Dog Sense (14 page)

Authors: John Bradshaw

Clearly, dogs' easy sociability requires further examination. Inasmuch as we really don't have access to the world of the ancient, tameable wolves from whom dogs are descended, perhaps it would be best to set aside the origins of the dog altogether. Put simply, the question could be: How would dogs organize their lives if they had the choice, away from mankind's interference? Of course, this is not an easy question to answer because there are very few dogs who live free from human supervision. Dogs rarely survive for long far from human settlements, not least because domestication has all but destroyed their ability to hunt successfully. Although some elements of hunting behavior have been retained in some working breeds, few dogs, if any, possess the innate ability to put all these elements together in order to locate, hunt, kill, and consume prey on a regular basisâand certainly not when competing with other predators.

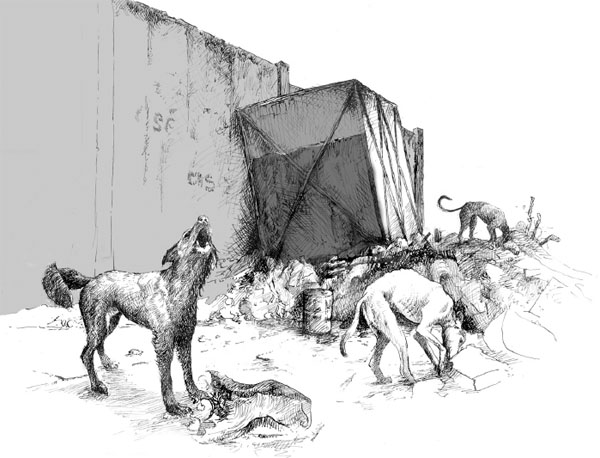

Although it is rare to find dogs who are not controlled by humans, there are enough of them for us to begin forming a picture of what a dog-run society might look like. All over the world there are millions of dogs, generically referred to as ferals or “village dogs,” that are just outside man's direct control. They live on the fringes of human society, scavenging from garbage dumps and begging for handouts, but they are otherwise independent of people and certainly show no allegiance to any human owner. Such dogs are commonplace in the tropics and subtropics: They go by different names, such as the pariah or pye dogs of India, the Canaan dog from Israel, the Carolina dog from the southeastern United States, and the basenji-like village dogs of Africa. Their DNA suggests that many are indeed native to their areas. (By contrast, that of dogs from tropical America suggests descent from escaped purebred European dogs.) There are also a number of ancient types unique to a particular location, such as the New Guinea singing dog, the kintamani from Bali, and the Australian dingoâthe only completely wild dog known to have originally descended from domestic dogs.

Because of its uniqueness, the dingo's story offers a tantalizing example of the social systems that dogs form when left to their own devices. Sometime between five thousand and thirty-five hundred years ago, a single, pregnant domestic bitchâprobably descended from the medium-sized dogs that originally evolved from wolves in Asiaâarrived on the

Cape York peninsula, the northernmost tip of mainland Australia, and escaped into the bush; later, her offspring were joined by a few others, transported by traders across the Torres Strait from New Guinea, as she must herself have been. On arrival in Australia, these escaped dogs found little competition from local (marsupial) carnivores and rapidly became the dominant predator. They were thus able to, and still do, adopt numerous different types of canid social structure; many individuals remain solitary outside of the breeding season, while others form packs of up to a dozen individuals.

Urban scavengers

Although their re-adaptation to the wild offers a compelling glimpse of how dogs might organize themselves in the absence of human intervention, the dingo is a problematic case study. The social behavior of dingoes has been studied in detail only in captivity, where they maintain a pack structure in which sometimes only one pair breeds. As with wolves, this restriction of breeding could be an artifact of captivity, and of the enforced mixing of unrelated individuals. Moreover, dingoes have experienced several thousand generations of living in the wildâa long

enough period in which to become undomesticated, to lose the characteristic behaviors of their village dog forebears. What we know of the dingo is therefore not ideal for understanding how domestic dogs would organize themselves if they were allowed to do so unconstrained by captivity. Better would be studies of dogs that have not reverted to the wild so comprehensively.

Until about ten years ago, the few studies of ferals or “village dogs” that had been published painted a misleading picture of their social organization. Their groupings appeared to be mere aggregations, with little coordination of activity. No compelling evidence was found for cooperative behavior within feral dog “packs.” Instead, researchers witnessed dogs fighting over food that could not easily be shared. Similarly, pregnant females would leave their packs to have their young, returning only when those puppies could stand up for themselves, and males played no part in looking after the young.

The reason that these early studies of feral dogs revealed such competitive social “systems” was, with a dash of hindsight, obvious: Most of the studies had been conducted in Western countries such as the United States, Italy, and Spain, where feral dogs are generally regarded as a nuisance and never allowed to settle anywhere for long enough to develop their own social culture. The “packs” that do form are generally composed of unrelated individuals, with none of the mutual assistance from close kin that benefits the typically interrelated wolf pack. Constantly at risk of being shot, trapped, or poisoned, and prevented from accessing their food supplies (e.g., garbage dumps), these dogs probably never have the time to establish permanent relationships with others, let alone develop a culture of cooperative behavior. To flourish, cooperative behavior relies on exactly the right circumstancesâregular interaction with the same individuals, access to sufficient food and consistent shelter, and a structure based on family ties. Only then will a group be sufficiently coherent to act together against other groups without disadvantaging any of its own members. Because of the environments in which these early studies of feral dogs were conducted, they gave no indication as to where the enormous affability of domestic dogs had originated.

In short, a proper understanding of the sociable behavior of domestic dogs required studies of feral dogs that were not persecuted, and so

could form stable groups without a fear of man. Scientists found what they needed in West Bengal,

1

where villagers allow feral dogs to live alongside them, generally tolerating their presence even if the dogs choose to rest just outside a house's front doors. Dogs like those in modern West Bengal appear to be little different from the dogs who lived in the Fertile Crescent of the Near East, where modern civilization is thought to have arisen some ten thousand years ago. Their behavior may therefore be similar to that of some of the earliest domesticated dogs. In addition to scavenging, these “pariah dogs” are occasionally given food. But feeding does not constitute ownership; these are independent animals, living a commensal lifestyle like that of a city pigeon.

Pariah dogs

The independence of West Bengal's pariah dogs, maintained over many generations, gives them every opportunity to demonstrate the dog's natural social structureâsome aspects of which mirror that of wolves. A given town may support several hundred individuals, but the dogs tend to cluster into smaller family groups numbering five to ten members, just like wolves or indeed other canids. Yet they forage singly, since there is no large local prey available that requires communal hunting, and so it's perhaps slightly misleading to refer to such groups as “packs” in the wolf sense. However, they do share a communal territory, which they will defend against the members of neighboring groups. So far, so much like wolves.

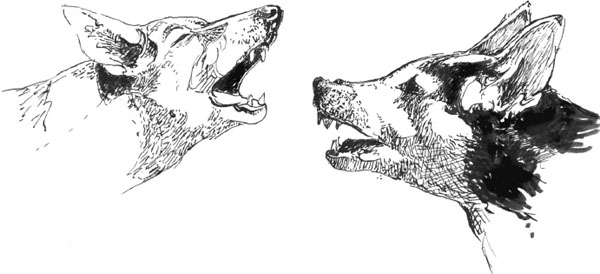

Yet while some aspects of wild dogs' social structures are similar to those of wolves, their sexual and parental behaviors are radically different. Taken as a whole, the reproductive behavior of these feral groups is quite unlike that of the grey wolf and much more like that of other species from the dog family with far less structured social lives, such as the coyote. In a wolf pack, only one male and female will breed; they are conventionally referred to as the “alpha” pair. But when each female pariah dog comes into heat, she is courted by many males, mostly from outside her own pack, with up to eight males fighting for her attention. Although she rejects some, several others may be judged worthy, and she is likely to copulate and “tie” with each, sometimes even more than one on the same day. After mating is over, one of these males will often pair up and stay with her until after the pups are born. Some paired-up males will even go so far as to assist with feeding the litter by regurgitating food for them. Whether the male of a pair is usually the father of all, some, or even

any

of the pups is unclear, so his reasons for investing his time in staying with the female can only be guessed at. Perhaps his hope is that if he helps with this litter, she will give him exclusive mating rights next time. Thus every “pack” of village dogs annually fragments into pairs, each looking after their offspring separately, until they and their adolescent young rejoin the group. When the next mating season arrives, each adult may form a pair different from that of the previous year. In contrast to wolf packs, there is no apparent consistency in the family structure, nor do young adults help their parents in raising the next year's litter.

Pariah dog packs are, in many ways, quite unlike wild wolf packsânor do they resemble the artificial wolf packs that are often assembled in zoos. Many groups contain several adult females, and they are usually tolerant of one another, even in the mating season. Unlike captive wolves, none seems to want to monopolize the best of the males or to prevent others from breeding. Wolf-like ritualized indicators of dominance or submission are apparently never used by either males or females, although the dogs do seem to recognize one anotherâan ability essential to maintaining a group's cohesionâand regularly exchange what appear to be subtle greeting signals. However, there does seem to be some sort of hierarchy; the oldest breeding pair is the most aggressive,

especially toward any unpaired males. Possibly the male of the pair sees these unpaired males as potential future rivals, while the female may be concerned for the safety of her pups.

A further striking difference is that neighboring groups of pariah dogs seem to be able to coexist amicably, whereas adjacent wolf packs try to avoid one another whenever possibleâand when they do meet, they almost always fight. Although aggression between members of different groups of West Bengal feral dogs does occur from time to time, in many such encounters both dogs defer to each other and then return to their core areas. These dogs do not appear to be motivated by any desire to dominate or displace their neighbors, who must occasionally compete with them for food, even those they are presumably sure are unrelated to them. In short, the highly competitive nature of unrelated wolves seems to have been completely erased from feral dogs.

The West Bengal studies tell us a great deal about the way that dogs might prefer to organize their lives. They do not seem to be able to adopt the “family pack” structure that is typical of the wolf. Although they do form bonds with family members, these bonds are far looser than among wolves; more important are the bonds between mother (and to some extent father) and the dependent young. As they grow to adulthood, the young share territory with their parents but do not help them raise their younger brothers and sisters. While dominance hierarchies are evident, they predict only which dogs get priority of access to food and shelter, not who breeds successfully. Thus despite the comparatively crowded conditions in which feral dogs live, they do not behave any more like captive wolves than like wild wolves. There is not the slightest shred of evidence that they are constantly motivated to assume leadership of the pack within which they live, as the old-fashioned wolf-pack theory would have it.

The affability of dogs who are not related to each other and are not part of the same pack must have been a necessary component of domestication. For instance, domestic dogs live much more closely with one another than wolves doâa characteristic that must be a product of their adaptation to exploiting a new, more centralized food supply. Large predators such as wolves cannot afford to live at high densities, because they

would never be able to find enough food. Thus wolf packs rarely have more than twenty or so members, and they defend very large territories. The dogs that accompanied hunter-gatherers, only recently domesticated from wolves, may have been equally intolerant. However, as soon as humans began to live in large permanent villages, dogs would have needed to evolve ways of coexisting with unrelated animals, the debilitating alternative being constant wariness and frequent fights. Although they exhibit this very characteristic today, and therefore illuminate the domestication process, the situation of the pariah dogs is, needless to say, a long way removed from that of a pet dog living in a typical household. Indeed, pet dogs are usually neutered, and even dogs kept primarily for breeding are not generally allowed to form long-term pair-bonds with the partner of their choice.