American Crucifixion (8 page)

Read American Crucifixion Online

Authors: Alex Beam

In the early decades of the nineteenth century, so-called banditti ruled several Illinois counties, in some cases locked in perpetual wars with citizen militias, vigilantes, or self-appointed “regulators,” who took it upon themselves to enforce the law. Property disputes over inadequately surveyed claims often ended in violence or lynchings, or both. The state’s most famous banditti were the Driscolls, a family of notorious horse thieves and murderers who terrorized Ogle County, north of Nauvoo, for most of 1841. The governor urged local citizens to bring the Driscoll gang to heel. However, the regulators’ first captain resigned when his grist mill was burned to the ground, and his horse tortured and killed. The Driscolls shot his successor after Sunday church services, in front of his wife and children. Finally, a posse of three hundred armed citizens showed up at the Driscolls’ farm and arrested the paterfamilias and two of his four outlaw sons. It was far from clear that the old man and the two sons had carried out the Sunday shooting, but the time had long passed for legal niceties. A quick, al fresco trial ensued. The county sheriff requested custody of the accused but was ignored.

One son, Pierce, walked free. Father John and his son William were condemned to hang. “We would rather be shot,” John Driscoll said. Honoring his request, the one-hundred-odd regulators present divided themselves into two massive firing squads. After shooting the father, who proclaimed his innocence, they showed William the body. “Would you like to confess now?” the mob asked. William admitted that he had murdered several men, albeit not the men he had been convicted of killing. He followed his father to the grave. The Driscolls “were fired upon by the whole company present, that there might be none who could be legal witnesses of the bloody deed,” wrote Thomas Ford, who noted that “these terrible measures put an end to the ascendancy of rogues in Ogle county.”

Eventually, the state tried a hundred men for the Driscoll murders. They were all acquitted, thanks to a clever maneuver by their defense attorney. The lawyer ensured that everyone present at the group execution was indicted for the murders. As defendants, they weren’t required to testify against themselves, and the only other eyewitnesses to the killings were dead. In his state history, Ford never mentioned that he was the complaisant judge who presided over the mass acquittal of the vigilantes.

UPON ARRIVING IN NAUVOO, THE MORMONS’ FIRST ORDER OF business was to seek a city charter from the state legislature. Partly, they wanted to protect themselves; the Saints sought to create a legally organized militia, to supplant the Danite guerilla force. To ensure the future of their nascent city-state, the Mormons wanted to legitimize their way of life in Illinois.

The result, approved by acclamation in 1840 by a legislature that included the young Lincoln (his future rival, the brash attorney Stephen Douglas, was already Illinois’s secretary of state), was the Nauvoo Charter, soon to become a controversial document. But it wasn’t controversial at the time. State senator Sidney Little, who represented neighboring McDonough County, duly noted the “extraordinary militia clause,” although he deemed it “harmless.” By the end of 1840, Nauvoo had about 2,400 new residents, and its own mini-constitution that enabled Joseph Smith to regulate Mormon life pretty much as he pleased.

The charter had three primary provisions. First, it created the Nauvoo Legion. Whereas most militias assembled their citizen soldiers from counties, or groups of counties, Nauvoo was the rare town to have its own fighting force. The charter explained that the Legion would operate independently of other militias, which reported to the governor as commander in chief. The Legion was a local police force, “at the disposal of the mayor in executing the laws and ordinances of the city corporation.” Joseph Smith was Nauvoo’s mayor from January 1842 until June 1844.

Second, the charter also created a University of Nauvoo, which never came into being. Like the notoriously over-officered Legion, however, the university did boast seventy-seven administrators, and again imitating the Legion, it reveled in ceremony. Although it never granted an actual degree, it did issue honorary degrees to two prominent newspaper editors—John Wentworth of the

Chicago Democrat

and James Gordon Bennett of the

New York Herald

—for printing favorable articles about the Saints. The repugnant Bennett, known as “His Satanic Majesty,” was perhaps the nation’s most powerful newspaper editor, and a Joseph Smith fan.

Chicago Democrat

and James Gordon Bennett of the

New York Herald

—for printing favorable articles about the Saints. The repugnant Bennett, known as “His Satanic Majesty,” was perhaps the nation’s most powerful newspaper editor, and a Joseph Smith fan.

But the charter’s third and most controversial provision was its distinctive court system, which effectively merged the executive and judicial branches of local government. As mayor, Joseph sat on the City Council and also served as chief justice of the municipal court. The associate justices were the City Council members and four aldermen. The mayor had “exclusive jurisdiction in all cases arising under the ordinances of the corporation” and reviewed all lower court decisions rendered by magistrates or justices of the peace. With very rare exceptions, all city councilmen, justices, and aldermen were Mormons. Because the charter required the Saints to obey the constitutions of both Illinois and the United States, litigants could theoretically appeal Nauvoo decisions to the state circuit court in Carthage, about twenty miles to the east. But the church frowned on appeals to Gentile justice, which they disdained as “lawing before the world.”

Joseph’s court arrogated to itself a broad power of habeas corpus, “in all cases arising under the ordinances of the City Council.” In its common law origins, habeas corpus (“surrender the body”) protected individuals from capricious imprisonment by state or local authorities. In Nauvoo, it was enforced indiscriminately to ensure that most Mormons could never be tried by an outside court. Although often used to protect Joseph from the many writs and summonses flying about him, the law likewise meant that a lapsed Saint charged with cattle thieving in neighboring Adams County could go free in Nauvoo, and generally did. After their Missouri experiences, the Saints craved safety above all, and sought legal, military, and political autarky to ensure that they alone could control their destiny in Illinois. The state granted them those rights; whether the Saints could preserve them would be another question entirely.

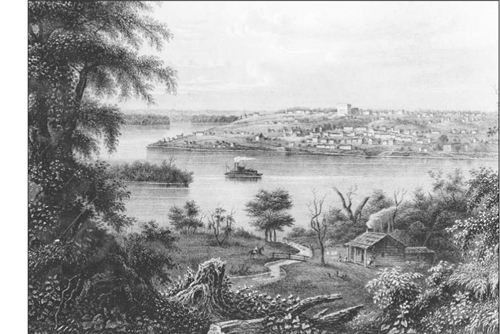

FROM 1839 TO 1842, NAUVOO’S POPULATION DOUBLED EACH YEAR. We were “growing like a mushroom (as it were, by magic),” bishop George Miller later wrote. By 1844, Nauvoo had swelled to over 10,000 residents. Although censuses were unreliable, some considered it to be the largest city in Illinois, bigger than the just-founded Chicago. Filling the peninsula created by the bend in the river, the town was laid out on a perpendicular grid. Each house lot was an acre, a half acre, or a quarter acre, with pockets of density on the south bank, near the first settlement, and on the cooler high ground near the temple site. House owners tended gardens and nursed orchards and farm animals in their backyards. In five years, the cluster of grim, weather-whipped log cabins had become a bona fide small city.

A bucolic view of Nauvoo, Illinois, as seen from the Mississippi River’s Iowa shoreline. The nearly competed Nauvoo Temple, lacking its steeple, is visible on the hill overlooking the town.

Credit: Utah State Historical Society

The town boasted two sawmills, a flour mill, a foundry, and a brewery. There was also a brick factory, a tannery, a bookbindery, a match factory, and innumerable craftsmen, for example, weavers, wagoners, cordwainers, and the like. By way of culture, Nauvoo had a zoo, a lyceum, three brass bands, and four taverns. (It was not until 1902 that alcohol consumption by observant Mormons was categorically forbidden.) Many residents, like Smith himself, had homes in the thickly settled town center and also owned farms outside the city.

Manufacturing never took hold in Nauvoo, to the Saints’ chagrin. But there was commerce aplenty. The Mississippi steamboat era was in full swing, and the church owned two paddle wheelers, often used to ferry arriving Saints upriver from New Orleans. There were four landing slips in Nauvoo, and in the summer as many as ten boats a week stopped by, often filled with tourists and day-trippers eager to catch a glimpse of the exotic Mormons. (“We are a curiosity, ain’t we?” Brigham Young once remarked.) But profitable trade eluded the Saints, who proved to be net importers of such everyday staples as wheat, corn, pork, sugar, coffee, tea, printed cloth, coal, and other household supplies. Prices were high, as high as in large Eastern cities like New York and Boston.

Nauvoo’s spiritual and geographic center of gravity was Joseph Smith himself. The town radiated outward from the tiny, riverside homestead he occupied in early 1839. Just across the street he built his two-story redbrick store, which was the Saints’ commercial and religious epicenter for many years. Joseph dispensed plots of land and even large cash loans from the store’s second-floor office, and for several years he ran a general store below. Under Joseph’s hand, the business quickly went bankrupt. He transferred ownership to more capable hands and tried to liquidate over $70,000 in debts using the new bankruptcy laws of 1842. As Brigham Young once joked about the Prophet’s lack of business acumen: “Joseph was a first-rate fellow with [his customers], provided he would never ask them to pay him.”

Joseph set to work on other building projects, including a (never-completed) tourist hotel, and a sacred temple on Nauvoo’s high ground. The temple would remain under construction during Joseph’s lifetime. Only the huge baptismal font in the basement, a twenty foot by twenty foot laver supported by twelve gigantic oxen—supposedly the same design as the “molten sea” in King Solomon’s temple in Jerusalem—was available to him for baptizing new Saints. Joseph first introduced followers to his new, secret temple rituals inside the store. He used canvas curtains to cordon off the second-floor meeting space into the rooms that would later become constituent parts of every Mormon temple in the world. Workmen painted a pastoral mural in the corner of one room and arranged cedar boughs, evergreens, and olive branches to resemble the Garden of Eden, the locus of Joseph’s endowment rite.

Like many of the uninitiated, church member Ebenezer Robinson was curious about the secret rituals administered upstairs in the store. But participants could not describe them, under penalty of death. A nonplussed Robinson once spotted Apostle John Taylor standing at the top of the stairway to the second floor, with a sword in hand, wearing a turban and a white robe. Robinson correctly surmised that Taylor was acting in the sacred endowment rite, representing “the cherubims and flaming sword which was placed at the east of the Garden of Eden, to guard the tree of life.”

Joseph also administered the new, secret rite of the Second Anointing for chosen couples upstairs at the store. He sealed polygamous marriages in the second-floor office, never revealing them to the Saints at large. Smith and Brigham Young kept coded records of these events, sometimes using pseudonyms. In his diary, Smith occasionally called himself “Baurak Ale.” To record his marriages, Young might write “saw E. Partridge,” a code which meant “[s]ealed [a]nd [w]ed Emily Partridge,” or “ME L. Beaman,” which would mean “married for eternity Louisa Beaman.” One of Joseph’s plural wives, Willard Richards’s sister Rhoda, lived in the store, which was also the site of Brigham Young’s soon-to-be-famous, botched seduction of British teenager Martha Brotherton.

Other books

Laura's Big Break by henderson, janet elizabeth

Surrendering To Her Sergeant by Angel Payne

Hidden Mercies by Serena B. Miller

The New Eve by Robert Lewis

The Strange Maid by Tessa Gratton

A Recipe for Bees by Gail Anderson-Dargatz

The Pope's Last Crusade by Peter Eisner

The Lost by Sarah Beth Durst

Beautyandthewolf by Carriekelly

An Unexpected Deity (Book 7) by Jeffrey Quyle