Anglican minister Henry Caswall, were apparently genuine. Their identities, as the Smiths explained them, were probably spurious.

After leading Charlotte Haven, a visitor from Portsmouth, New Hampshire, “up a short, narrow stairway to a low dark room under a roof,” Mrs. Smith held her candle up to a row of yellowing corpses. Lucy introduced her desiccated charges as the Egyptian “King Onitus and his royal household:” two wives, and the daughter of a fellow king. (Joseph told visitors the king was “Pharaoh Necho.”) For Charlotte, Mrs. Smith brandished what “seemed to be a club wrapped in a dark cloth, and said ‘This is the leg of Pharaoh’s daughter, the one that saved Moses.’” To yet another visitor, the young Eudocia Baldwin, Mrs. Smith (“a trim looking old lady in black silk gown and white cap and kerchief”) introduced the mummies as “the old King Pharaoh of the Exodus himself, with wife and daughter.” “My Son Joseph Smith has recently received a revelation from the Lord in regard to these people and times,” Mrs. Smith said, “and

he

has told these things to

me.

”

he

has told these things to

me.

”

The papyri were equally problematic. Joseph claimed the hieroglyphics were handwritten by Abraham, “the father of the faithful,” and bore the signatures of Moses and his older brother, Aaron. With the aid of God and a white seer stone, Joseph translated the papyri into the Book of Abraham, which purported to be a source for the Book of Genesis. His mother said the hieroglyphic scrolls were “the writing of Abraham and Isaac, written in Hebrew and Sanscrit.” Charlotte Haven pointed to a drawing of Eve being tempted by a snake standing on two legs. “But serpents don’t have legs,” the young woman remarked.

“They did before the Fall,” Lucy shot back.

Like the mummies, the papyri also appeared to be genuine Egyptian funerary relics. But they were not the “lost” book of Abraham, and they did not help explain the origins of the Negro race, as Joseph claimed. The scrolls cost the Mormons much future vexation, as they reinforced the prevalent racist doctrine that African Americans were descendants of the cursed Canaanites, the children of Noah’s son Ham.

In the 1960s, a Metropolitan Museum of Art expert uncharitably characterized Joseph’s translation of the scrolls as “a farrago of nonsense from beginning to end.”

ON MAY 15, 1844, AS HE OFTEN DID, JOSEPH SPENT THE DAY WITH two eminent visitors who hopped off the steamboat to catch a glimpse of the “bourgeois Mohammed.” The day-trippers were the young Bostonians Charles Francis Adams and Josiah Quincy, one the son of former president John Quincy Adams, and the other a future mayor of Boston. They intended “to see for ourselves the result of the singular political system which had been fastened upon Christianity,” Quincy later wrote.

Joseph was at the top of his game. He showed them the Egyptian mummies and insisted they tip his mother a quarter-dollar for the pleasure. He bragged about his extensive knowledge of ancient languages (“his miraculous gift of understanding all languages”), and of course escorted his guests to the Nauvoo Temple, “the grotesque structure on the hill,” as Quincy called it. With the Bostonians trotting behind him, Joseph roamed his domain like a feudal lord, bantering with a stonecutter at the temple, engaging in an impromptu debate with a visiting Methodist preacher, even rousting female visitors from the mansion in full view of his visitors.

Not for one second did Joseph sound like a man facing uprisings both inside and outside his Mormon kingdom. Quite the contrary, he waxed on endlessly about national politics, and about his personal quest for the presidency. Quincy tried to ask a serious question: “Is it possible that you have too much power to be safely trusted to one man?”

“In your hands, or that of any other person,” Joseph answered, “so much power would, no doubt, be dangerous. I am the only man in the world it would be safe to trust with it. Remember,”—Quincy noted that these last few words “were spoken in a rich, comical aside”—“I am a prophet!”

* Joseph Smith called Jackson “the acme of American glory,” in large part because he approved of Jackson’s brutal Indian removal policies.

Other books

Broken Lives by Brenda Kennedy

By the Book by Dean Wesley Smith, Kristine Kathryn Rusch

Fated Memories by Judith Ann McDowell

Little Amish Matchmaker by Linda Byler

The Woman from Kerry by Anne Doughty

Chasing Serenity (Seeking Serenity) by Butler, Eden

Diamonds (Den of Thieves Book 1) by Cosgrove, A.M.

Keepers of the Flame (Trilogy Bundle) by Hart, Melissa F.

Master's Submission by Harker, Helena