Patricide (14 page)

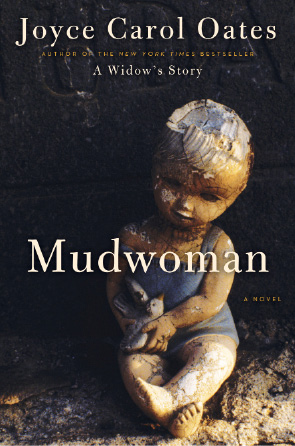

Authors: Joyce Carol Oates

Â

Please enjoy this excerpt from Joyce Carol Oates's novel

Mudwoman

,

available now from Ecco

Mudgirl is a child abandoned by her mother in the silty flats of the Black Snake River. Cast aside, Mudgirl survives by an accident of fateâor destiny. After her rescue, the well-meaning couple who adopt Mudgirl quarantine her poisonous history behind the barrier of their middle-class values, seemingly sealing it off forever. But the bulwark of the present proves surprisingly vulnerable to the agents of the past.

Meredith “M.R.” Neukirchen is the first woman president of an Ivy League university. Her commitment to her career and moral fervor for her role are all-consuming. Involved with a secret lover whose feelings for her are teasingly undefined, and concerned with the intensifying crisis of the American political climate as the United States edges toward war with Iraq, M.R. is confronted with challenges to her leadership which test her in ways she could not have anticipated. The fierce idealism and intelligence that delivered her from a more conventional life in her upstate New York hometown now threaten to undo her.

A reckless trip upstate thrusts M.R. Neukirchen into an unexpected psychic collision with Mudgirl and the life M.R. believes she has left behind. A powerful exploration of the enduring claims of the past,

Mudwoman

is at once a psychic ghost story and an intimate portrait of a woman cracking the glass ceiling at enormous personal cost, which explores the tension between childhood and adulthood, the real and the imagined, and the “public” and “private” in the life of a highly complex contemporary woman.

Â

I

n fact there had been inhabitants along the Mill Run Road, and not too long agoâan abandoned house, set back in a field like a gaunt and etiolated elder; a Sunoco station amid a junked-car lot, that appeared to be closed; and an adjoining café where a faded sign rattled in the windâ

BLACK

RIVER

CAFÃ.

Both the Sunoco station and the café were boarded up. Just outside the café was a pickup truck shorn of wheels. M.R. might have turned into the parking lot here butâso strangelyâfound herself continuing forward as if drawn by an irresistible momentum.

She was smilingâwas she? Her brain, ordinarily so active, hyperactive as a hive of shaken hornets, was struck blank in anticipation.

In hilly countryside, foothills and densely wooded mountains, you can see the sky only in patchesâM.R. had glimpses of a vague blurred blue and twists of cloud like soiled bandages. She was driving in odd rushes and jolts pressing her foot on the gas pedal and releasing itâshe was hoping not to be surprised by whatever lay ahead and yet, she was surprisedâshocked: “Oh God!”

For there was a child lying at the side of the roadâa small figure lying at the side of the road broken, discarded. The Toyota veered, plunged off the road into a ditch.

Unthinking M.R. turned the wheel to avoid the child. There came a sickening thud, the jolt of the vehicle at a sharp angle in the ditchâthe front left wheel and the rear left wheel.

So quickly it had happened! M.R.'s heart lurched in her chest. She fumbled to open the door, and to extract herself from the seat belt. The car engine was still onâa violent peeping had begun. She'd thought it had been a child at the roadside but of courseâshe saw nowâit was a doll.

Mill Run Road. Once, there must have been a mill of some sort in this vicinity. Now, all was wilderness. Or had reverted to wilderness. The road was a sort of open landfill used for dumpingâin the ditch was a mangled and filthy mattress, a refrigerator with a door agape like a mouth, broken plastic toys, a man's boot.

Grunting with effort M.R. managed to climbâto crawlâout of the Toyota. Then she had to lean back inside, to turn off the ignitionâa wild thought came to her, the car might explode. Her fingers fumbled the keysâthe keys fell onto the car floor.

She sawâit wasn't a doll either at the roadside, only just a child's clothing stiff with filth. A faded-pink sweater and on its front tiny embroidered roses.

And a child's sneaker. So small!

Tangled with the child's sweater was something white, cottonâunderpants?âstiff with mud, stained. And socks, white cotton socks.

And in the underbrush nearby the remains of a kitchen table with a simulated-maple Formica top. Rural America, filling up with trash.

An entire household dumped out on the Mill Run Road! Not a happy story.

M.R. stooped to inspect the refrigerator. Of course it was emptyâthe shelves were rusted, badly battered. There was a smell. A sensation of such uneaseâoppressionâcame over her, she had to turn away.

[ . . . ]

This side of the Black Snake River were stretches of marshland, mudflats. She'd been smelling mud. You could see that the river often overran its banks here. There was a harsh brackish smell as of rancid water and rotted things.

Amid the mudflats was a sort of peninsula, a spit of land raised about three feet, very likely man-made, like a dam; M.R. climbed up onto it. She was a strong woman, her legs and thighs were hard with muscle beneath the soft, just slightly flabby female flesh; she made an effort to swim, hike, run, walkâshe “worked out” in the University gym; still, she quickly became breathless, panting. For there was something very oppressive about this placeâthe acres of mudflats, the smell.

Even on raised ground she was walking in mudâher nice shoes, mudsplattered.

Her feet were wet.

She thought

I

must

turn

back.

As

soon

as

I

can.

She thought

I

will

know

what

to

doâthis

can

be

made

right.

Staring at her watch trying to calculate but her mind wasn't working with its usual efficiency. And her eyesâwas something wrong with her eyes?

[ . . . ]

Stress, overwork the doctor had told her. Hours at the computer and when she glanced up her vision was distorted and she had to blink, squint to bring the world into some sort of focus.

How faraway that worldâthere could be no direct route to that world, from the Mill Run Road.

A

crouched

figure.

Bearded

face,

astonished

eyes.

Slung

over

his

shoulder

a

half-dozen

animal

traps.

With

a

gloved

hand

prodding

atâwhatever

it

was

in

the

mud.

“Hello? Is someone . . . ?”

She was making her way along the edge of a makeshift dam. It was a dam comprised of boulders and rocks and it had acquired over the years a sort of mortar of broken and rotted tree limbs and even animal carcasses and skeletons. Everywhere the mudflats stretched, everywhere cattails and rushes grew in profusion. There were trees choked with vines. Dead trees, hollow tree-trunks. The pond was covered in algae bright-green as neon that looked as if it were quivering with microscopic life and where the water was clear the pebble-sky was reflected like darting eyes. She was staring at the farther shore where she'd seen something moveâshe thought she'd seen something move. A flurry of dragonflies, flash of birds' wings. Bursts of autumn foliage like strokes of paint and deciduous trees looking flat as cutouts. She waited and saw nothing. And in the mudflats stretching on all sides nothing except cattails, rushes stirred by the wind.

She was thinking of something her (secret) lover had once saidâ

There

is

no

truth

except

perspective.

There

are

no

truths

except

relations.

She had seemed to know what he'd meant at the timeâhe'd meant something matter-of-fact yet intimate, even sexual; she was quick to agree with whatever her lover said in the hope that someday, sometime she would see how self-evident it was and how crucial for her to have agreed at the time.

Thinking

There

is

a

position,

a

perspective

here.

This

spit

of

land

upon

which

I

can

walk,

stand;

from

which

I

can

see

that

I

am

already

returned

to

my

other

life,

I

have

not

been

harmed

and

will

have

begun

to

forget.

Thinking

This

is

all

past,

in

some

future

time.

I

will

look

back,

I

will

have

walked

right

out

of

it.

I

will

have

begun

to

forget.

[ . . . ]

At the end of the peninsula there wasânothing. Mudflats, desiccated trees. In the Adirondacks, acid rain had been falling for yearsâparts of the vast forest were dying.

“Hello?”

Strange to be calling out when clearly no one was there to hear. M.R.'s uplifted hand in a ghost-greeting.

He'd been a trapperâthe bearded man. Hauling cruel-jawed iron traps over his shoulder. Muskrats, rabbits. Squirrels. His prey was small furry creatures. Hideous deaths in the iron traps, you did not want to think about it.

Hey!

Little

girlâ?

She turned back. Nothing lay ahead.

Retracing her steps. Her footprints in the mud. Like a drunken person, unsteady on her feet. She was feeling oddly excited. Despite her tiredness, excited.

She returned to the littered roadwayâthere, the child's clothing she'd mistaken so foolishly for a doll, or a child. There, the Toyota at its sharp tilt in the ditch. Within minutes a tow truck could haul it out, if she could contact a garageâso far as she could see the vehicle hadn't been seriously damaged.

[ . . . ]

She walked on, not certain where she was headed. The sky was darkening to dusk. Shadows lifted from the earth. She saw lights aheadâlights?âthe gas station, the caféâto her surprise and relief, these appeared to be open.

[ . . . ]

M.R. couldn't believe her good luck! She would have liked to cry with sheer relief. Yet a part of her brain thinking calmly

Of

course.

This

has

happened

before.

You

will

know

what

to

do.

At a gas pump stood an attendant in soiled bib overalls, shirtless, watching her approach. He was a fattish man with snarled hair, a sly fox-face, watching her approach. Uneasily M.R. wonderedâwould the attendant speak to her, or would she speak to him, first? She was trying not to limp. Her leather shoes were hurting her feet. She didn't want a stranger's sympathy, still less a stranger's curiosity.

“Ma'am! Somethin' happen to ya car?”

There was a smirking sort of sympathy here. M.R. felt her face heat with blood.

She explained that her car had broken down about a mile away. That isâher car was partway in a ditch. Apologetically she said: “I could almost get it out by myselfâthe ditch isn't deep. But . . .”

How pathetic this sounded! No wonder the attendant stared at her rudely.

“Ma'amâyou look familiar. You're from around here?”

“No. I'm not.”

“Yes, I know you, ma'am. Your face.”

M.R. laughed, annoyed. “I don't think so. No.”

Now came the sly fox-smile. “You're from right around here, ma'am, eh? Hey sureâI know you.”

“What do you mean? You knowâme? My name?”