The Fry Chronicles (5 page)

Read The Fry Chronicles Online

Authors: Stephen Fry

I was a natural criminal because I lacked just that ability to resist temptation or to defer pleasure for one single second. Whatever guard there is on duty in the minds and moral make-ups of the majority had always been absent from his post in my mental barracks. I am thinking of the sentry who mans the barrier between excess and plenty, between right and wrong. ‘That’s enough Sugar Puffs for now, we don’t need another bowl,’ he would say in my friends’ heads or, ‘One chocolate bar would be ample.’ Or ‘Gosh, look, there’s some money. Tempting, but it isn’t ours.’ I never had such a guard on duty.

Actually that isn’t quite true. Where Pinocchio had Jiminy Cricket I had my Hungarian grandfather. He had died when I was ten, and ever since the day of his going I had been uncomfortably aware that he was looking down and grieving over what the Book of Common Prayer would call my manifold sins and wickedness. I had erred and strayed from my ways like a lost sheep, and there was no health in me. Grand-daddy watched me steal, lie and cheat; he caught me looking at illicit pictures in magazines and he saw me play with myself; he witnessed all my greed and lust and shame; but for all his heedful presence he could not prevent me from going to hell in my own way. If I had been psychopathic enough to feel no remorse or religious enough to believe in redemption through a divine outside agency, perhaps I should have been happier; as it was I had neither the consolation that I was free of guilt, nor the conviction that I could ever be forgiven.

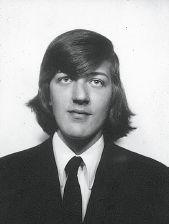

Grandpapa.

In gaol, everyone inside rolled their own cigarettes. A week’s wages could buy

nearly

enough Old Holborn or Golden Virginia tobacco to last the seven days until next payday. The cigarette papers, for no good reason that I could understand, were the usual Rizla+ brand, but presented in a buff-coloured pack with the words ‘H M Prisons Only’ printed at an angle across the flap. I hoarded as many of these as I could and contrived to smuggle them out on my release. For years afterwards I would refill these from the standard red, blue and green Rizla+ packs commercially available on the outside and enjoy the bragging rights of being seen with prison-issue rolling papers. Pathetic. I want so much to go back and slap myself sometimes. Not that I would pay the slightest attention.

As the prison week ended and the less careful inmates began to run out of burn they went through a peculiar begging ritual that I, never one to husband resources either, was quick to learn. You would spot someone smoking and slide ingratiatingly up to them. ‘Twos up, mate,’ you would wheedle and if you were the first to have got the request in you would be rewarded with their fag-end once they had done with it. These soggy second-hand butts,

whose few remaining strands of precious tobacco were all bitter and tarred by the smoke that had passed through them, were as a date palm in the desert, and I would smoke them right down until they burnt and blistered my lips. We all know the indignities to which enslaved humans will submit themselves in order to satisfy their addictions, whether for narcotics, alcohol, tobacco, sugar or sex. The desperation, savagery and degradation they publicly display make truffling pigs seem placid and composed by comparison. That image of myself scorching my mouth and fingertips as I hungrily hissed in a last hit of smoke should have been enough to tell me all I needed to know about myself. It wasn’t of course. I had decided at school, when it had been borne in on me how hopeless I was at sport, that I was a useful brain on top of a useless body. I was mind and spirit, while those around me were mud and blood. The truth that I was

more

a victim of physical need than they were I would angrily have repudiated. Which just goes to show how complete an arse I was.

Tragic hair. Tragic times. Taken some time between school and prison.

After a month or so of remand in Pucklechurch I was at last sentenced by the court to two years’ probation and released back to my parents. This time around I managed to enrol myself at a college and to sit for A levels and the Cambridge entrance paper.

†

Prison appeared to have marked the lowest point of my life. The suicide attempts,

†

tantrums and madness of my mid-teens seemed to be over. Back home in Norfolk I concentrated on academic work, achieved A grades and won a scholarship to read English at Queens’ College, Cambridge.

Now that I had the good news of my acceptance, I

faced the problem of what to do with the months leading up to the first term. Unlike today’s intrepid, elephant-hair-braceleted student adventurers and gap-year eco-warriors who hike the Inca trail, work with lepers in Bangladesh and dive and ski and surf and hang-glide and Facebook their way around the world having sex and wearing baggy shorts, I chose the already hideously old-fashioned challenge of teaching in a private school. I always believed that I was born to teach, and the world of the English prep school was one whose codes and manners I thoroughly understood. All the more reason for a stylish person to avoid such a place and seek new worlds and fresh challenges, one might suppose, but the systole and diastole of my disowning and belonging, rejecting and needing, escaping and returning was well established. I resist and scorn the England that bore me with the same degree of intensity with which I embrace and revere it. Perhaps too I felt that I owed it to myself to put right the failures of my own schooling by helping with the schooling of others. There was also the example of two of my literary heroes, Evelyn Waugh and W. H. Auden, who had each trodden this path. Waugh had even got material for his first novel out of the experience. Perhaps I would too.

I had added my name to the roll of would-be schoolmasters, a roll that resided somewhere in a copperplate hand amongst the roll-top desks, deckled ledgers and Eastlight boxfiles in the cosy, womblike offices of the scholastic agency Gabbitas-Thring, in Sackville Street, Piccadilly. Just two days after registering, a thin, piping voice called me up in Norfolk.

‘We have a vacancy at a very nice prepper in North Yorkshire. Cundall Manor. Latin, Greek, French and a

little light rugger and soccer refereeing. As well as the usual duties, of course. Does that appeal?’

‘Gosh. That’s great. Do I have to go up for an interview?’

‘Well now, the happy fact is that Mr Valentine, the father of Cundall’s headmaster Jeremy Valentine, lives not far from you in Norfolk. He will see you.’

Mr Valentine was kind and cardiganned and very interested in my views on cricket. He poured me a generous schooner of amontillado and conceded that, while this young Botham chap could certainly swing the ball, his line and length were surely too erratic to trouble any technically correct batsman. Of Latin and Greek there was no discussion. Nor, thankfully, of rugger or soccer. I was commended on my choice of college.

‘Queens’ used to have a pretty decent Cuppers side in my day. Oliver Popplewell kept wicket. First class.’

I forbore to mention that this same Oliver Popplewell, a friend of the family and now a distinguished QC, had just a few months earlier stood up in his wig and gown and spoken on my behalf at a criminal hearing in Swindon.

†

It didn’t seem like the right moment.

Valentine Senior stood up and shook my hand.

‘I expect they’ll want you as soon as possible,’ he said. ‘You can catch the fast train to York at Peterborough.’

‘So I’ve … you’re …’

‘Heavens yes. Just the sort of chap Jeremy will be delighted to have on the staff.’

I caught the train and arrived at Cundall a teacher and ‘just the sort of chap’.

Was I now so very different a figure from the thieving, deceitful little shit who had been such a torment to his

family for the past ten years? Was all the fury, dishonesty and desire gone? All passion spent, all greed sated? I certainly didn’t believe that I was likely to steal again. I had grown up enough to know how to focus and work and take responsibility for myself. All the adult voices that had shouted in my ear (Think, Stephen. Use your common sense. Work. Concentrate. Consider other people. Think. Think, think,

think!

) seemed finally to have got through. I had an honest, ordered, respectable and unexciting life to look forward to. I had sown my wild oats and it was time to grow sage.

Or so I imagined.

I was still a smoker. In fact, to suit my new role of schoolmaster I had moved from hand-rolled cigarettes to a pipe. My father had smoked pipes throughout my childhood. Sherlock Holmes, veneration of whom had been the direct cause of my expulsion from Uppingham,

†

was the most celebrated pipe smoker of them all. A pipe was to me a symbol of work, thought, reason, self-control, concentration (‘It is quite a three pipe problem, Watson’), maturity, insight, intellectual strength, manliness and moral integrity. My father and Holmes had all those qualities, and I wanted to reassure myself and those around me that I did too. Another reason for choosing a pipe, I suppose, was that at Cundall Manor, the Yorkshire prep school at which I had been offered a post as an assistant master, I was closer in age to the boys than to the other members of staff and I felt therefore that I required a look that would mark me out as an adult; a briar pipe and a tweed jacket with leather patches at the elbows seemed to answer the case perfectly. The fact that a lanky late-adolescent smoking a pipe looks the worst kind of

pompous and pretentious twazzock did not cross my mind, and those around me were too kind to point it out. The boys called me the Towering Inferno, but, perhaps because the headmaster was also a pipe smoker, the habit itself went unchallenged.

I still had no need to shave, and the flop of straight hair that to this day I can do nothing about continued to contradict my desire to project maturity. Looking more pantywaist than professorial and more milquetoast than macho, I puffed benignly about the school as happy as I had ever been in all my young life.

Having said which, the first week had been hell. It had never occurred to me that teaching could be so tiring. My duties, as a valet would say, were extensive: not just teaching and keeping order in the form-room but preparing lessons, correcting and marking written work, giving extra tuition, covering for other masters and being on call for everything and everyone from the morning bell before breakfast to lights-out at night. Since I lived in the school and had no ties of marriage outside it, the headmaster and other senior staff were able to make as much use of me as they wished. I had ostensibly been hired as the replacement for a sweet, gentle old fellow called Noel Kemp-Welch, who had slipped on the ice and fractured his pelvic girdle at the beginning of term. The kernel of my work therefore was to take his Latin, Greek and French lessons, but I very soon found myself standing in for the headmaster and other members of staff giving classes in history, maths, geography and science. On my third day I was told to go and teach biology to the Upper Fifth.