Dog Sense (45 page)

Authors: John Bradshaw

Because so many dogs can no longer perform the full repertoire of canid behavior, it isn't always easy for dogs of different breeds to understand one another when they first meet. By deleting and distorting the wolf's range of signaling structures through breeding, we have messed around with the dog's visual communication system to the point where it just doesn't work as well as it should.

Consider, for example, docked or immobile tails. Some breeds, such as bulldogs, have been bred to have very stiff tails that don't wag particularly easily. In many others, such as spaniels, it's traditional to amputate part or most of the tail, ostensibly to reduce the risk of injury. Docked

tails are harder to see than entire tails, so dogs whose tails have been docked find it more difficult to communicate than dogs whose tails have been left as they should be. In 2008, researchers studied the impact of docking on communication by using a robotic model of a dog whose “tail” could be made to wag by remote control.

8

After setting up the robot in off-leash exercise areas, they noticed that when its tail was wagging other dogs would approach it playfully whereas when the tail was upright and motionless other dogs avoided it. These reactions are consistent with what we already know about the use of the tail in signaling. Then the scientists replaced the long tail with a docked version. When the short-tailed robot was let loose in the park, other dogs approached it warily whether the tail was wagging or notâas if they couldn't make up their minds how they were likely to be received. Although a real dog with a docked tail could probably overcome this shortcoming with other aspects of its body-language, the study clearly shows that tail docking puts dogs at a disadvantage when interacting with their own kind. At the very least, they would feel anxious when encountering one another for the first time; at worst, miscommunication could lead to unintended aggression.

Unreliability of visual signals may well be a reason why dogs are so intent on sniffing one another when they meet. As far as we know, selective breeding has had little or no effect on dogs' abilities to communicate by odor. However, the very instability of odor signals as they are altered by microorganisms means that they have to be continually relearned if a dog is to keep up to date with “who smells like what.” Of course, to do so, dogs have to get close to one another, and in judging whether this is a safe maneuver, each must depend on long-distance, mainly visual signals from the other dog. Thus dogs cannot escape the problems of an unreliable body-language, even in this scenario.

As we know from observing their interactions with humans, however, dogs are very flexible when it comes to learning new signals and cues. This flexibility goes a long way toward explaining why most interactions between dogsâeven those with a limited repertoire of visual signalsâend without incident. Dogs are quick learners and can recall the identities of many other dogs, so they can presumably also learn to make allowances for the inevitable body-language deficiencies in dogs they have met before.

In addition, they can modify, even completely alter, their responses depending upon other information available to them. Who is sending the signal? Have I met him before? If not, have I met a similar dog before, and how did that encounter work out? What else is going on? For example, what is the context for the signal: Is the dog standing over a toy, or are other dogs watching us? It's usually to the receiver's advantage to take all of these factors into account before making his responseâexcept on those rare occasions when the other dog appears to be about to attack, in which case immediate flight is probably a more sensible option. Moreover, each encounter provides more information about the signaler that can be stored away for use on a subsequent occasion. In this sense, dogs' native intelligence has enabled them to compensate, most of the time, for the liberties we have taken with their visual signaling structures.

Selective breeding for appearance is largely a product of the last hundred years; for far longerâprobably since the earliest stages of domesticationâman has been breeding dogs for behavior. This tendency has continued right up to the present day, as dogs' roles continue to become more specialized and demanding. For example, the Guide Dogs for the Blind Association in the UK has developed a strain of golden retriever/Labrador retriever crosses that are particularly suited for guide-dog training. Much of this breeding has fitted dogs to particular working roles, thereby doing a great deal to strengthen the bond between man and dog. But in the contemporary West, where dogs' working roles have diminished, some of the more exaggerated behavioral traitsâsuch as indiscriminate chasing and forceful territorialityâcan be unhelpful for dogs whose primary role is to be companions.

One clear personality difference between breeds lies in the extent to which they enact the predatory behavior of their canid ancestors. Some dogs don't show predatory behavior even when you'd expect them to: Wolves, on seeing a small animal running away from them, would instinctively give chaseâas would many dogs, especially the hunting breeds. Others, especially some of the guarding breeds, seem oddly uninterested. Although training plays a part, these differences between breeds are, at their heart, genetic.

The sheep-guarding breeds are extreme examples of this kind of unresponsiveness. Originating around the Mediterranean, these dogs include the Pyrenean mountain dog, the Italian maremma, the Hungarian kuvasz, and the Turkish karabash and akbash. Many of them are entirely or largely white, bred to look more like sheep and less like wolves. Traditionally, these dogs were raised with livestock and then kept with the flock to guard it against predators. They thus treat members of the flock as part of their own social group, confining their aggression to whatever they perceive as threatening to themselves or their flock. They do attack and kill rabbits, so some of their predator behavior must remain intact. However, they have been reported not to know what to do with their killsâthey simply carry their dead prey around until it falls to pieces. All dogs may be born with the ability to perform the various elements involved in predatory behavior, but in some breeds some of these elements don't appear until adolescence and thus never become integrated into the rest of their behavior.

9

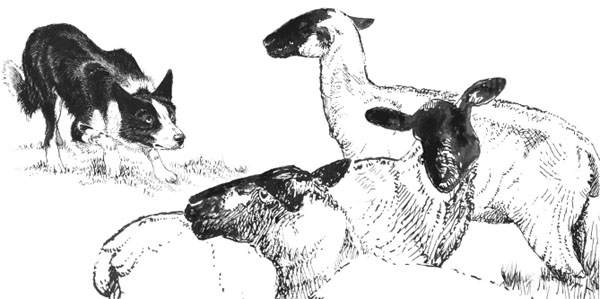

On the other end of the spectrum are working collies, who display a different modification of predatory behaviorâalbeit also for peaceful ends. Hounds and terriers used for hunting will complete the entire wolf hunting sequence right through to consuming their prey, unless they have been trained not to, but this is essentially unreconstructed canid predatory behavior; the aforementioned hunting elements are present, but subtly reorganized in the collie. Herding sheep the collie way involves three key elements of predatory behavior: the “eye” (fixing the gaze, thought to be intimidating), the stalk, and the chase. Collie pups start to perform these behaviors at a very early age and integrate all three into their play. It is then possible for the shepherd to train the young dog to perform each of these separately, on command. The later and most violent parts of the predatory sequenceâbiting and, eventually, killingâare suppressed if necessary by training, although many collies seem to break off naturally after the chase. Herding ability in border collies is surprisingly heritable (in other words, some collies are born better herders than others), indicating some residual variation even within the breed. Thus selection for this crucial ability, while it must have been and probably still is intense, hasn't yet reached completion.

A working collie

Among dogs who do not work, many of the skills for which they were originally bred become redundantâor worseâin their companionship role. Sometimes this redundancy does not appear to present any problem; for example, many of the most popular companion breedsâsuch as spaniels and retrieversâare descended from working animals. But even in these breeds, there has been a tendency for separate “working” and “show” lines to emerge, with most pet animals coming from the latter. This implies that the dogs selected specifically for work may not fit the companion niche as well as they might. The conflict between working traits and the pet owners' requirements can be even more obvious in herding breeds such as border collies and in hunting breeds such as beaglesâboth of which can require far more exercise and stimulation than the average owner is able to give.

In recent years those who regulate dog breeding have taken on more responsibility to inform prospective owners of breeds' working origins and the problems these can cause for an owner who is not prepared to adapt to them. For example, the UK Kennel Club describes the border collie thus: “He needs a lot of exercise, thrives on company and will participate in any activity. He is dedicated to serving man, but is the type of dog who needs to work to be happy and is not content to sit at home by

the hearth all day.”

10

Compare this to the official UK breed standard, which says simply “Temperament: keen, alert, responsive and intelligent. Neither nervous nor aggressive”âimplying to the uninitiated that no collie will become nervous or aggressive, even though some who are denied the active life they crave can become both. (Some references to a breed's drawbacks are more oblique: “There is no better sight than a Beagle pack in full pursuit, their heads down to the scent, their sterns up in rigid order as they concentrate on the chase. This instinct is mimicked in his everyday behaviour in the park: the man with the lead in his hand and no dog in sight owns a Beagle.”)

11

Nevertheless, prospective owners who take the trouble to investigate the behavioral needs of a breed that takes their fancy should nowadays be able to find fairly accurate information.

However, many of the traits that suit dogs to the companion roleâstrength of attachment to people, ability to cope with unexpected changes in their environment, trainability, and so onâappear to vary as much within breeds as they do between breeds. While not denying that some breeds suit only active lifestyles whereas others find it easier to adapt to the demands of modern city life, I hasten to add that it is often not so much a dog's breed as its individual personality that influences how rewarding a pet it will beâand how happy it will be in that role. Breed standards and descriptions can appear to describe a fixed personality (e.g., “Agile, alert . . . Should impress as being active, game and hardy . . . Fearless and gay disposition; assertive but not aggressive”âfrom the UK breed standard for the Cairn terrier

12

), but scientific exploration of canine temperament has shown that this cannot be relied upon.

The most comprehensive study of dog behavior genetics ever conducted was the Bar Harbor project, which started in 1946 and continued until the mid-1960s.

13

At the time, psychologists and biologists held diametrically opposed opinions about whether genetics influenced personality: The biologists maintained that many differences in character between individual animals (and people) were influenced by genes, while most psychologists held that personality was the product of an animal's early experiences. Dog breeds, at that point genetically isolated

from one another for half a century or so, were chosen as the ideal starting point for answering such a question.

Five breeds, and crosses between them, were examined for consistent differences in behavior. The scientists chose small- to medium-sized breeds with reputations for having contrasting behavioral styles: the American cocker spaniel, the African basenji, the Shetland sheepdog, the wire-haired fox terrier, and the beagle. They bred more than 450 puppies, many purebred, but also some who were crosses between two of the chosen breeds. They raised all of them under standard conditions, allowing the effects of any genetic differences to come through. As they grew up, the puppies were given a wide range of behavioral tests. Some of these examined spontaneous behavior, such as play between puppies in each litter and the response to being picked up by a person. Others tested how easy it was to train each dog to perform simple obedience tasks, such as walking to heel. Still others tested cognitive ability, such as how quickly it took each dog to learn to get through a maze or work out how to pull a bowl of food out from under a wire mesh cover.

Surprisingly, when all the results were compiled, breed turned out to be less relevant to personality than had been expected at the outset. Although each breed was found to have some distinctive behavioral characteristics (e.g., the cocker puppies were much less playful than the others), it was the basenjis that stood out from the rest. Although the descriptions in their breed standards said otherwise, the characters of dogs from the four American breeds overlapped a great deal.

14

Only the basenjis, an ancient breed with distinctive “village dog” DNA, were very different in their behavior. Some of this distinctiveness could be traced to a single dominant gene, which manifested as a tendency among basenji puppies to dislike being handled until they were over five weeks old.