Dog Sense (23 page)

Authors: John Bradshaw

Once the young bird has finished learning, persuading it to change its attachment to its mother is almost impossible. It will usually flee from other animalsâa very sensible thing to do, considering that some might want to catch and eat it. The blocking that prevents the young bird from accidentally forgetting its mother and latching onto something else is called “competitive exclusion”: Once a complete picture of the mother has built up, the imprinting process terminates automatically, preventing the bird from accidentally attaching itself to another goose if its mother is temporarily absent.

This “sensitive period” concept explains the behavior of many young animals. For example, it can explain why hand-raised rhesus monkeys, taken from their own mothers soon after birth, prefer to be with their surrogate “mother” rather than with real monkeys, even when the surrogate is only a cloth-covered, unresponsive dummy.

Dogs do this too: They imprint onto their mothers, and

vice versa

, and they do this using their number-one sense: olfaction. In one set of experiments,

3

researchers collected scents from two-year-old dogs by placing cloths in their beds for three consecutive nights. The dogs had all been separated from their mothers since they were twelve weeks old or even younger. Nonetheless, when their mothers were presented with a selection of these cloths, they were much more interested in their offspring's scent than in the scent of unrelated but otherwise similar dogs. Likewise, the young dogs' behavior showed that they recognized their mothers' scents. A second experiment done at the same time showed that two-year-old dogs were able to recognize their littermates by odor

alone, but only if they were currently living with another member of the same litter. This suggests the existence of a “family odor” that reminded each dog of the brother or sister it was currently living with, even though the odor was coming from a dog living in a completely different household. Similar tests given to four- to five-week-old puppies showed that, even at that young age, they had already learned their litter odor. Unexpected abilities such as these serve to remind us that we still have a great deal to learn about how much information dogs get from odors, even those that are completely imperceptible to us.

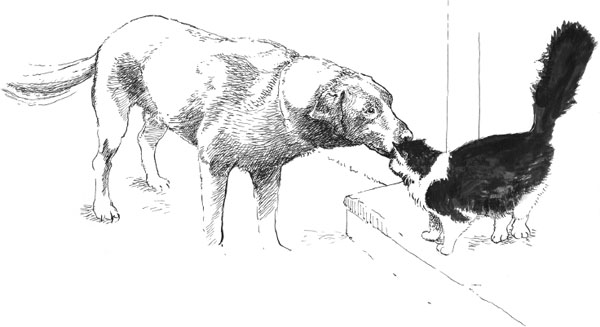

However, the “competitive exclusion” principle doesn't seem to apply to imprinting in the domestic dog. Puppies “imprint” not only onto their own mothers and littermates but also onto people. (Strictly speaking, this phenomenon is slightly different from true imprinting in that it does not seem to be restricted to one individual person, even at the start.) In fact, puppies can also “imprint” onto other animals that they have friendly encounters with during their sensitive period, such as cats. One of the beauties of the capacity for multiple socialization among dogs (and cats) is that they become fearful of one another only if they first meet in adulthood. I have usually kept both dogs and cats at home, and if they're introduced to one another, carefully, when they're young, they can become great friends. The illustration below shows one of my cats, Splodge, performing a tail-up rub, a sign of social bonding, on my Labrador retriever Bruno, while he is wagging his tail in greeting (although I suspect neither understood much of what the other was saying).

Interspecies socialization expressed as species-typical greeting behavior

Sheep-guarding dog with its flock

Some traditional uses of dogs exploit this flexibility. The sheep-guarding breeds, such as the Great Pyrenees and the Anatolian Karabash, if raised with sheep, grow up to behave as if the flock is their family, although of course they behave like dogs rather than like sheep. I say “of course” because dogs' capability to bond to two or even more species at the same time is so obvious that we take it for granted. Such a capacity, however, is highly unusual in the animal kingdom as a whole. Most animals are programmed by evolution to learn about just their own species and no other. Indeed, hand-raised animals often have great difficulty adjusting to living with their own kind, as zookeepers once found, to their dismay, when first trying to breed endangered species of carnivores, especially some of the wild cats.

Domestic dogs don't appear to lose their species identity, even as they form attachments to humans. Not only do they learn about how to interact with other species, but there is no evidence to suggest that this in any way disadvantages them in terms of how they interact with other dogs.

The capacity to adopt multiple identities is unusual, but its origins must lie in regular biological processes. Likewise, since the capacity for interaction with humans can't have sprung from nowhere, its antecedents must lie in the social behavior of the wolf. While I'm highly critical of the old “lupomorph” model when it's applied to social structures, as a biologist my instinct is to look for something pre-existing for evolution to work on. Since dogs are neotenized wolves, it is logical to look for the answer in the behavior of wolf cubs and juveniles rather than in that of adult wolves.

When wolf cubs are born, they are looked after by other wolves. They learn the characteristics of those individuals based on the eminently reasonable assumption that they must be their parents or, in a large pack with existing helpers, their close relatives.

4

When puppies are born, they are usually looked after by both their mother and their owner. Their mother's characteristics are slotted into the “parent” category, simply because she is there and looking after them. This learning will be retained throughout life, forming the basis for one set of social preferencesânamely, for members of their own species (as happens in both wolves and feral dogs). Their owners' characteristics, since they don't match this first category, will be slotted into a second category, generated spontaneously, because they are there and are also caring for them. Apart from this parallel recognition arrangement, there is no reason why everything else about these early social preferences should not be based on the same modelâthat of parent and offspring. Indeed, it is hard to imagine what an alternative model might be.

Put another way, we humans hijack dogs' normal kin recognition mechanisms. The domestic dog puppy's unusual capacity for multiple socialization is the mechanism whereby we can insert ourselves into their social milieu and substitute ourselves into a role that, in the wild, would be served by their parents. Until weaning is complete, the bond with the human owner is probably weaker than with the mother, but after that, attachment to humans is reinforced every day, when we feed our dogs, play games with them, and reward them during training. There are fewer opportunities for pet dogs to reinforce attachments to one another. Even in a multi-dog household, it is the humans who act as the parental figures,

providing food, controlling where the dogs are at any given time of day, and so on. (There are of course a few intentional exceptions to this scenario, such as hunting dogs housed in packs and sled-dogs, whereby leadership from one dog is essential to the coordination of the team.)

Is this really imprinting? Dogs certainly imprint onto their mothers, but science has yet to determine whether they also imprint onto their first owners. Imprinting, in the narrow sense of a bond formed to a primary carer, cannot account for the generally outgoing nature of dogs and, more specifically, for how easy it is for many dogs to change their allegiance from one owner to another. During the early stages of their lives, most mammals learn both the general identity of their species and the specific identities of the individuals around them, especially those that look after them. Normally, the latter characteristic leads to the more powerful attachmentâbut not so in the dog, which shows a much greater flexibility, presumably as a consequence of domestication. However, imprinting, or something very much like it, does play a strong role in directing the dog's preferences for who to approach and who to avoid. These preferences are set up early on in the dog's lifeâspecifically, during the socialization period.

Even though dogs can possess several “friendly” categories simultaneously (a capacity unusual among mammals), each individual has its boundaries. This is well exemplified by some dogs' distrust of children. How do dogs know that children are little humans and not another species entirely? The answer appears to be that they don't. Children

are

distinctly different from adult humans in a number of respectsâthe way they move, the sounds they make, andâprobably of particular significance to dogsâthe way they smell. Dogs that were never exposed to children during puppyhood can be very wary of them when they first meet them as adults, although, being dogs, they can easily be trained to overcome this initial reluctance. On the other hand, if their first encounter with a child involves the pulling of their tail and ears, such dogs can easily become irritable and snappy with other children. The dog

generalizes

between children, treating them as a category rather than as individuals. In the same way, during socialization, puppies must generalize

between one adult human and another. Although puppies undoubtedly come to recognize some people as individuals, unfamiliar people are presumably categorized as “friendly” based on their similarity to the first few people the puppy has met.

This is why it is so important to (gently) introduce puppies to as wide a selection of people as possible: men as well as women (people wearing different kinds of clothes), men with beards as well as clean-shaven men, and so on.

5

This process serves to expand the boundaries of what the dog categorizes as “adult human.” If the template is left too narrow, perhaps because the puppy meets only one or two kennel-maids during the whole of its sensitive period, it may react to the appearance of men with fear and anxiety. This is one of the (several) reasons why owners have difficulties with dogs from puppy farms and pet shops: The puppies' concept of what the human race looks like is often too narrow, and they default to fearful avoidance of every other two-legged animal they meet.

As we have seen, the organization of the dog's social brain is different from that of most other mammals. It can form multiple, on-demand, representational spaces for each of the species that the puppy encounters during the socialization period. This capacity may have a parallel in the way that young children learn languages. Many children around the worldâthough not so many in the United Kingdom or the United States as elsewhereâgrow up hearing two or more languages spoken, and their brains adapt quite well to this circumstance: Each language seems to be stored separately, such that the child quickly becomes competent at not mixing them up when forming sentences. The change in the dog's social brain may have been a product of domestication; alternatively, it may have arisen as a pre-adaptation to domestication in certain wolves that no longer exist in the wild today. Regardless, any dog that only meets other dogs until it is fourteen weeks old develops only one such spaceâdefined initially by its littermates and mother, because they are all that is available, but potentially extendable to all types of dog a little later on in its life. The evidence suggests that a dog born in a human household develops two such spaces, one for dogs and one for humans (again, each with the capacity to expand to accommodate other types of dog, and other types of human, that don't respectively look/sound/smell like the owner's family). A dog born into a human

household also containing a dog-friendly cat may develop three such spaces. And it's possible that dogs born into households with small children develop yet another spaceâor perhaps they learn to generalize between adult and infant humans and thus essentially conceive of them as part of the same continuum of two-legged animals.

In short, dogs have very unusual brains, which allow them to construct several social milieus simultaneously. It is this capacity that enables them to be so useful to us; to cite just two examples, hunting dogs can run in a pack, and sled-dogs can run in a race while remaining under the control of their human handlers. Dogs are born with the potential to develop multiple identities, but all of the detail and context has to be provided by experience. One might argue that this is the only way that domestication could have been made to work. Evolution does not possess foresight, so it could not have provided built-in knowledge of what humans are and how they function in advance; the best that natural selection is likely to be able to provide is the machinery to acquire this knowledge. Socialization to other dogs, on the other hand, is most likely based on mechanisms set up in the early evolution of the carnivores, millions of years before domestication, and may therefore involve some additional processes.