Jonathan Strange and Mr Norrell (21 page)

Read Jonathan Strange and Mr Norrell Online

Authors: Susanna Clarke

Tags: #Fiction, #Fantasy, #Historical, #Literary, #Media Tie-In, #General

There is not much to interest the serious student of magic in the early issues and the only entertainment to be got from them is contained in several articles in which Portishead attacks on Mr Norrell's behalf: gentleman-magicians; lady-magicians; street-magicians; vagabond-magicians; child-prodigy-magicians; the Learned Society of York Magicians; the Learned Society of Manchester Magicians; learned societies of magicians in general; any other magicians whatsoever.

1 Four years later during the Peninsular War Mr Norrell's pupil, Jonathan Strange, had similar criticisms to make about this form of magic.

2 In this speech Mr Lascelles has managed to combine all Lord Portishead's books into one. By the time Lord Portishead gave up the study of magic in early 1808 he had published three books:

The Life of Jacques Belasis

, pub. ongman, London, 1801,

The Life of Nicholas Goubert

, pub. Longman, London, 1805, and

A Child's History of the Raven King

, pub. Longman, London, 1807, engravings by Thomas Bewick. The first two were scholarly discussions of two sixteenth-century magicians. Mr Norrell had no great opinion of them, but he had a particular dislike of

A Child's History

. Jonathan Strange, on the other hand, thought this an excellent little book.

3 “It was odd that so wealthy a man — for Lord Portishead counted large portions of England among his possessions — should have been so very self-effacing, but such was the case. He was besides a devoted husband and the father of ten children. Mr Strange told me that to see Lord Portishead play with his children was the most delightful thing in the world. And indeed he was a little like a child himself. For all his great learning he could no more recognize evil than he could spontaneously understand Chinese. He was the gentlest lord in all of the British aristocracy.”

The Life of Jonathan Strange

by John Segundus, pub. John Murray, London, 1820.

4

The Friends of English Magic

was first published in February 1808 and was an immediate success. By 1812 Norrell and Lascelles were boasting of a circulation in excess of 13,000, though how reliable this figure may be is uncertain.

From 1808 until 1810 the editor was nominally Lord Portishead but there is little doubt that both Mr Norrell and Lascelles interfered a great deal. There was a certain amount of disagreement between Norrell and Lascelles as to the general aims of the periodical. Mr Norrell wished

The Friends of English Magic

first to impress upon the British Public the great importance of English modern magic, secondly to correct erroneous views of magical history and thirdly to vilify those magicians and classes of magicians whom he hated. He did not desire to explain the procedures of English magic within its pages — in other words he had no intention of making it in the least informative. Lord Portishead, whose admiration of Mr Norrell knew no bounds, considered it his first duty as editor to follow Norrell's numerous instructions. As a result the early issues of

The Friends of English Magic

are rather dull and often puzzling — full of odd omissions, contradictions and evasions. Lascelles, on the other hand, understood very well how the periodical might be used to gain support for the revival of English magic and he was anxious to make it lighter in tone. He grew more and more irritated at Portishead's cautious approach. He manoeuvred and from 1810 he and Lord Portishead were joint editors.

John Murray was the publisher of

The Friends of English Magic

until early 1815 when he and Norrell quarrelled. Deprived of Norrell's support, Murray was obliged to sell the periodical to Thomas Norton Longman, another publisher. In 1816 Murray and Strange planned to set up a rival periodical to

The Friends of English Magic

, entitled

The Famulus

, but only one issue was ever published.

13

The magician of Threadneedle-street

December 1807

T

HE MOST FAMOUS street-magician in London was undoubtedly Vinculus. His magician's booth stood before the church of St Christopher Le Stocks in Threadneedle-street opposite the Bank of England, and it would have been difficult to say whether the bank or the booth were the more famous.

Yet the reason for Vinculus's celebrity — or notoriety — was a little mysterious. He was no better a magician than any of the other charlatans with lank hair and a dirty yellow curtain. His spells did not work, his prophecies did not come true and his trances had been proven false beyond a doubt.

For many years he was much addicted to holding deep and weighty conference with the Spirit of the River Thames. He would fall into a trance and ask the Spirit questions and the voice of the Spirit would issue forth from his mouth in accents deep, watery and windy. On a winter's day in 1805 a woman paid him a shilling to ask the Spirit to tell her where she might find her runaway husband. The Spirit provided a great deal of quite surprizing information and a crowd began to gather around the booth to listen to it. Some of the bystanders believed in Vinculus's ability and were duly impressed by the Spirit's oration, but others began to taunt the magician and his client. One such jeerer (a most ingenious fellow) actually managed to set Vinculus's shoes on fire while Vinculus was speaking. Vinculus came out of his trance immediately: he leapt about, howling and attempting to pull off his shoes and stamp out the fire at one and the same time. He was throwing himself about and the crowd were all enjoying the sight immensely, when something popt out of his mouth. Two men picked it up and examined it: it was a little metal contraption not more than an inch and a half long. It was something like a mouth-organ and when one of the men placed it in his own mouth he too was able to produce the voice of the Spirit of the River Thames.

Despite such public humiliations Vinculus retained a certain authority, a certain native dignity which meant that he, among all the street-magicians of London, was treated with a measure of respect. Mr Norrell's friends and admirers were continually urging him to pay a visit to Vinculus and were surprized that he shewed no inclination to do it.

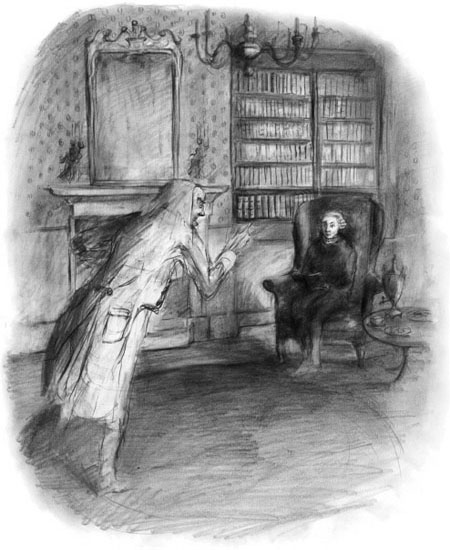

On a day in late December when storm clouds made Alpine landscapes in the sky above London, when the wind played such havoc in the heavens that the city was one moment plunged in gloom and the next illuminated by sunlight, when rain rattled upon the windowpane, Mr Norrell was seated comfortably in his library before a cheerful fire. The tea table spread with a quantity of good things stood before him and in his hand was Thomas Lanchester's

The Language of Birds

. He was turning the pages in search of a favourite passage when he was nearly frightened out of his wits by a voice suddenly saying very loudly and contemptuously, “Magician! You think that you have amazed everyone by your deeds!”

Mr Norrell looked up and was astonished to find that there was someone else in the room, a person he had never seen before, a thin, shabby, ragged hawk of a man. His face was the colour of three-day-old milk; his hair was the colour of a coal-smoke-and-ashes London sky; and his clothes were the colour of the Thames at dirty Wapping. Nothing about him — face, hair, clothes — was particularly clean, but in all other points he corresponded to the common notion of what a magician should look like (which Mr Norrell most certainly did not). He stood very erect and the expression of his fierce grey eyes was naturally imperious.

“Oh, yes!” continued this person, glaring furiously at Mr Norrell. “You think yourself a very fine fellow! Well, know this, Magician! Your coming was foretold long ago. I have been expecting you these past twenty years! Where have you been hiding yourself?”

Mr Norrell sat in amazed silence, staring at his accuser with open mouth. It was as if this man had reached into his breast, plucked out his secret thought and held it up to the light. Ever since his arrival in the capital Mr Norrell had realized that he had indeed been ready long ago; he could have been doing magic for England's benefit years before; the French might have been defeated and English magic raised to that lofty position in the Nation's regard which Mr Norrell believed it ought to occupy. He was tormented with the idea that he had betrayed English magic by his dilatoriness. Now it was as if his own conscience had taken concrete form and started to reproach him. This put him some-what at a disadvantage in dealing with the mysterious stranger. He stammered out an inquiry as to who the person might be.

“I am Vinculus, magician of Threadneedle-street!”

“Oh!” cried Mr Norrell, relieved to find that at least he was no supernatural apparition. “And you have come here to beg I suppose? Well, you may take yourself off again! I do not recognize you as a brother-magician and I shall not give you any thing! Not money. Not promises of help. Not recommendations to other people. Indeed I may tell you that I intend . . .”

“Wrong again, Magician! I want nothing for myself. I have come to explain your destiny to you, as I was born to do.”

“Destiny? Oh, it's prophecies, is it?” cried Mr Norrell contemptuously. He rose from his chair and tugged violently at the bell pull, but no servant appeared. “Well, now I really have nothing to say to people who pretend to do prophecies.

Lucas!

Prophecies are without a doubt one of the most villainous tricks which rascals like you play upon honest men. Magic cannot see into the future and magicians who claimed otherwise were liars.

Lucas!

”

Vinculus looked round. “I hear you have all the books that were ever written upon magic,” he said, “and it is commonly reported that you have even got back the ones that were lost when the library of Alexandria burnt — and know them all by heart, I dare say!”

“Books and papers are the basis of good scholarship and sound knowledge,” declared Mr Norrell primly. “Magic is to be put on the same footing as the other disciplines.”

Vinculus leaned suddenly forward and bent over Mr Norrell with a look of the most intense, burning concentration. Without quite meaning to, Mr Norrell fell silent and he leaned towards Vinculus to hear whatever Vinculus was about to confide to him.

“

I reached out my hand

,” whispered Vinculus, “

England's rivers turned and flowed the other way

. . .”

“I beg your pardon?”

“

I reached out my hand

,” said Vinculus, a little louder, “

my enemies's blood stopt in their veins

. . .” He straightened himself, opened wide his arms and closed his eyes as if in a religious ecstasy of some sort. In a strong, clear voice full of passion he continued:

“

I reached out my hand; thought and memory flew out of my enemies' heads like a flock of starlings;

My enemies crumpled like empty sacks.

I came to them out of mists and rain;

I came to them in dreams at midnight;

I came to them in a flock of ravens that filled a northern sky at dawn;

When they thought themselves safe I came to them in a cry that broke the silence of a winter wood . . .

”

“Yes, yes!” interrupted Mr Norrell. “Do you really suppose that this sort of nonsense is new to me? Every madman on every street-corner screams out the same threadbare gibberish and every vagabond with a yellow curtain tries to make himself mysterious by reciting something of the sort. It is in every third-rate book on magic published in the last two hundred years! `I came to them in flock of ravens!' What does that

mean

, I should like to know? Who ame to whom in a flock of ravens?

Lucas!

”

Vinculus ignored him. His strong voice overpowered Mr Norrell's weak, shrill one.

“

The rain made a door for me and I went through it;

The stones made a throne for me and I sat upon it;

Three kingdoms were given to me to be mine forever;

England was given to me to be mine forever.

The nameless slave wore a silver crown;

The nameless slave was a king in a strange country

. . .”

“Three kingdoms!” exclaimed Mr Norrell. “Ha! Now I understand what this nonsense pretends to be! A prophecy of the Raven King! Well, I amsorry to tell you that if you hope to impress me by recounting tales of that gentleman you will be disappointed. Oh, yes, you are entirely mistaken! There is no magician whom I detest more!”

1