Fordlandia (38 page)

Authors: Greg Grandin

Tags: #Industries, #Brazil, #Corporate & Business History, #Political Science, #Fordlândia (Brazil), #Automobile Industry, #Business, #Ford, #Rubber plantations - Brazil - Fordlandia - History - 20th century, #History, #Fordlandia, #Fordlandia (Brazil) - History, #United States, #Rubber plantations, #Planned communities - Brazil - History - 20th century, #Business & Economics, #Latin America, #Planned communities, #Brazil - Civilization - American influences - History - 20th century, #20th Century, #General, #South America, #Biography & Autobiography, #Henry - Political and social views

Driving home from the trial, which he won, though the six-cent settlement he received was more a rebuke than a vindication, Ford turned to his secretary, Ernest Liebold, and said, “I’m going to start up a museum and give people a true picture of the development of the country.” He also soon decided to build a town to go with the museum, asking without any prior conversation Edward Cutler, an architect in his employ, to draw him plans for a village. It was, said Cutler, “purely imaginative.”

Over the next decade, Ford became the most famous antique collector in the world. Crates arrived daily in Dearborn, filling up the bays and warehouse of Building 13 of his now vacant tractor plant (production had been moved to the Rouge). Trucks and Michigan Central boxcars delivered anything one could imagine related to the mechanical or decorative arts—cast-iron stoves, sewing machines, threshers, plows, baby bottles, scrubbing boards, saucepans, vacuum cleaners, inkwells, steam engines, oil lamps, typewriters, mirrors, barber chairs, hobby horses, fire engines, kitchen utensils, Civil War drums, trundle beds, rocking chairs, benches, tables, spinning wheels, music boxes, violins, clocks, lanterns, kettles, cradles, candle molds, airplanes, trains, and cars. “We are trying,” Ford told a

New York Times

reporter, “to assemble a complete series of every kind of article used or made in America from the days of the first settlers down to now. When we are through we shall have reproduced American life as lived.”

14

In October 1927—just a few days after Pará’s legislature ratified Ford’s Tapajós concession—Ford began work on both his town and his museum, modeled on Philadelphia’s Independence Hall, to house and display his collection. Bulldozers cleared a two-hundred-acre lot and leveled off a knoll overlooking the Rouge River and workers started to lay the foundation for the Martha-Mary Chapel—built with bricks from the church where Clara and Henry were married and named after their respective mothers. Just upstream lay Ford’s Fair Lane estate, a few miles downriver stood the Rouge factory, and the new town was built almost in the shadow of the smokestack crown of the complex’s Powerhouse No. 1—eight chimneys as harmonious in their proportions as the eight columns holding up each of the Parthenon’s two façades. “Life flows,” Ford liked to repeat, but he would have a say in its course. Just as Blakeley and Villares were felling the first trees at Boa Vista, surveyors squared the site of a village green and workers began to lay railroad tracks and reassemble the scores of buildings that had been shipped from all over America—an 1803 Connecticut post office, the Wright brothers’ bicycle shop, Abraham Lincoln’s Illinois courtroom, Luther Burbank’s botanical lab from California, Edgar Allan Poe’s New York cottage, the homes of Patrick Henry, Daniel Webster, and Walt Whitman, Ford’s childhood family farm, the Detroit shed where he built his first gas-powered “quadricycle,” and, of course, Thomas Edison’s Menlo Park, New Jersey, laboratories.

15

Ford named the settlement Greenfield Village, after his wife’s childhood county, which by then had been absorbed by Detroit’s sprawl.

Ford demanded historical faithfulness, ordering his engineers to rescue as much original detail from the structures and their surroundings as possible. For Edison’s Menlo Park complex, he had seven boxcar loads of red clay shipped from New Jersey, along with the stump of an old hickory tree that was on the grounds. “H’m!” said Edison upon seeing the restoration, “the same damn old New Jersey clay!” Greenfield Village had everything that one could imagine as defining an American town before the arrival of Fordist mass production—a town hall, schools, a fire station, a doctor’s office, a blacksmith, covered bridges, clapboard residences with neat flower gardens, and even liquor bottles (filled with colored water) in the inn’s taverns, which Ford the teetotaler only grudgingly allowed after being urged by his wife. There was one detail, though, one mainstay of nineteenth-century small-town America, that Ford refused to replicate: a bank. The Ford Motor Company may have been forced to go into the lending business by setting up its Universal Credit Corporation, but Ford’s vision of Americana would remain pure. His Main Street would stay forever untainted by Wall Street.

16

Many in the press judged Ford’s antiquarianism with contempt, pointing out the irony of the man singularly responsible for the disappearance of small-town America now claiming to be its restorer. “With his left hand he restores a self-sufficient little eighteenth-century village,” wrote the

Nation

, “but with his right hand he had already caused the land to be dotted red and yellow with filling stations.” “It was,” said the

New York Times

, “as if Stalin went in for collecting old ledgers and stock-tickers.” The

New Republic

chimed in: “Mr. Ford might be less interested in putting an extinct civilization into a museum if he had not done so much to make it extinct.” And many intellectuals were particularly disapproving of his museum. Ford refused to consult curators to guide his collecting (even as in the Amazon he was forswearing botanists to help with his rubber plantation). One assistant remembers that Ford was “afraid of bringing in experts whose opinions might run counter to his.” When his museum finally opened, it looked like, as one historian put it, “the world’s biggest rummage sale,” organized with no rhyme or reason.

17

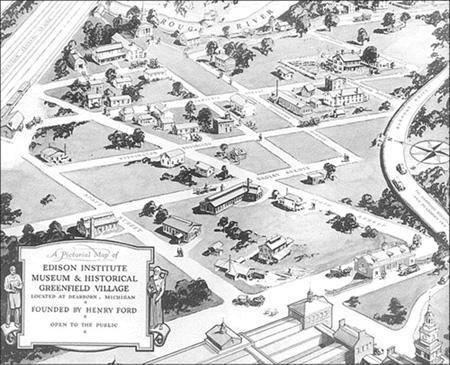

When an interviewer asked Edward Cutler, the architect of Greenfield Village, rendered above in a 1934 tourist map, if it was true that “just out of the clear sky one day, Ford asked you to draw a village,” Cutler replied “yes.”

There was, however, logic at work. The vision of technological progress on display in Ford’s museum and village—from the crafts era through mechanical steam engines to industrial manufacturing—was obviously self-serving, ending in the revolution in mass production that he presided over. Yet there is also a deep weariness revealed in this vision, a distrust of the flash of consumerism that had overtaken the American economy, driven by dotted-line loans and the induced demand of “trumpery and trinkets,” as Ford put it, goods which performed “no real service to the world and are at last mere rubbish as they were at first mere waste.” Conceived during the roiling twenties when his company was forced to adopt yearly model changes and easy loans, Greenfield Village and its museum, along with Ford’s obsessive, massive collecting of material goods and historical buildings, was an antidote to the fetishism of cheap consumer products that had overtaken the economy, and the hucksterism that sold them. The stock market crash and the onset of an intractable depression, followed by the aftershocks of successive banking crises, only heightened Ford’s desire for solidity. The items in his village and museum embodied the social relations and knowledge that went into making them, preserving the essence, in fact the breath—when it opened, his museum displayed Thomas Edison’s last exhalation, captured by his son in a test tube at Ford’s request—of a more durable American experience. “We learn from the past not only what to do but what not to do,” Ford once told an interviewer. “Whatever is produced today has something in it of everything that has gone before. Even a present-day chair embodies all previous chairs, and if we can show the development of the chair in tangible form we shall teach better than we can in books.” He said that one shouldn’t “regard these thousands of inventions, thousands of things which man has made, as just so many material objects. You can read in every one of them what the man who made them was thinking—what he was aiming at. A piece of machinery or anything that is made is like a book, if you can read it. It is part of the record of man’s spirit.”

18

DIEGO RIVERA DIDN’T share the scorn other intellectuals and artists heaped on Greenfield Village. During his stay in Detroit, Rivera visited the model town, wandering around its streets, houses, mills, and workshops from seven in the morning to one thirty the next. He recognized its sense of proportion and how it related to the nearby River Rouge plant. “As I walked on, marveling at each successive mechanical wonder,” he recalled in his memoirs, “I realized that I was witnessing the history of machinery, as if on parade, from its primitive beginnings to the present day, in all its complex and astounding elaboration.”

19

The holism that Rivera identified in Ford represents a particular kind of pastoralism, an American pastoralism that didn’t oppose nature and industrialization, or man and the machine, but saw each fulfilling the other. Much of Ford’s faith that industry and agriculture could be balanced and that community would be fulfilled rather than overrun by capitalist expansion drew specifically from Ralph Waldo Emerson. Yet it’s a conviction that had deep roots in American thought. As historian Leo Marx has pointed out, with the exception of the Southern slave states, American history reveals little opposition to mechanization and industrialization. America itself, Marx wrote, has often been held up by many of its celebrants as a machine in the New World garden, representing both a release of historical energy through the “seizure of the underlying principles of nature” and a domestication of that power through its Constitution—described as a “machine that would go of itself,” a self-regulating, synchronized system of checks and balances.

20

The main struts of Henry Ford’s philosophy all had antecedents in eighteenth- and nineteenth-century American political and literary concepts: that mechanization marked not the conquest but the realization of nature’s secrets and thus the attainment of the pastoral ideal; that history is best understood as the progress of this realization, of the gradual liberation of humans from soul-crushing toil; and that America has a providential role to play in world history in achieving this liberation. It was from such wellsprings of technological optimism that Ford was drawing when he predicted that his Muscle Shoals project would “make a new Eden of our Mississippi Valley, turning it into the great garden and powerhouse of the country.” Against Marxists who warned that an impending “crisis of overproduction” would bring down capitalism, Ford countered by predicting that “the day of actual overproduction is the day of emancipation from enslaving materialistic anxiety.” To those who thought industrialization deadened mind and spirit, Ford responded by saying that want was the true cause of alienation. “The unfortunate man whose mind is continually bent to the problem of his next meal or the next night’s shelter is a materialist perforce,” he said. “Now, emancipate this man by economic security and the appurtenances of social decency and comfort, and instead of making him more of a materialist you liberate him.”

21

These and similar pronouncements were not merely self-aggrandizing conceits on Ford’s part. Many saw the cheap, durable car he made available to the multitudes as the “spontaneous fruit of an Edenic tree,” to quote the Spanish philosopher José Ortega y Gasset’s description of the quickness with which man embraced the automobile. What else could explain the effortlessness with which the Model T, after its demise, could be transformed into an object of pastoral nostalgia, as ornery as the animal it replaced? “If the emergency brake hadn’t been pulled all the way back,” E. B. White wrote in a 1936

New Yorker

essay titled “Farewell, My Lovely,” “the car advanced on you the instant the first explosion occurred and you would hold it back by leaning your weight against it. I can still feel my old Ford nuzzling me at the curb, as though looking for an apple in my pocket.”

22

As a response to the Great Depression, Ford’s drive for balance and holistic self-sufficiency manifested itself in a number of ways: he increased his commitment to village industries and hydroelectricity; he said small household gardens would do more to offset poverty than government relief and urged his River Rouge workers to grow their own food; and he promoted his “Industrialized American Barn” at the 1934 Chicago World’s Fair as a solution to the farm crisis. Ford also stepped up his funding of “chemurgical” (a neologism coined in 1934, combining the Greek words

chemi

, or the art of material transformation, and

ergon

, work) experiments, many of which took place in Greenfield Village’s laboratory, to find new industrial uses for agricultural products. Many of his ideas were harebrained, an industrial version of medieval alchemy. Ford once had a truckload of carrots dumped in front of Greenfield Village’s lab and told its chemists to find useful properties from their pulp. But he did have some significant successes. Iron Mountain chemists figured out how to use wood chips to make artificial leather, while the lab at Greenfield Village developed many new uses for soy meal and soy oil.

There is symmetry at work in what Ford thought he was doing at Dearborn and what he hoped to accomplish on the Tapajós, and the progress of both Greenfield Village and Fordlandia proceeded on remarkably parallel tracks, functioning almost as counterweights to each other in a pendulum clock, counting out the last long stretch of Henry Ford’s long life. Ford’s experience with model towns and village industries in the Upper Peninsula and lower Michigan set the stage for his frustrated Muscle Shoals proposal and then for both Greenfield Village and Fordlandia.